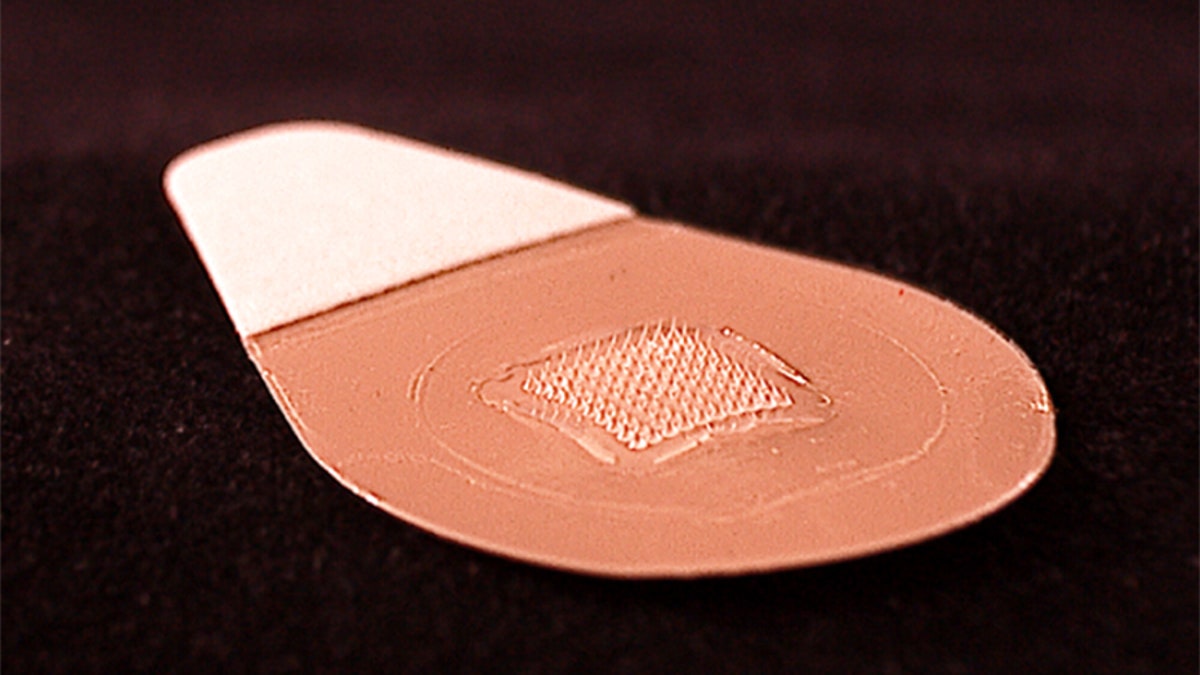

Researchers in Georgia have developed a "microneedle patch" that can deliver the flu vaccine through a person's skin. (Georgia Tech)

Would you be more likely to get your flu vaccine if, instead of getting a shot, you could simply stick a patch on your skin? A small new study suggests that such a patch is safe to use and that people preferred it to a shot.

In the study, which was a phase I clinical trial, the researchers looked at how a "dissolvable microneedle patch" that contained the flu vaccine stacked up against the traditional flu shot . The patch is about the size of a thumbprint and contains 100 needles that are 650 micrometers (or about 0.03 inches) long. Of the 50 participants who tried it, 48 said it didn't hurt.

The researchers found that the microneedle patch was safe and led to a good immune response in the study participants, suggesting that the vaccine was working, although further study of the patch in a larger trial is needed to confirm this. [ Images: The Microneedle Vaccine Patch ]

They also found that the study participants preferred the patch to getting a flu shot, said lead study author Dr. Nadine Rouphael, an infectious-disease specialist and associate professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Georgia.

The finding that the people in the study preferred the patch to the traditional injection was an important one, because not enough people get their flu vaccine each year . The flu is responsible for around 48,000 deaths in U.S. annually, according to the study, published today (June 27) in the journal The Lancet .

The researchers hope that because the microneedle patch is painless and easy to use, "that should encourage more people to get the vaccine," said senior study author Mark Prausnitz, a professor of chemical and biomedical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Prausnitz co-founded Micron Biomedical, a company that manufactures the microneedle patches.

Vaccines via patch

For the most part, medicines are given by one of two methods: a pill or an injection , Prausnitz told Live Science. Most people can take pills, but getting an injection is more complicated and typically requires a trip to the doctor's office, he said.

Prausnitz and his team wanted to come up with a method to make it easier for people to take medicines that normally need to be injected.

The microneedle patch was designed with transdermal patches in mind, Prausnitz said. Transdermal patches are another method of drug delivery, but they only work for a certain subset of drugs that can be absorbed through the skin.

Most medicines are typically not well-absorbed through the skin because of a tough-to-penetrate layer called the stratum corneum, Prausnitz said. But this layer is incredibly thin — about 10 or 20 micrometers thick — which is thinner than a human hair, he said.

In principle, you don't need an inch-long hypodermic needle to puncture a barrier that's thinner than a hair. So Prausnitz and his team went smaller, designing a patch with microneedles loaded with dried flu vaccine. Because the patch uses a dried version of the vaccine, it doesn't need to be refrigerated, and it was shown to be stable in temperatures of up to 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) for up to a year, according to the study.

To apply the patch, a person places it on the back of the wrist and presses down with his or her thumb until a click is heard, Prausnitz said. The click means that you pressed hard enough and can let go. Twenty minutes later — after the microneedles dissolve and vaccine is released into the body — the patch is removed and can be thrown away like a used Band-Aid, he said.

Clinical trial

For the study, in 2015, the researchers recruited 100 adults ages 18 to 49 who didn't receive a flu vaccine for the 2014 to 2015 flu season. [ Flu Shot Facts & Side Effects (Updated for 2016 to 2017) ]

The participants were divided into four groups of 25. Health care workers gave one group the traditional flu shot, the second group the microneedle vaccine patch and the third group a placebo microneedle patch, according to the study. The people in the fourth group put the microneedle patch on themselves after watching a short, instructional video.

The patch appeared to work just as well for the people in the group who put the patch on themselves as it did for the people in the group who had the patch applied by health care workers. After the patch was removed, the researchers measured how much of the vaccine remained in the patch and found no differences between the two groups, suggesting that "participants were able to correctly self-administer" the patches, the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that the participants' immune systems response was just as strong in the people who received the patch as those who received the injection, Rouphael told Live Science. And no one in the study who received the vaccine got the flu during the next six months.

Prausnitz added that the participants said applying the patch didn't cause pain, but that they did feel a "tickling or mild tingling sensation."

Both the patch and the injection caused reactions at the application sites in the following days: The patch was more likely to cause itching and redness, and the injection was more likely to cause pain. This type of reaction is normal and can be explained as the body's response to receiving the vaccine, Rouphael said. Because the patch delivered the vaccine to the surface of the skin, the reaction in that case appeared on the surface, she said, whereas the pain from the injection was more of an intramuscular pain, because that's where the drug was delivered. [ 6 Flu Vaccine Myths ]

Four weeks after receiving the microneedle vaccine patch, 70 percent of the participants said that they'd prefer getting their flu vaccine this way, according to the study.

Because the study included only 100 people, the next step is to conduct a much larger trial, both Rouphael and Prausnitz said. In addition, they hope to someday be able to use these microneedle patches to deliver other drugs and vaccines.

Writing in an editorial that was published alongside the new study in The Lancet, Katja Höschler and Maria Zambon, both of Public Health England, said that the "microneedle patches have the potential to become ideal candidates for vaccinations programs, not only in poorly resourced settings, but also for individuals who currently prefer not to get vaccinated." Höschler and Zambon were not involved in the new study.

The patches might be a particularly attractive option for children , they wrote.

Still, more research is needed to explore how effective the microneedle patch-delivered flu vaccine is, Höschler and Zambon wrote.

Originally published on Live Science .