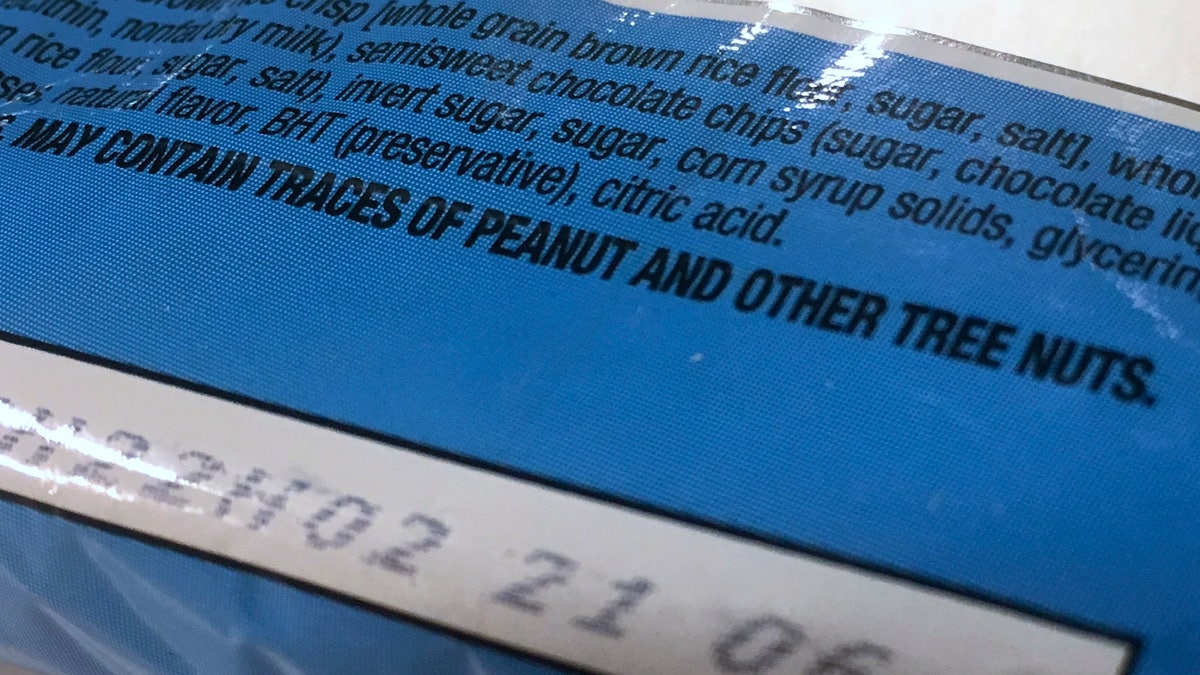

This Nov. 30, 2016, photo shows part of a food label that states the product "may contain traces of peanut and other tree nuts" as photographed in Washington. A new report says the hodgepodge of warnings that a food might accidentally contain a troublesome ingredient is confusing to people with food allergies, and calls for a makeover. The report from the prestigious National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine said it's time for regulators and the food industry to clear consumer confusion with labels that better reflect the level of risk. (AP Photo/Jon Elswick)

"Made in the same factory as peanuts." ''May contain traces of tree nuts." A new report says the hodgepodge of warnings that a food might accidentally contain a troublesome ingredient is confusing to people with food allergies, and calls for a makeover.

Foods made with allergy-prone ingredients such as peanuts or eggs must be labeled so consumers with food allergies know to avoid them. But what if a sugar cookie picks up peanut butter from an improperly cleaned factory mixer?

Today's precautionary labels about accidental contamination are voluntary, meaning there's no way to know if foods that don't bear them should — or if wording such as "may contain traces" signals a bigger threat than other warnings.

Wednesday, a report from the prestigious National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine said it's time for regulators and the food industry to clear consumer confusion with labels that better reflect the level of risk.

Today, "there's not any real way for allergic consumers to evaluate risk," said National Academies committee member Stephen Taylor, a University of Nebraska food scientist. He said research raises concern that consumers might simply ignore the precautions, "essentially a form of playing Russian roulette with your food."

Food allergies are common and sometimes can trigger reactions severe enough to kill. About 12 million Americans have long been estimated to have food allergies, and scientists question if they're on the rise.

But Wednesday's National Academies report found that while food allergies are a serious public health problem, no one knows exactly how many people are affected — because that hasn't been properly studied, in either children or adults. The report urged government researchers to rapidly find out, a key first step in learning whether allergies really are increasing and who's most likely to suffer.

The panel also recommended:

—Better informing new parents about allergy prevention. Recent research has found that introducing potential allergy-triggering foods such as peanut butter before age 1 is more likely to protect at-risk children than the old advice to wait to try those foods until tots are older.

—Better education for consumers and health professionals alike about the differences between true food allergies and other disorders that people sometimes misinterpret as allergies, such as lactose intolerance and gluten sensitivity.

—Better training for restaurant workers, first responders and others about helping people avoid foods they're allergic to, and how to treat severe allergic reactions with a quick jab of the drug epinephrine, often sold as an EpiPen.

The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America welcomed the recommendations as a "roadmap" of ways to improve the lives of families with food allergies.

The labeling recommendation, if eventually adopted, could mark a big change in how allergic consumers decide what packaged foods are safe to eat.

The report said the Food and Drug Administration should replace the "precautionary" label approach with one that's risk-based. The idea: Determine a safety level for different allergens — just how much of a "trace" of peanuts or eggs or milk could most people with allergies tolerate? The resulting labeling would give consumers more information in deciding if they'd take a chance on a food or not, said Taylor, who pointed to a similar voluntary system in Australia and New Zealand.

A food industry group indicated support.

"Our members are committed to ensuring that food allergic consumers have the information they need on the food label to make informed choices about the safety of the products they purchase. We support the recommendations of the National Academies to establish threshold limits for products that use a 'may contain' allergen precautionary statement," the Grocery Manufacturers Association said in a statement.

FDA spokeswoman Megan McSeveney said the agency was reviewing the report but was "particularly interested" in the science behind the panel's labeling recommendations.