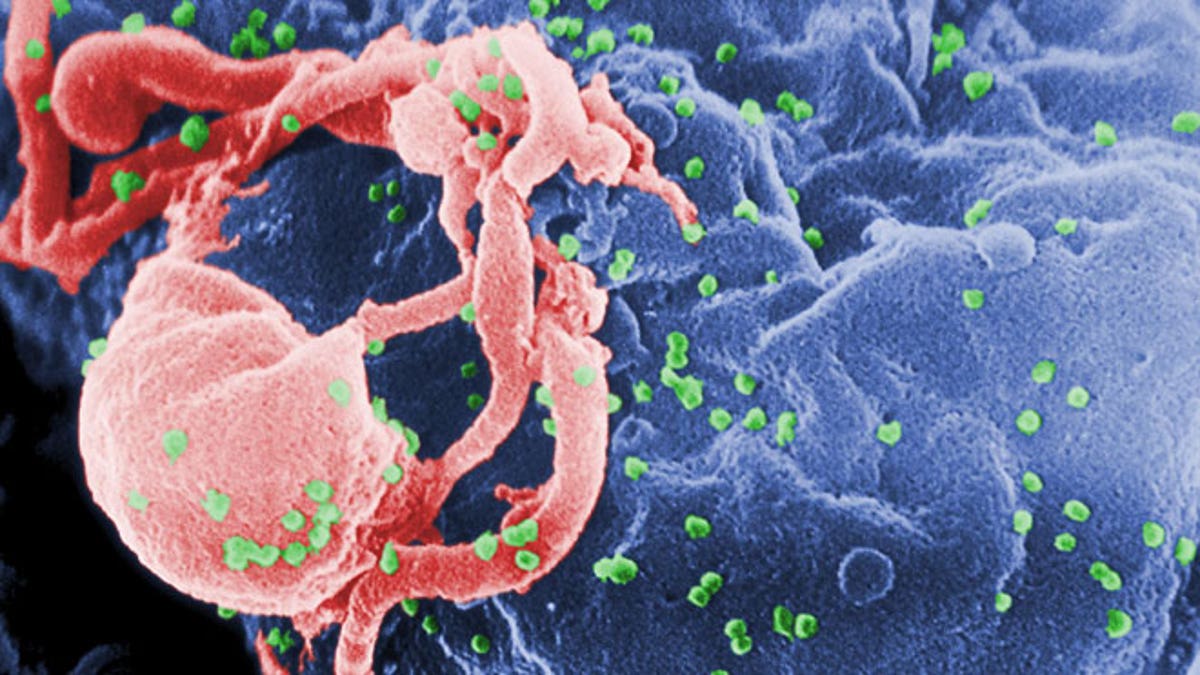

Rapid evolution of HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, is slowing its ability to cause AIDS, according to a study of more than 2,000 women in Africa.

Scientists said the research suggests a less virulent HIV could be one of several factors contributing to a turning of the deadly pandemic, eventually leading to the end of AIDS.

"Overall we are bringing down the ability of HIV to cause AIDS so quickly," Philip Goulder, a professor at Oxford University who led the study, said in a telephone interview.

"But it would be overstating it to say HIV has lost its potency -- it's still a virus you wouldn't want to have."

Some 35 million people currently have HIV and AIDS has killed around 40 million people since it began spreading 30 years ago.

But campaigners noted on Monday that for the first time in the epidemic's history, the annual number of new HIV infections is lower than the number of HIV positive people being added to those receiving treatment, meaning a crucial tipping point has been reached in reducing deaths from AIDS.

Goulder's team conducted their study in Botswana and South Africa -- two countries badly hit by AIDS -- where they enrolled more than 2,000 women with HIV.

First they looked at whether the interaction between the body's natural immune response and HIV leads to the virus becoming less virulent or able to cause disease.

Previous research on HIV has shown that people with a gene known as HLA-B*57 can benefit from a protective effect against HIV and progress more slowly than usual to AIDS.

The scientists found that in Botswana, HIV has evolved to adapt to HLA-B*57 more than in South Africa, so patients no longer benefited from the protective effect. But they also found the cost of this adaptation for HIV is a reduced ability to replicate -- making it less virulent.

The scientists then analyzed the impact on HIV virulence of the wide use of AIDS drugs. Using a mathematical model, they found that treating the sickest HIV patients -- whose immune systems have been weakened by the infection -- accelerates the evolution of variants of HIV with a weaker ability to replicate.

"HIV adaptation to the most effective immune responses we can make against it comes at a significant cost to its ability to replicate," Goulder said. "Anything we can do to increase the pressure on HIV in this way may allow scientists to reduce the destructive power of HIV over time."

The study was published on Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).