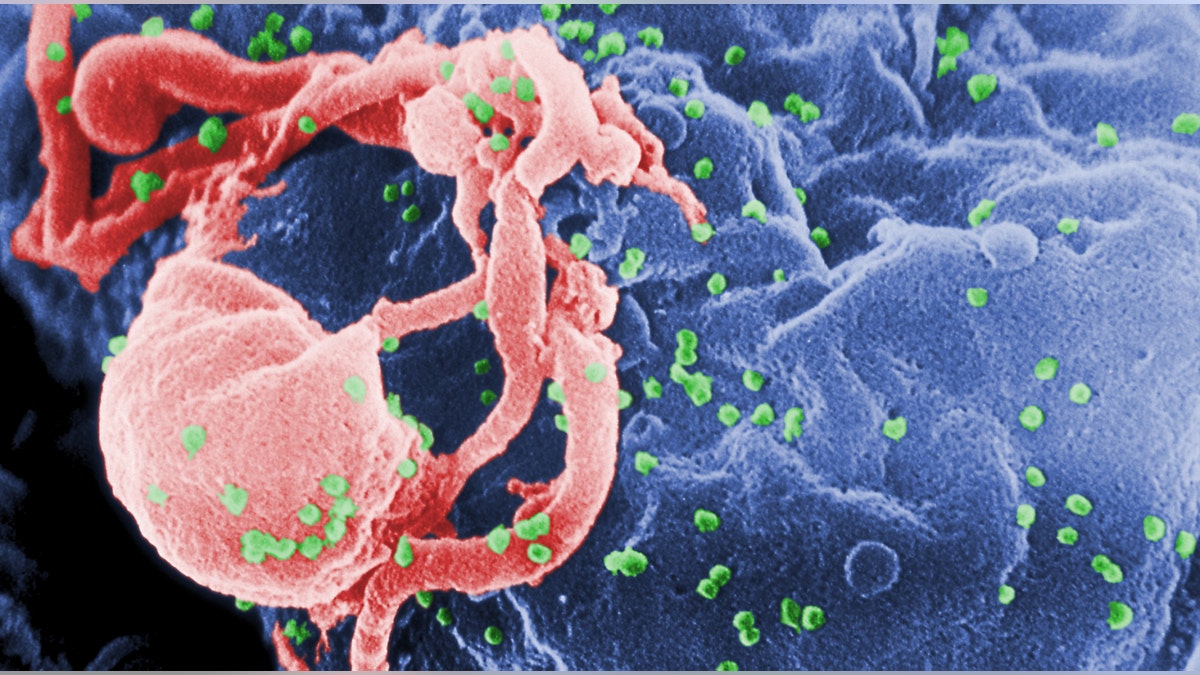

Scanning electron micrograph of HIV-1 budding from cultured lymphocyte. The multiple round bumps on cell surface represent sites of assembly and budding of virions. (CDC.gov)

More than half of gay and bisexual men in the U.S. are not personally concerned about being infected with the human immunodeficiency virus and less than half of men with the virus are being properly treated, according to two new reports.

The data show that significant barriers still exist in the fight against the still-growing epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS, among gay and bisexual men, experts say.

“I think we have the tools at our disposal to arrest the epidemic in the U.S. and clearly these data are very concerning,” said Dr. Kenneth Mayer, an expert on HIV prevention who was not involved in the new reports.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that some 1.1 million people in the U.S. are living with HIV. About one case in six is undiagnozed.

While the CDC says only about 4 percent of U.S. males have sex with other men, they represent about two-thirds of the country’s new infections.

“Among gay men in this country, there is a disconnect about how the epidemic is affecting their community and how they see it,” Jennifer Kates said. “There’s a real knowledge gap.”

Kates is director of global health and HIV policy at The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) in Washington, D.C. , and co-author of a new report on HIV and AIDS in the lives of U.S. gay and bisexual men published by the foundation.

The report found that only a third of respondents knew infection rates were increasing among gay and bisexual men, and more than half weren’t personally worried about becoming infected.

Another recent study found that men at high risk of HIV infection may misjudge their vulnerability (see Reuters Health story of June 26, 2014 here: reut.rs/1sIHfC9).

The CDC recommends routine annual HIV screening for all people ages 13 to 64, and more frequent testing for those at high risk. But less than a third of uninfected respondents to the KFF survey said they were tested for HIV within the past year.

Men younger than 35 were twice as likely to not have been tested for HIV within the past year.

Awareness of how men could protect themselves was also low. Only about a quarter of the KFF survey respondents knew about the daily therapy known as pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP, which may reduce the risk of HIV infection by as much as 92 percent, according to the CDC. The pill currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for PrEP is Gilead’s Truvada.

Kates and her colleagues found as well that less than half of the respondents were aware of current HIV treatment guidelines, which in the U.S. include starting a combination of drugs known as antiretroviral therapy, or ART, as soon as HIV is diagnosed.

The World Health Organization recently changed its recommendations, but it does not fully endorse starting ART at diagnosis.

In a separate report, CDC researchers looked at progress toward getting more HIV-positive men who have sex with men into treatment and keeping their infection at bay. That study found only about three quarters of HIV-positive men received care within three months of their diagnosis.

Additionally, less than half of the respondents to the CDC survey were currently on HIV treatment and only 42 percent had achieved very low levels of the virus in their bodies - known as viral suppression.

“There are data now that if people are on treatment and they are virologically suppressed, they are very unlikely to transmit HIV to partners,” said Mayer, who is co-chair of The Fenway Institute of Fenway Health, which provides healthcare to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community in Boston.

“(PrEP and ART) are very, very effective interventions for combating the epidemic in the U.S. and the fact that this population doesn’t know about them shows we have to get to work on that,” Kates said.

HEALTHCARE, RACE AND STIGMA

Both new reports point to actions, especially by healthcare providers, that can help turn the tide in the U.S. HIV epidemic.

The KFF survey found that over half of respondents said their doctors never recommended HIV tests. Even more respondents said their doctors never or rarely discussed HIV.

“Health providers are part of the problem – definitely,” Mayer said. “It’s not specifically HIV. Healthcare providers are not always comfortable talking to their patients about sex in general.”

He added that healthcare providers may also be uncomfortable discussing certain topics related to HIV, because the majority of them are heterosexuals.

About half of respondents to the KFF survey said they never discussed their sexual orientation with their doctor. About a third said they were uncomfortable discussing topics around sexual behavior with their doctors. Another third said they were only “somewhat comfortable” discussing those topics.

Mayer said resources on The Fenway Institute’s website may help healthcare providers and gay and bisexual individuals during those interactions (bit.ly/1yzB06C).

Both reports also showed significant differences between races in attitudes toward HIV and treatment of the infection.

African Americans and other blacks are most severely affected by HIV, according to the CDC. The agency says one in 16 black men will be diagnosed with HIV during their lifetime if the course of the epidemic doesn’t change.

Yet, the CDC report found that blacks had the lowest level of HIV care, compared to all other races and ethnicities.

More than half of non-white respondents to the KFF survey were personally concerned about becoming infected with HIV, compared to just a quarter of white respondents.

The KFF report also found that non-white respondents wanted more information on how and where to get tested for HIV.

“The impact of the epidemic, they were experiencing that more,” Kates said. “Their concerns were higher.”

Kates said that while barriers to getting HIV tests, prevention and treatment have become lower over the years, they still exist. Additionally, stigma toward HIV continues to be a problem.

“There is still stigma and discrimination and that came through in the survey as well,” she said.

Mayer said one of the keys to addressing the epidemic is to get people to talk about HIV among their friends - straight or gay.

“AIDS is everybody’s problem,” he said. “It’s the job of people who are not gay or at risk to talk about it, too.”

Kates said using the tools available and reaching more gay and bisexual men through education may reduce the men’s risk of coming into contact with the virus.

“I think the opportunity is there to bring the epidemic down to much, much lower levels,” she said.