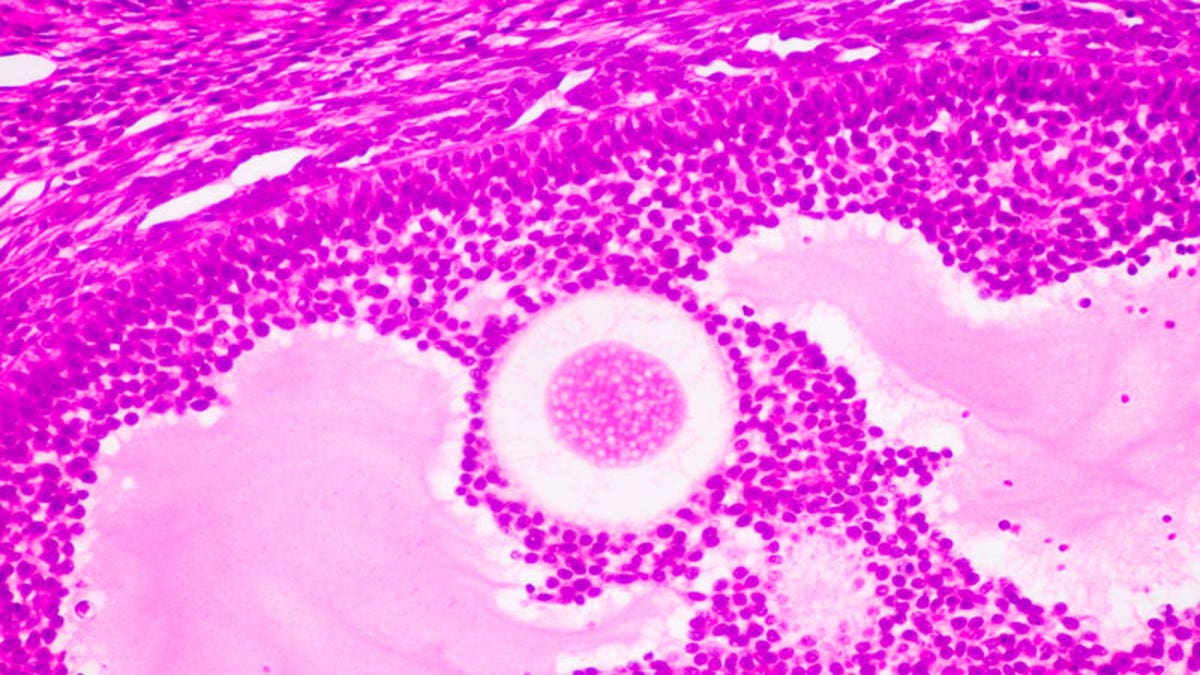

A stock image showing ovary tissue under the microscope.

It's generally thought that women are born with a finite number of egg cells, and cannot grow new ones. But in a new study, researchers got a surprise when they found that women undergoing a particular chemotherapy had a much greater number of eggs in their ovaries than expected.

The reason for the finding isn't clear, but it suggests that the chemotherapy may spur the development of new eggs, the researchers say.

If confirmed, it would be the first time that scientists have seen new egg cells formed in adult women. And understanding exactly how this happens could aid in the development of fertility treatments that allow women to produce more eggs, the researchers said.

However, the researchers caution that the study was small, and the findings do not prove that the chemotherapy treatment caused the production of new eggs. In addition, it's not clear whether the greater number of eggs seen in these women after the chemotherapy treatment would help with their fertility. In fact, another part of the study found that the eggs from these women didn't grow as well in a lab dish, compared to eggs from healthy women.

More From LiveScience

"This study involves only a few patients, but its findings were consistent and its outcome may be significant and far-reaching," study researcher Evelyn Telfer, a professor at the University of Edinburgh's School of Biological Sciences, said in a statement . "We need to know more about how this drug combination acts on the ovaries, and the implications of this."

New eggs?

Women are born with all of the eggs they will use in their lifetimes, but the eggs need to mature inside structures called follicles . Typically, one follicle matures each month, and releases an egg. As women age, the number of follicles in their ovaries declines, which reduces their chances of pregnancy .

Some cancer treatments accelerate the loss of follicles, and thus hurt a women's fertility. But other cancer treatments don't seem to have an effect on fertility.

In the new study, the researchers originally set out to examine why a common chemotherapy treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a cancer of white blood cells) doesn't appear to affect fertility. The treatment is a combination of four chemotherapy drugs — adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine — or ABVD for short.

The researchers analyzed samples of ovarian tissue donated by 8 women who had undergone ABVD, 3 women who had undergone a different type of chemotherapy and 12 healthy women around the same age.

Women who received the ABVD treatment had a much greater number of immature follicles in their ovaries —up to 10 times higher in some cases — than healthy women and those who'd received the other chemotherapy, the study found. Women who'd received ABVD also had a much greater number of follicles than would be expected based on their age.

The follicles in ABVD group also appeared younger — similar to those seen in girls before they go through puberty.

When the researchers tried to grow the follicle in a lab dish, those from the ABVD group didn't grow as well as those from the other two groups - only about 20 percent of follicles from the ABVD group showed growth, compared to 42 to 46 percent in the other two groups, the study found. This limited follicle development is also comparable to what's seen in prepubescent girls, the researchers said.

Future research

The researchers speculate that the ABVD treatment may active stem cells within the ovary to produce new eggs.

"It could be that the harshness of the treatment triggers some kind of shock effect or perturbation which stimulates the stem cells into producing new eggs," Telfer told the Telegraph .

But there could be other explanations, including that the egg follicles were damaged during treatment and split into two or more parts, David Albertini, laboratory director at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York, told the Guardian .

Future studies will examine the effect of each of the four chemotherapy drugs separately, to better understand the mechanism that may be leading to an increased number of follicles, the researchers said.

The study was published online Dec. 5 in the journal Human Reproduction.

Original article on Live Science.