Pacemakers may fail to properly regulate patients' heartbeats near certain appliances and tools that generate electric and magnetic fields, a German study suggests.

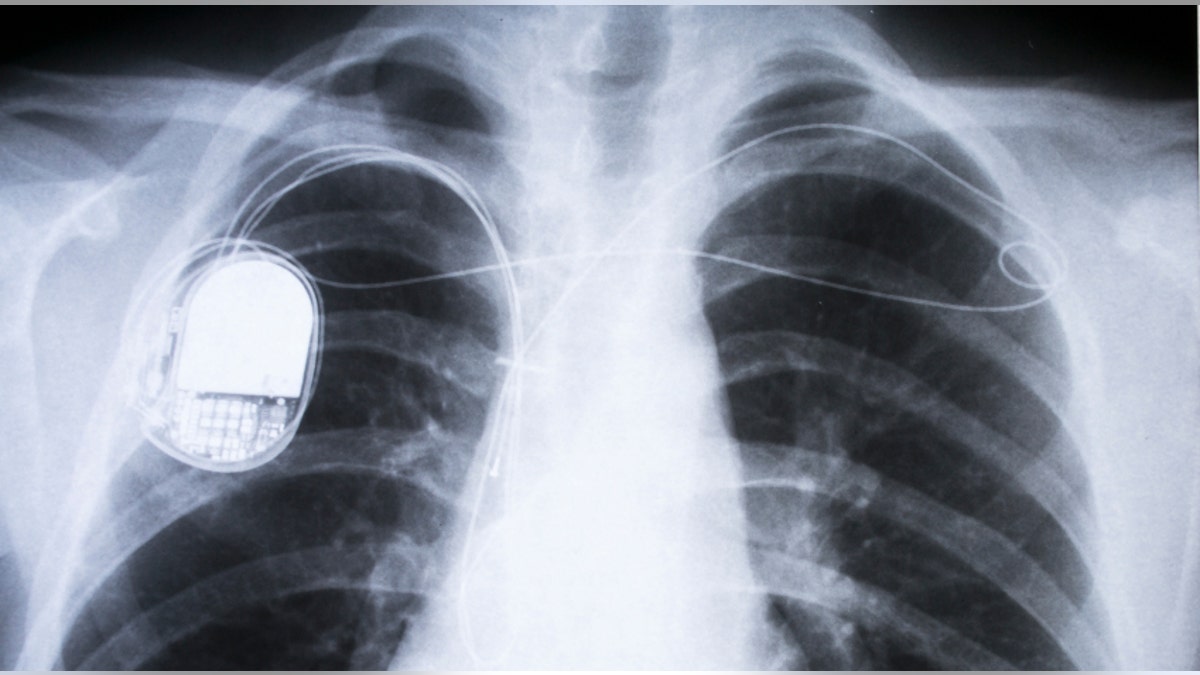

Researchers tested how electric and magnetic fields impact pacemakers, small battery-operated devices that help patients' hearts beat in a regular rhythm, for 119 people under different conditions.

The results suggest that electric and magnetic fields from sources like power lines, household appliances, electrical tools and entertainment systems might interfere with the devices, said lead author Dr. Andreas Napp of the University Hospital Aachen in Germany.

"Usually pacemakers programed to the vendor's recommended settings are safe regarding electromagnetic interference in daily practice," Napp said by email.

"However, lots of electrical appliances from daily life emit strong electromagnetic fields in very close proximity of the appliance," Napp added. "Pacemakers with electromagnetic interference usually show inhibition of stimulating the heart or change the pacing mode or induce a faster heart beat for the time of interference."

For the study, researchers first exposed patients with pacemakers to electrical and magnetic fields similar to frequencies typically used by power grids, 50 Hertz or 60 Hz. Then, they increased the exposure until they detected a pacemaker failure.

Five patients in the study had what's known as unipolar leads, when pacemakers have just one contact point with the heart. The remaining 114 participants had bipolar leads, with two points of contact.

In all five patients with unipolar leads, pacemakers set to either basic or maximum sensitivity were impacted by the initial exposure of 50 Hz, the study found.

For patients with bipolar leads, electromagnetic interference occurred with about 72 percent of cases with maximum sensitivity and 36 percent of instances with nominal sensitivity, researchers report in Circulation.

It's possible that staying more than 12 inches away from an electromagnetic source like an appliance or tool might limit the potential for pacemaker interference, the authors note.

Still, the researchers conclude that people exposed to stronger electromagnetic fields on the job, such as workers in certain types of manufacturing, might need to consider the potential for pacemaker malfunction.

"Patients should inform the doctors before device implantation if they are exposed to strong electromagnetic fields in daily practice or in the work environment," Napp said. "During follow up visits in the pacemaker outpatient clinic, care must be taken while reprogramming the sensitivity of the device."

Welding in particular can expose patients to electromagnetic fields that interfere with pacemakers, said Dr. Gordon Tomaselli, chief of cardiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

"It's not surprising that pacemakers could be coaxed to experience electromagnetic malfunction," Tomaselli, who wasn't involved in the study, said in a phone interview.

Most tools and appliances people use at home probably aren't a problem, Tomaselli added.

"Welders are a problem, but with most other tools people would use I don't prohibit that," Tomaselli said. "But certainly if people are feeling odd or fatigued or having symptoms like they had before they got the pacemaker I tell them to see me or see their doctor."

The study was funded by grants from the German Social Accident Insurance Institution for the Energy, Textile, Electric, and Media Products Sector and the Research Unit for Electropathology.

Dr. Napp and another author, Dr. Matthias Daniel Zink, have both received various forms of support from pacemaker manufacturers.