(iStock)

Women who have insurance coverage for in vitro fertilization (IVF) may be more likely to have a baby than women who have to pay entirely out-of-pocket for fertility treatments, a U.S. study suggests.

In any given attempt at IVF, insurance status didn't influence whether women had a baby, the study found. But when the first cycle of IVF failed, which often happens, women were more likely to try again if their insurance covered at least some of the costs.

One cycle of IVF can cost around $12,000, with up to another $5,000 for extra medicines women may need, said lead study author Dr. Emily Jungheim of Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine in Missouri.

"Women without coverage for IVF were significantly less likely to try another IVF cycle, likely because the cost was too high," Jungheim said by email. "This wasn't a factor for women with coverage, and as a result they were more likely to have a baby."

A growing number of American women are using fertility treatments to get pregnant, even as the overall birth rate declines. It's become more common as women wait longer to have babies and get married, or avoid marriage altogether, and advances in technology are making more treatment options available.

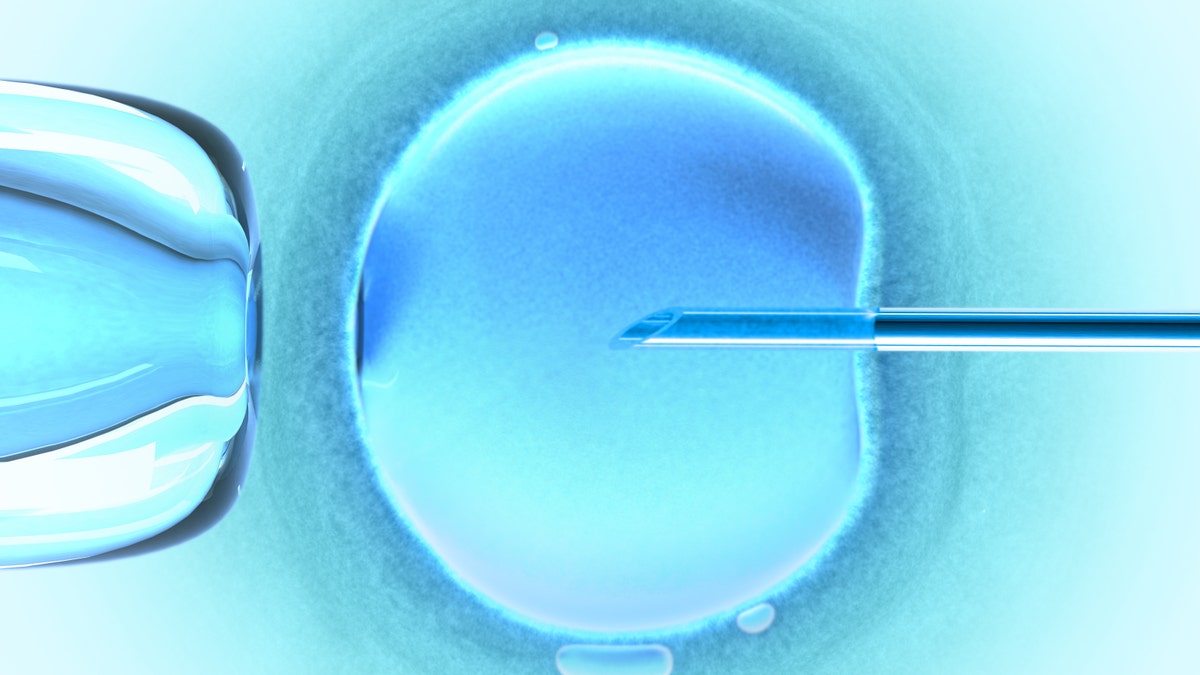

Each year, approximately 1.6 percent of all U.S. babies are conceived using assistive reproductive technology, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IVF is the most common approach. It involves extracting a woman's eggs, fertilizing them in a lab, then transferring embryos into the woman's uterus.

Researchers examined data on 1,572 women seen at Washington University Physicians' Fertility and Reproductive Medicine Center from 2001 to 2010. The center draws patients from Illinois, a state that requires insurers to cover up to four cycles of IVF, and Missouri, which does not mandate IVF coverage.

Overall, 875 women (56 percent) had IVF coverage; 40 percent had state-mandated benefits and 60 percent had benefits without a state requirement. The remaining women lacked coverage and paid for fertility treatments out-of-pocket.

After the first cycle of IVF, 39 percent of women with insurance coverage and 38 percent of women without fertility benefits had a baby, a difference that wasn't statistically meaningful, researchers report in JAMA.

With insurance, 70 percent of women who didn't succeed the first time tried again, compared with 52 percent of women without fertility benefits.

After up to four IVF cycles, the cumulative odds of delivering a baby were better with insurance: 57 percent compared with 51 percent without IVF coverage.

Limitations of the study include the lack of data on women's actual out-of-pocket costs or fertility treatments women might have pursued at other clinics, the authors note.

Still, it's clear that patients with limited financial resources may skip IVF altogether or stop treatment after one or two cycles due to costs, said Judy Stern, an obstetrics researcher at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, New Hampshire who wasn't involved in the study.

"Perhaps because of this, the population doing IVF is already largely a population with higher education and income levels than the general population," Stern said by email. Mandated IVF benefits might expand access, Stern added.

Costs may also push some women to consider implanting more embryos in one IVF cycle, which can increase the odds of pregnancy but also boost the chances of complications like preterm deliveries or fetal growth retardation, said Dr. Kevin Doody, president of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology executive council.

"IVF cycles done in mandated states have fewer embryos transferred at a time because the financial pressure associated with treatment failure results in pressure by the patient to transfer more embryos to increase the chance of pregnancy," Doody said by email.

"This results in an increased risk in multiple pregnancy," Doody added. "The current system where the infertile couple typically bears the cost of IVF, but society at large tends to pay for the consequence of multiple pregnancy is a broken system."