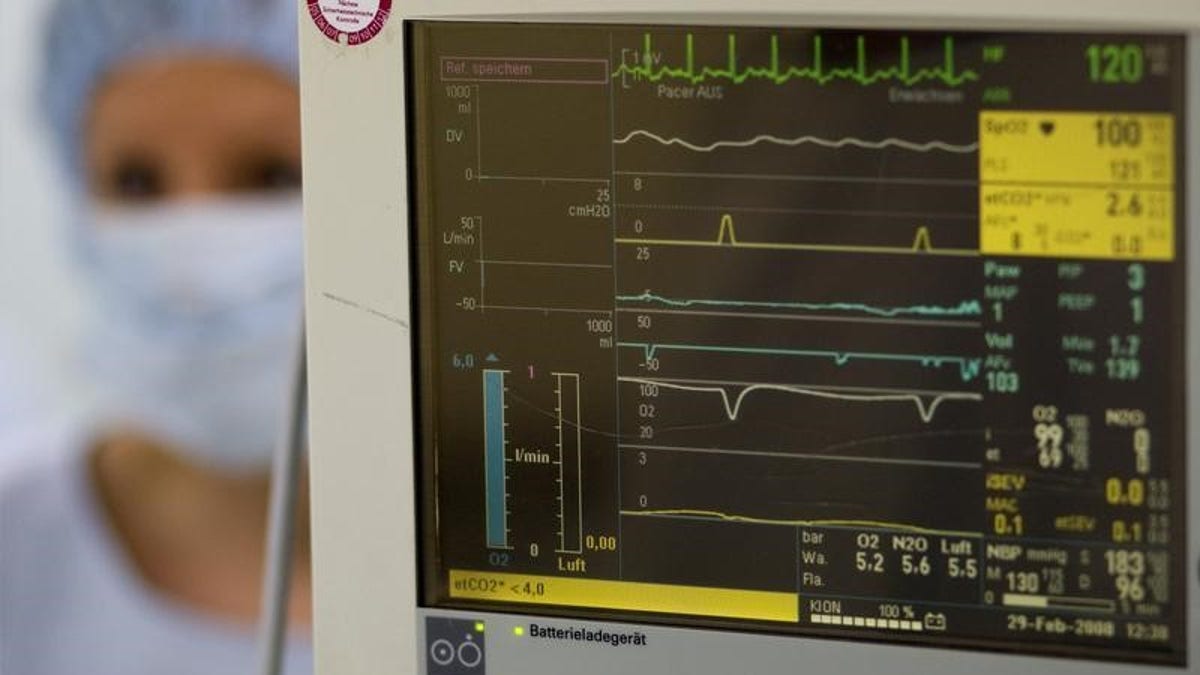

A surgery nurse is seen beside the heart beat monitor in the operating theatre of the Unfallkrankenhaus Berlin (UKB) hospital in Berlin February 29, 2008. REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch (GERMANY) (Copyright Reuters 2015)

Boys with a low resting heart rate during their teen years may be at increased risk for committing violent crimes as adults, a Swedish study suggests.

A low resting heart doesn't necessarily signal a problem. According to the American Heart Association, lower heart rates are common in people who are very athletic, because their heart muscle is in better condition and doesn't need to work as hard to maintain a steady beat.

But previous research has also linked a low resting heart rate to antisocial behavior in children and adolescents, the study authors note in JAMA Psychiatry. A slow heart rate may increase risk-taking, either because the teens seek stimulating experiences or fail to detect danger as much as their peers with normal heart rates, researchers say.

For the current study, a team led by Antti Latvala of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and the University of Helsinki in Finland explored the link between young men's heart rates when they entered military service around age 18 and their odds of later being convicted of crimes as adults.

The study included 710,000 participants born between 1958 and 1991 who were followed for up to 36 years.

Compared with about 140,000 young men with the highest resting heart rates (above 83 beats per minute), those with the lowest heart rates (no more than 60 beats per minute) were 39 percent more likely to be convicted of a violent crime and had a 25 percent higher chance of getting convicted of nonviolent crimes.

"It is obvious that low resting heart rate by itself cannot be used to determine future violent or antisocial behavior," Latvala said by email. "However, it is intriguing that such a simple measure can be used as an indicator of individual differences in psychophysiological processes which make up one small but integral piece of the puzzle."

Researchers are not certain why a slow heart rate might be linked to violence or risk-taking. A low resting heart rate may be an indicator of chronically low physiological arousal - indicating biological underpinnings - and that may cause people to seek stimulating experiences.

Or, Latvala and colleagues write, the low heart rate could be a sign of blunted psychological responses to situations that usually produce stress or anxiety in others, and this might lead to fearless behavior.

Over the course of the study, about 40,000 men were convicted of violent crimes after an average follow up of 18 years. In addition, roughly 104,000 men were convicted of nonviolent crimes after an average follow up of 16 years.

Men who had the lowest resting heart rates during adolescence were also more likely to be killed or injured in assaults or to experience accidents serious enough to merit medical attention or result in death, the study found.

"This is a novel finding and it provides support for a more general association between low heart rate and risk-taking behavior," Latvala said.

The study only focused on men, and the results may not apply to women, the researchers acknowledge. Because the data on crimes was drawn from a registry for convictions, it's also possible that the results might be different for crimes that don't result in convictions.

Even so, the findings raise a host of ethical and legal questions about whether and to what extent the criminal justice system should weigh the potential for low resting heart rate to influence behavior, Adrian Raine, a researcher in criminology and psychology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, noted in an accompanying editorial.

A low resting heart rate can reflect a lack of fear, Raine told Reuters Health by email.

"If you lack fear, you're more likely to commit crime because you're not concerned about getting caught," Raine said. "And, if you're a fearless risk-taker, you're more likely to put yourself in social contexts where you run the risk of violence victimization, and have more accidents due to a reckless disregard for your own safety."

While we might not blame a victim of violence for having a low resting heart rate and ending up in a risky situation, the notion of considering this a mitigating factor in punishing violent criminals is much thornier, Raine added.

The findings also raise questions such as whether car insurance premiums should be higher for people with low resting heart rates, or whether parents of children with low heart rates might seek help before kids grow up to become violent adults, Raine said.

"These findings raise some provocative issues," Raine said.