People may be more likely to get colorectal cancer screenings when doctors let them choose what type of test to have, a U.S. study suggests.

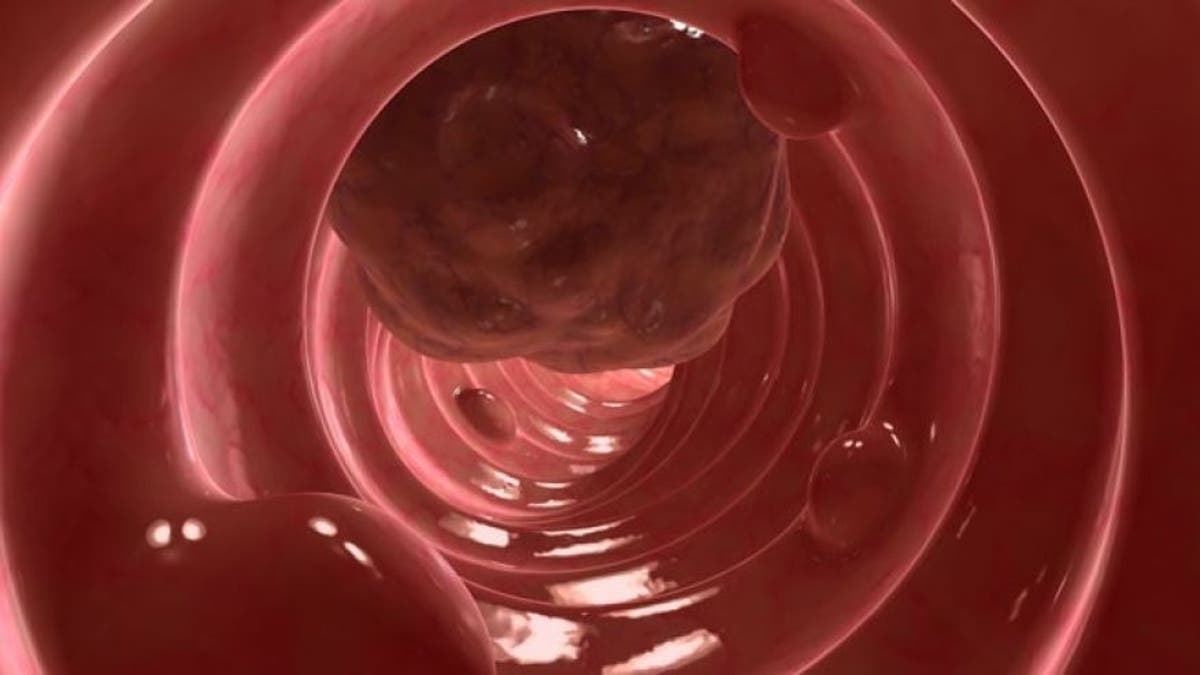

Researchers focused on two widely used screenings. One, a process known as fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), looks for blood - a possible sign of cancer - in stool samples once a year. The other, a colonoscopy exam that snakes a tiny camera through the rectum to view the colon, searches for abnormal growths once a decade.

About 1,000 patients were divided into three groups and randomly assigned to get either FOBT or colonoscopy, or given a choice between the two options.

Over three years, 42 percent of participants given a choice between the tests followed through with screening and 38 percent of people assigned to get colonoscopies did so. Just 14 percent of the patients assigned to FOBT got the test done each year.

In the choice group, there was also a steep drop off in FOBT after the first year among people who had opted for that method.

"Fecal occult blood testing needs to be repeated every year to have the same protective effect as getting a colonoscopy every 10 years," said lead study Dr. Peter Liang of the University of Washington in Seattle. "Allowing people to choose their screening test and using patient navigators to help them get their tests completed will increase the overall adherence to colorectal cancer screening."

To help increase the odds that patients got recommended screenings, members of the research team served as patient navigators during the first year of the study. In this role, they described the screening process to patients, helped schedule tests, explained bowel preparations for testing and helped arrange transportation home after colonoscopies.

Study participants were identified from the San Francisco Community Health Network, a safety net public health system, and there were research team members fluent in English, Spanish, Cantonese and Mandarin.

People who were homosexual, married or in serious relationships were more likely to comply with screenings, as were Chinese speakers, the study found.

Patients who were assigned to colonoscopy or chose this option were considered non-compliant if they failed to get the test within the first year of the study.

Participants who were assigned to FOBT or chose this alternative were counted as non-compliant if they didn't do the test annually during the three-year study, if they did the tests but submitted stool samples incorrectly, or if they failed to follow up with a recommended colonoscopy based on the results.

When researchers looked at whether patients could follow through with FOBT every other year instead of annually, compliance was 40 percent for the FOBT group, 51 percent in the colonoscopy group and 56 percent for the group given a choice between the two options.

U.S. guidelines recommend FOBT every year, but screening programs in Canada and Europe use biannual testing, Liang and colleagues note in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

The study wasn't designed to assess the effectiveness of patient navigators, but one shortcoming of the research was that the withdrawal of this support after the first year might have contributed to lower rates of FOBT compliance, the authors point out.

Even so, the findings highlight the importance of giving patients a say in what type of screening they get, said Dr. Samir Gupta, a researcher at the University of California, San Diego, who wasn't involved in the study.

"Our suspicion is that patients selecting colonoscopy often do so because they value its high sensitivity for polyps and cancer, and don't mind the invasiveness and inconvenience, and that patients selecting stool blood tests often do so because the test is more convenient," Gupta said by email.

While previous research has found lower screening rates in some minority groups, the study findings suggest that language barriers can be overcome with patient navigators, said Dr. David Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

"Suggesting that the patient perform an `unpleasant' test when they have no symptoms requires a strong educational component," Lieberman, who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.