(AP)

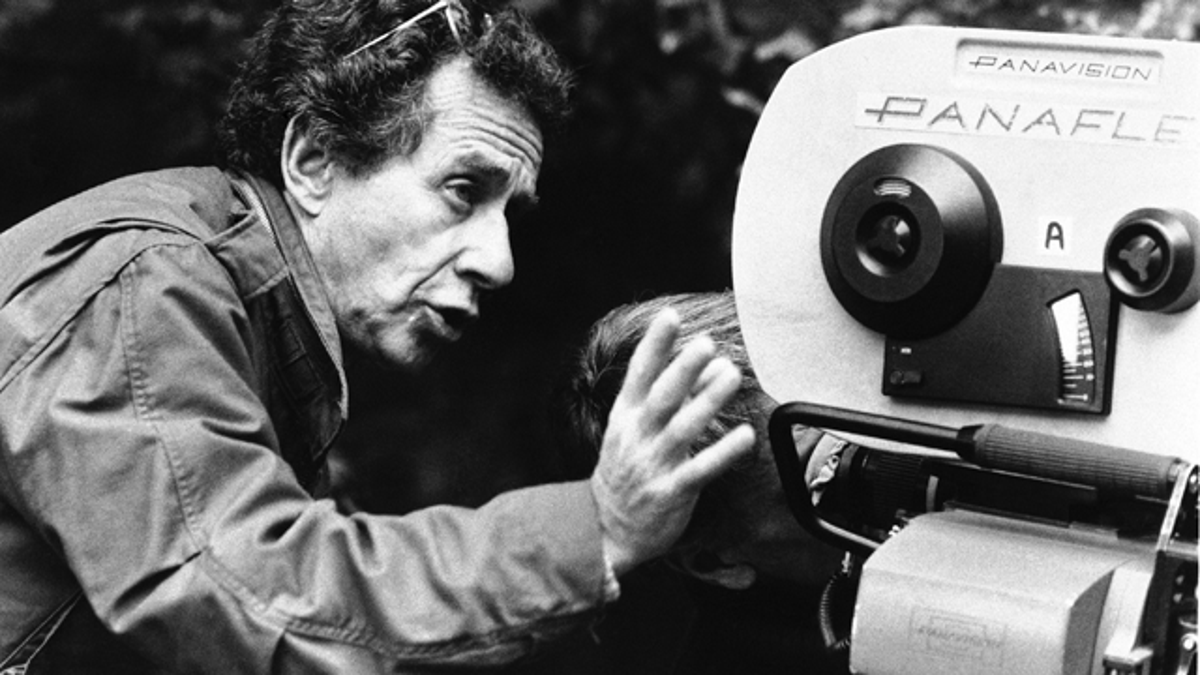

Director Arthur Penn, a myth-maker and myth-breaker who in such classics as "Bonnie and Clyde" and "Little Big Man," refashioned movie and American history and sealed a generation's affinity for outsiders, died Tuesday night, a day after his 88th birthday.

Daughter Molly Penn said her father died at his home, in Manhattan, of congestive heart failure. Longtime friend and business manager Evan Bell said Wednesday that Penn had been ill for about a year. A memorial service would be held before the end of the year. Penn's older brother was photographer Irving Penn, who died in October 2009.

After first making his name on Broadway as director of the Tony Award-winning plays "The Miracle Worker" and "All the Way Home," Penn rose as a film director in the 1960s, his work inspired by the decade's political and social upheaval, and Americans' interest in their past and present.

"Bonnie and Clyde," with its mix of humor and mayhem, encouraged moviegoers to sympathize with the lawbreaking couple from the 1930s, while "Little Big Man" told the tale of the conquest of the West with the Indians as the good guys.

"A society would be wise to pay attention to the people who do not belong if it wants to find out ... where it's failing," Penn once said.

Penn's other films included his adaptation of "The Miracle Worker," featuring an Oscar-winning performance by Anne Bancroft; "The Missouri Breaks," an outlaw tale starring Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson; "Night Moves," a Los Angeles thriller featuring Gene Hackman; and "Alice's Restaurant," based on the wry Arlo Guthrie song about being turned down for the draft because he had once been fined for littering.

Penn was most identified with "Bonnie and Clyde," although it wasn't a project he initiated or, at first, wanted. Beatty, who earlier starred in Penn's "Mickey One" and produced "Bonnie and Clyde," had to persuade him to take on the film, written by Robert Benton and David Newman and inspired by the movies of the French New Wave. (Francois Truffaut and Jean Luc-Godard each turned down offers to direct the film).

Penn was in his 40s when he made "Bonnie and Clyde," but his heart was very much with the gorgeous stars, played by Beatty and Faye Dunaway, and with the story, as liberal in its politics as it was with the facts -- a celebration of individual freedom and an expose of the banks that had ruined farmers' lives.

Released in 1967, when opposition to the Vietnam War was ballooning and movie censorship crumbling, "Bonnie and Clyde" was shaped by the frenzy of silent comedy, the jarring rhythms of the French New Wave and the surge of youth and rebellion. The robbers' horrifying death, a shooting gallery that took four days to film and ran for less than a minute, only intensified their appeal.

"I thought that if were going to show this (violence), we should SHOW it," Penn said in the documentary "A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies."

"We should show what it looks like when somebody gets shot." TV coverage of Vietnam, he added, "was every bit, perhaps even more, bloody than what we were showing on film."

With the glibbest of promotional tag lines, "They're young ... they're in love ... and they kill people," it was a film that challenged and changed minds. Beatty worked for a reduced fee because the studio, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, was convinced that "Bonnie and Clyde" would flop. Released in August 1967, then rereleased early in 1968 in response to undying attention, "Bonnie and Clyde" appalled the old and fascinated the young, widening a generational divide not only between audiences, but critics.

The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards, with Estelle Parsons winning for best supporting actress, and is regarded by many as the dawn of a golden age in Hollywood, when the old studio system crumbled and performers and directors such as Penn, Beatty, Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese enjoyed creative control.

Penn, who had fought -- and lost to -- the studios over the editing of such early films as "The Left Handed Gun" and "The Chase," now was able to realize a long-desired project -- an adaptation of "Little Big Man," based on the Thomas Berger novel.

"Originality is filtered out like tar is filtered out of cigarettes," Penn once complained. "I have not had a lot of success with the suits -- or the dresses. Executives are executives. They're going to interfere as much as they can.

"('Little Big Man') didn't happen until I had so much clout I sort of made it happen."

None of Penn's other films would have the impact of "Bonnie and Clyde," but the director regarded "Little Big Man," released in 1970, as his greatest success, with Dustin Hoffman playing the 121-year-old lone survivor of Custer's last stand. It was, again, a violent and romantic overturning of the past and an angry finger pointed at the war and racism of the present.

Penn earned Academy Award nominations for both films and for his first movie, "The Miracle Worker," based on the Broadway show about Helen Keller and her teacher, Anne Sullivan, played by Bancroft. Among Penn's other stage credits: "All the Way Home," which won both the Tony and Pulitzer Prize in 1961 as best play; "Two for the Seesaw"; the musical version of "Golden Boy"; and "Wait Until Dark."