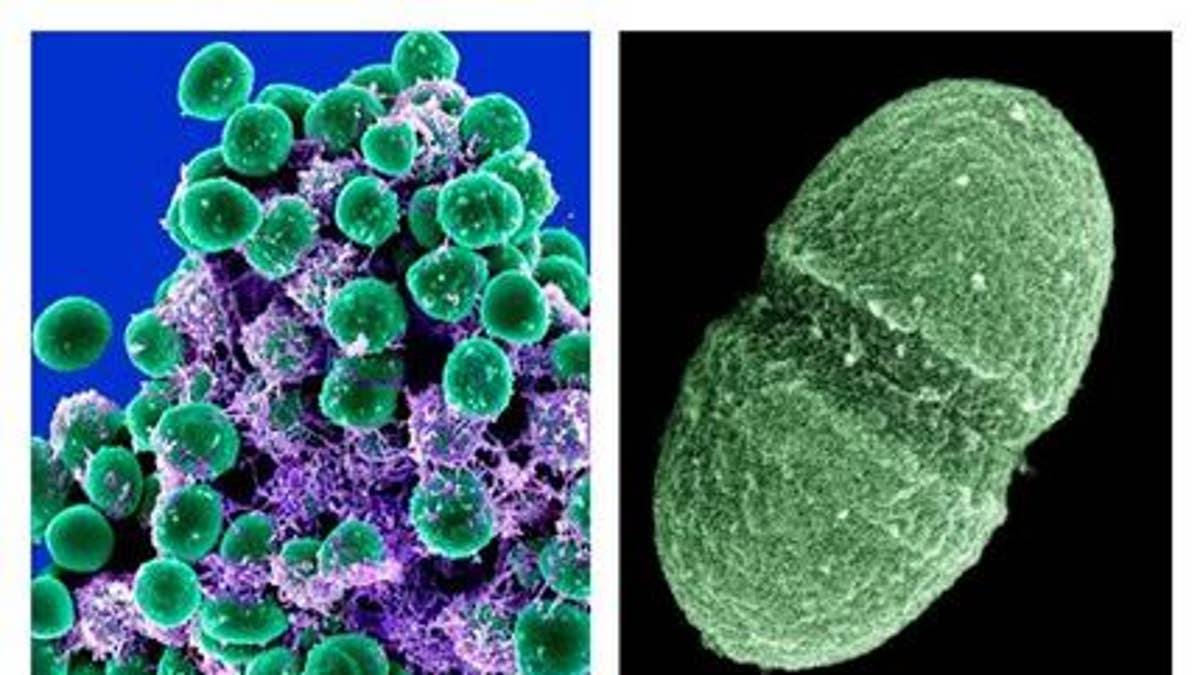

At left, undated handout image provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) shows a clump of Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteria (green). At right, undated handout image provided by the Agriculture Department showing the bacterium, Enterococcus faecalis. (AP Photo/NIAID, Agriculture Department)

They live on your skin, up your nose, in your gut - enough bacteria, fungi and other microbes that collected together could weigh, amazingly, a few pounds.

Now scientists have mapped just which critters normally live in or on us and where, calculating that healthy people can share their bodies with more than 10,000 species of microbes.

Don't say "eeew" just yet. Many of these organisms work to keep humans healthy, and results reported Wednesday from the government's Human Microbiome Project define what's normal in this mysterious netherworld.

One surprise: It turns out that nearly everybody harbors low levels of some harmful types of bacteria, pathogens that are known for causing specific infections. But when a person is healthy - like the 242 U.S. adults who volunteered to be tested for the project - those bugs simply quietly coexist with benign or helpful microbes, perhaps kept in check by them.

The next step is to explore what doctors really want to know: Why do the bad bugs harm some people and not others? What changes a person's microbial zoo that puts them at risk for diseases ranging from infections to irritable bowel syndrome to psoriasis?

Already the findings are reshaping scientists' views of how people stay healthy, or not.

"This is a whole new way of looking at human biology and human disease, and it's awe-inspiring," said Dr. Phillip Tarr of Washington University at St. Louis, one of the lead researchers in the $173 million project, funded by the National Institutes of Health.

"These bacteria are not passengers," Tarr stressed. "They are metabolically active. As a community, we now have to reckon with them like we have to reckon with the ecosystem in a forest or a body of water."

And like environmental ecosystems, your microbial make-up varies by body part. Consider your underarm a rainforest.

Scientists have long known that the human body coexists with trillions of germs, what they call the microbiome. But they didn't know which microbes lived where in healthy people, and what they actually do. Some 200 scientists from 80 research institutions worked together for five years on this first-ever census to begin answering those questions. The results were published Wednesday in a series of reports in the journals Nature and the Public Library of Science.