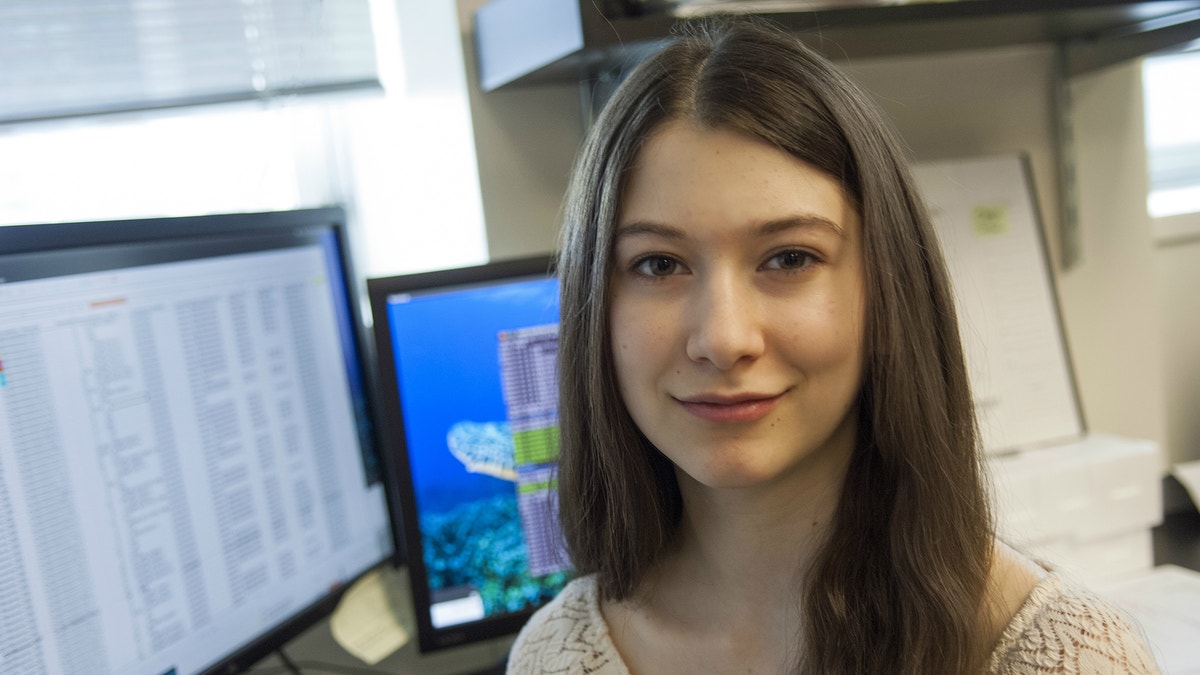

This handout photo shows Elana Simon, 18, of New York, pictured in a laboratory at The Rockefeller University in New York. The teen survivor of a rare liver cancer spearheaded a study, published Thursday in the journal Science, that led a team of researchers to find a gene flaw involved with the disease. (AP Photo/Zach Veilleux, The Rockefeller University)

First the teenager survived a rare cancer. Then she wanted to study it, spurring a study that helped scientists find a weird gene flaw that might play a role in how the tumor strikes.

Age 18 is pretty young to be listed as an author of a study in the prestigious journal Science. But the industrious high school student's efforts are bringing new attention to this mysterious disease.

"It's crazy that I've been able to do this," said Elana Simon of New York City, describing her idea to study the extremely rare form of liver cancer that mostly hits adolescents and young adults.

Making that idea work required a lot of help from real scientists: Her father, who runs a cellular biophysics lab at the Rockefeller University; her surgeon at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; and gene specialists at the New York Genome Center. A second survivor of this cancer, who the journal said didn't want to be identified, also co-authored the study.

Together, the team reported Thursday that they uncovered an oddity: A break in genetic material that left the "head" of one gene fused to the "body" of another. That results in an abnormal protein that forms inside the tumors but not in normal liver tissue, suggesting it might fuel cancer growth, the researchers wrote. They've found the evidence in all 15 of the tumors tested so far.

It's a small study, and more research is needed to see what this gene flaw really does, cautioned Dr. Sanford Simon, the teen's father and the study's senior author.

But the teen-spurred project has grown into work to get more patients involved in scientific research. Scientists at the National Institutes of Health are advising the Simons on how to set up a patient registry, and NIH's Office of Rare Diseases Research has posted on its web site a YouTube video in which Elana Simon and a fellow survivor explain why to get involved.

"Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Not easy to pronounce. Not easily understood," it says.

Simon was diagnosed at age 12. Surgery is the only effective treatment, and her tumor was caught in time that it worked. But there are few options if the cancer spreads, and Simon knows other patients who weren't so lucky.

A high school internship during her sophomore year let Simon use her computer science skills to help researchers sort data on genetic mutations in a laboratory studying another type of cancer.

Simon wondered, why not try the same approach with the liver cancer she'd survived?

The hurdle: Finding enough tumors to test. Only about 200 people a year worldwide are diagnosed, according to the Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation, which helped fund the new study. There was no registry that kept tissue samples after surgery.

But Simon's pediatric cancer surgeon, Sloan-Kettering's Dr. Michael LaQuaglia, agreed to help, and Simon spread the word to patient groups. Finally, samples trickled in, and Sanford Simon said his daughter was back on the computer helping to analyze what was different in the tumor cells.

At the collaborating New York Genome Center, which genetically mapped the samples, co-author Nicolas Robine said a program called FusionCatcher ultimately zeroed in on the weird mutation.

Sanford Simon said other researchers then conducted laboratory experiments to show the abnormal protein really is active inside tumor cells.

He calls it "an exciting time for kids to go into science," because there's so much they can research via computer.

As for Elana Simon, she plans to study computer science at Harvard next fall.