Newark officials insist city water is safe to drink

Environment advocacy group National Resources Defense Council filed suit against the New Jersey city over lead levels in drinking water.

Lead kills.

Lead is an ancient toxin continuing to wreak havoc despite modern knowledge of its danger. In 1977 lead paint was banned in America. Then in 1986 the use of lead pipes was banned.

And yet, Flint happened.

The dangers of lead consumption have been known for decades. Researchers have found that even low levels of lead in the body can cause serious health problems.

Lead serves no purpose in the body, which is why the body does not know how to process it. Unfortunately, lead resembles calcium so the body treats it as such. Calcium is vital to brain function. In the body lead goes where calcium should, leaving the deadly toxin in places like the bones, teeth and brain.

"Lead is a slow-release toxin that can’t be seen, tasted or smelled in drinking water."

Children are especially at risk. Their brains are still developing and lead can cause intellectual disability. Early exposure to lead can have lifelong consequences, but symptoms aren’t always apparent. Lead is a slow-release toxin that can’t be seen, tasted or smelled in drinking water.

Flint wasn’t the only place bludgeoned by lead. As the crisis roiled, concerns were raised nationwide about the safety of America’s drinking water. That concern embroiled one of the largest cities in New Jersey.

According to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) Drinking Water Watch database, 20 out of 24 samples taken from the City of Newark have already exceeded the federal action level of 15 parts per billion for the current monitoring period. The current monitoring period runs from July 1 to December 31 of this year. Though the period has not ended, one sample provided found 250 parts per billion. That’s 177 percent

higher than the allowable federal lead level.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) both agree that in fact there is no known safe level of lead. Newark leads New Jersey in the number of lead-poisoned children from all potential sources.

The old industrial city of Newark—a town that no other Newark wanted to be mistaken for has been swept up in an aggressive renaissance. Newly minted eateries line downtown Halsey Street and nearby Military Park has been clean-cut—complete with a working carousel. But in spite of the city spinning and fielding Amazonian offers, the lead furor still washed into the Brick City. In 2016, elevated lead levels were found in Newark schools.

Forget the new Brooklyn—is Newark the new Flint?

“The water in our schools was shut off for over nine months.”

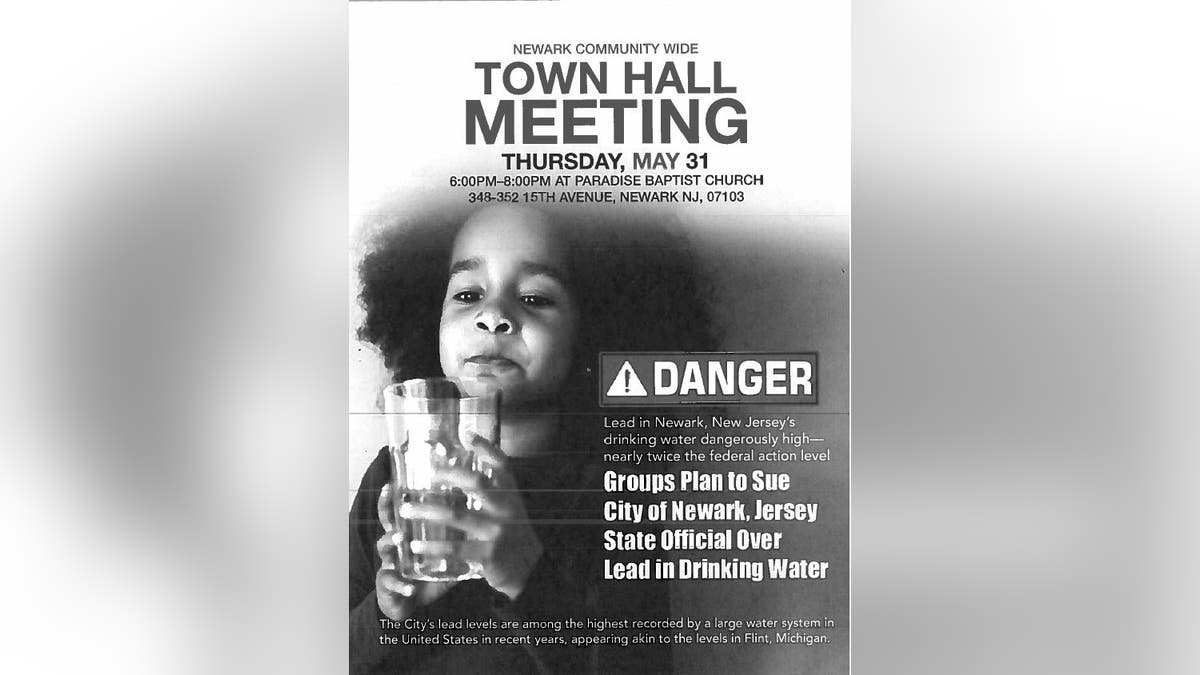

Flint’s exposure of government ineptitude continues to linger. In May, misgivings followed a group into a Newark Baptist church one grey Thursday night. A town hall meeting was scheduled about lead levels in Newark water. Flyers outside the sanctuary showed a girl grasping a glass with an ominous DANGER sign printed beside her. It expressed Newark residents’ unease toward the liquid life force deemed a “death sentence” by some.

A panel discussion unfolded guided by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a group that sued the City of Flint and is now suing the City of Newark and New Jersey state officials for “failure to comply with regulations for the control of lead in drinking water.”

Newark City Hall’s Facebook page actively screams, “NEWARK’S WATER IS ABSOLUTELY SAFE TO DRINK.”

But Flint’s legacy made people doubt.

City officials there told residents the water was safe to drink. In 2018, Flint’s water crisis is still ongoing despite the state of Michigan declaring Flint’s water safe to drink.

“Nobody is drinking water with lead in it.”

NRDC’s lawsuit, filed in June, charges the City of Newark and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) with violating the Safe Drinking Water Act’s Lead and Copper Rule. The rule protects public health by limiting the amount of lead and copper at the tap that is often caused by the corrosion of plumbing fixtures that contain lead and copper. Then the materials enter the water.

Exceeding the limit for lead and copper can make it necessary for corrosion control treatment, which is when a substance is added to water to slow the corrosion of pipes. In the case of Flint, corrosion inhibitors were not added to the water.

As in Flint, NRDC asserts that NJDEP found that the “Newark Water Department is deemed to no longer have optimized corrosion control treatment.”

The Safe Water Drinking Act calls for public water systems to test their water frequently and report the results to their respective states. NRDC says Newark did not conduct the required amount of testing and the testing Newark did conduct produced misleading results. The Lead and Copper Rule says a large water system like Newark’s should be testing a minimum of 100 tap water samples every six months. The majority of those samples should come from high-risk sites classified as Tier 1. NRDC alleges Newark sampled low-risk sites “masking the extent of lead in the City’s drinking water.”

The NRDC lawsuit essentially claims Newark residents have been duped.

Newark activist Donna Jackson says this is a simmering suspicion.

“The water in our schools was shut off for over nine months,” Jackson said at the May town hall meeting. Jackson was referring to 2016 when half of Newark schools had their water fountains turned off due to high lead levels.

Branden Rippey is a teacher at Newark’s Science Park High School as well as a member of Newark Education Workers (NEW) Caucus, a group comprised of members from the Newark Teachers Union, who joined NRDC in the lawsuit against the City of Newark.

At the close of this past school year, Rippey noted there were still a few water fountains turned off.

“In Science, we have water fountains that are connected—one will be on and the other one will be off. That worries me.” Rippey believes the danger lies in the service pipes feeding water into the schools. He does not feel that issue has been properly addressed.

Valerie Wilson, school business administrator for Newark Public Schools says there are no plans to dig up all the pipes at schools and do full replacements.

“That’s a very extensive and very expensive project to do. I don’t think we’ll ever have funding to do that,” Wilson said.

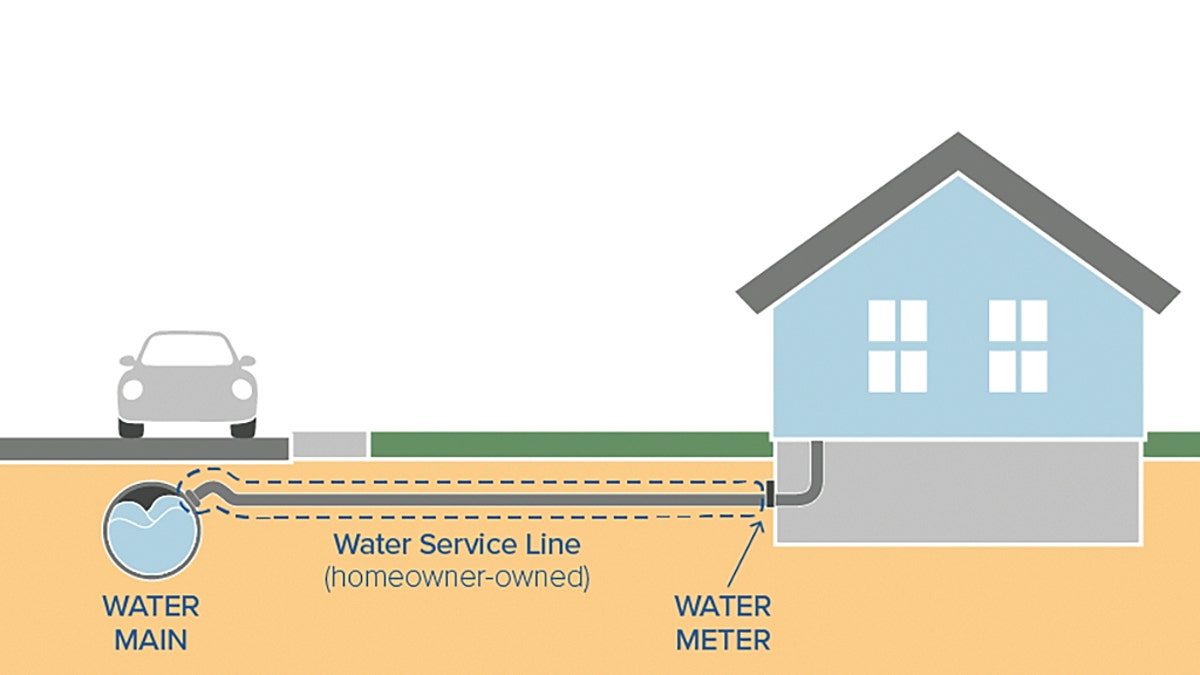

In lieu of an overhaul, the district is performing partial pipe replacements in the 34 schools that need pipes replaced due to elevated lead levels. That is, sections of the water service line are being replaced at the point of school entry. For Wilson, it is a cost-effective measure that she expects to be complete by the start of the new school year in early September.

“Nobody is drinking water with lead in it,” Wilson said. “We have done everything that we can. We’re really at a point where we’re at a long-term temporary fix.”

Though 34 schools were in need of remediation, Wilson says all of Newark’s 67 public schools have had their drinking fountains replaced with updated versions that include EcoWater brand’s Safe Fountain System Model 3000, a water filter.

“Newark is resilient, but we cannot fight something that we are not aware of.”

Teacher Branden Rippey is appreciative of the school district’s recognition of a problem, but he feels the acknowledgement comes a little late and he remains uneasy.

“Our [NEW Caucus] concern isn’t just the schools—it’s the whole city. It hasn’t had good information [on lead] for a few years now,” Rippey said.

NJ.com reported the estimated cost to replace lead service lines in Newark to be $60 million. While the city claims ownership and responsibility over the main water line that runs down a street, property owners are responsible for service lines that connect to it—house to curb. This places significant costs squarely at the feet of Newark residents. However, the city has a Lead Service Line Replacement Program which vows to help reduce the expense.

Newark Department of Water and Sewer Utilities director Andrea Adebowale maintains that Newark water is safe to drink. In a statement provided in June she calls NRDC’s allegation that Newark residents are exposed to dangerous levels of lead “absolutely and outrageously false.” She further states that she is “baffled as to why NRDC makes the innuendo that the Newark water system was responsible for the problem in the schools.” Adebowale says elevated lead levels in schools and homes were caused by pipes and fixtures—not the water system.

(Courtesy: City of Newark)

Those words provide little comfort to Al Moussab, a Newark resident and high school teacher whose daughter was enrolled in Pre-K at one of the tainted schools in 2016. He is also a NEW Caucus member.

“Newark is resilient, but we cannot fight something that we are not aware of,” said Moussab at a June press conference that announced the lawsuit’s filing.

“We need to fight. Water is a basic right. If we’re fighting for just quality water, then there’s a lot of other things that we need to fight for and I think that we have an opportunity within Newark to set an example,” Moussab continued.

While the jury is still out on whether Newark is the “next Flint,” aging infrastructure most certainly guarantees if it’s not Newark, it will be “Anytown, USA.”