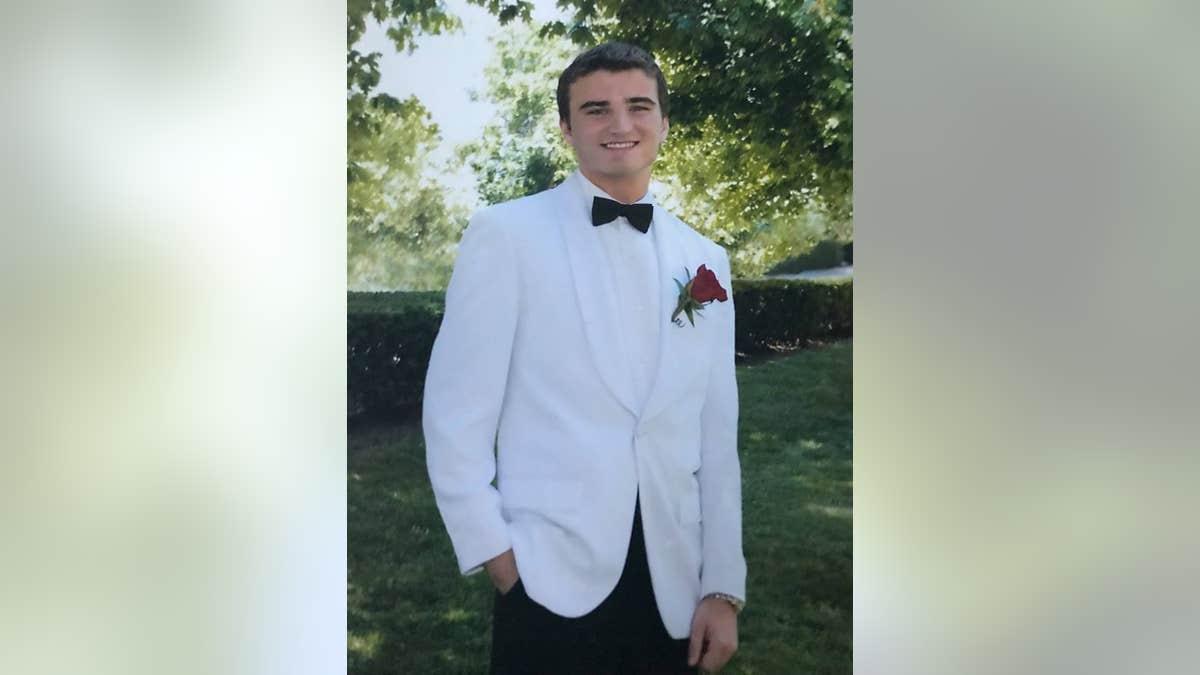

Gage Bellitto, who would have turned 20 on Dec. 25, was a Columbia University transfer looking to study economics. He died alone of a suspected opioid overdose on Dec. 22. (Facebook)

The opioid crisis in America clearly has no borders or boundaries.

Kyle Bellitto, a lawyer, and her husband, Glenn Bellitto, 59, a finance professional — both with Harvard degrees — of the leafy Bronxville, a Westchester suburb in New York where the median household income is $200,000 a year, learned the hard way when their 19-year-old Ivy League son died in December of a suspected opioid overdose, The New York Post reported.

Their son, Gage, who would have turned 20 on Christmas 2017, was a Columbia University transfer looking to study economics. Police have said he apparently died alone on Dec. 22, five days before investigators found his body.

According to the Post, police believe Gage got his opioids — which could have ranged from painkillers to heroin — illegally. His case is still under investigation.

Their son was driven, and from his early teens wanted to follow in the footsteps of his successful family. “He had this list of the best colleges in the U.S. and his goal was to get as high on the list as possible,” Kyle Bellitto told the Post. “When he really set his mind to something, he’d stop at nothing to achieve it.”

Their son, however, had a drug problem — its severity he kept from family, but his friends knew, according to the report.

“We knew he was prescribed things and drank beer and smoked,” his mother said.

“Cocaine was really big for him,” Will Rabsey, 19, who went to all 12 years of elementary, middle and high school with Gage, told the Post. “I remember a few times he’d put a line out and I’d say, ‘Damn, Gage, that’s a lot.’ He’d say, ‘No, no I’ve done this before. I can handle it.’”

When he moved into a dorm last summer at Columbia, his roommates noticed his drug problem.

“He got worse and worse, and his health completely deteriorated,” Miguel Moya, who lived with Gage, said to the Post. He lost weight, and seemed to live on ice cream sandwiches and Coca-Cola.

According to the Post, Gage lied to his psychiatrist to up his prescription of Klonopin, an anti-anxiety pill. He’d also been prescribed Vyvanse, a stimulant, and methylphenidate — commonly known as Ritalin — to treat attention deficit disorder.

“It was way worse than we had ever imagined,” his father said. “It often isn’t what you see that’s deadly. It’s what you don’t see.”