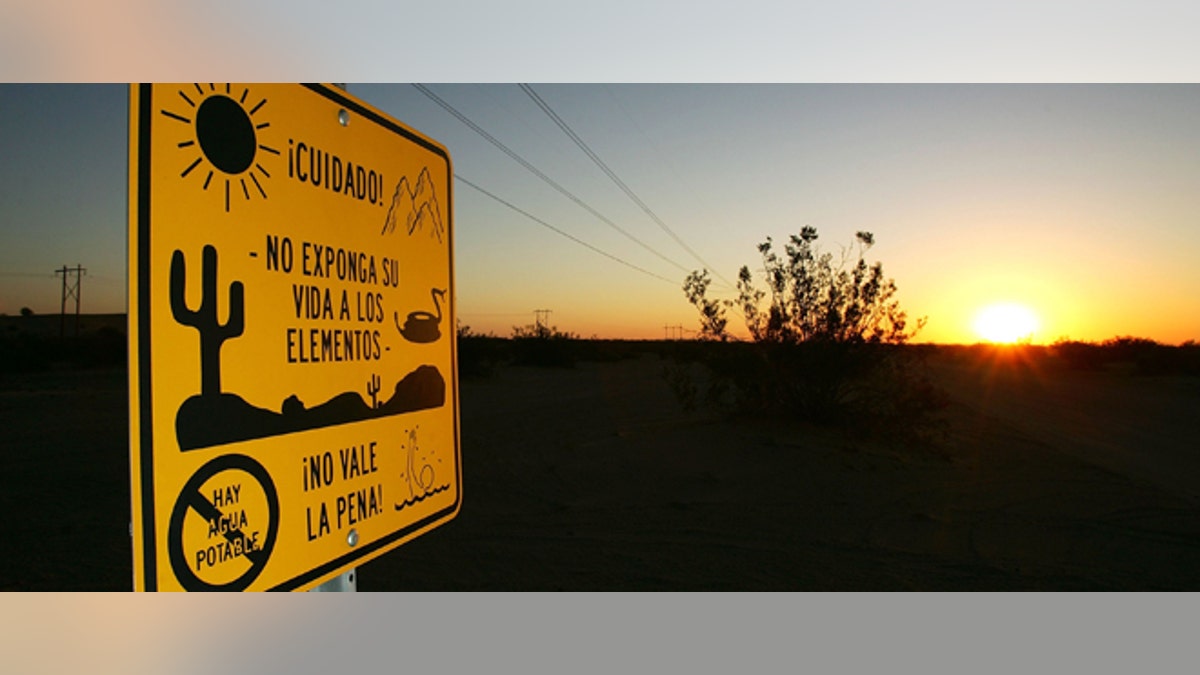

WINTERHAVEN, CA - OCTOBER 08: An official south-facing sign cautions north-bound illegal immigrants of dangers in the desert trek adding that it is not worth the risk, along the US-Mexico border where no fence divides the two nations near the Imperial Dunes on October 8, 2006 west of Winterhaven, California. The warning includes heat, rugged terrain, rattlesnakes, lack of drinking water, and the risk of drowning in the All American Canal which parallels the border a short distance to the north.. US Fish and Wildlife Service wardens and environmentalists warn that a proposed plan by US lawmakers to construct 700 miles of double fencing along the 2,000-mile US-Mexico border, in an attempt to wall-out illegal immigrants, would also harm rare wildlife. Wildlife experts say cactus-pollinating insects would fly around fence lights, birds that migrate by starlight in the desert wilderness would be confused; and large mammals such as jaguars, Mexican wolves, Sonoran pronghorn antelope, and desert bighorn sheep would be blocked from migrating across the international border, from California to Texas. (Photo by David McNew/Getty Images) (2006 Getty Images)

Despite initiatives set in place by the U.S. Border Patrol that have resulted in a dip in deaths suffered by illegal border-crossers, dangerously high summer temperatures and the harsh environment still make some areas especially hazardous.

The U.S. Border Patrol has seen a 12 percent decrease in the number of deaths between 2009 and 2011 along the U.S.-Mexico Border from a seven-year high of 420 to 368.

"Crossing the border has become increasingly dangerous as smugglers have moved migrants to more remote areas with treacherous terrain and extreme weather conditions where temperatures can reach 115 degrees," said Kerry Rogers, spokeswoman, U.S. Border Patrol.

Rogers added that the decrease could be attributed to an increase in manpower along the border, improved roads and fencing, and in technology like cameras and sensors.

However not all border sectors are created equal.

The number of deaths in the Tucson sector -- which includes the desolate deserts of Arizona's Pima County, as well as the Laredo and Rio Grande sectors in Texas -- remains disproportionately higher than the rest of the country.

The Tucson sector’s migrant death rate of 191 in 2011 is nearly three times that of the Rio Grande Valley sector, which has the second highest with 66. This was a dramatic spike from 29 deaths the previous year and has continued to rise to 69 in 2012, with three months remaining the federal fiscal year.

We have rugged environments that people are traveling on foot through...Of those we can identify, the majority die from heat related illnesses.

After the Laredo sector, there is a precipitous drop in deaths with the Del Rio sector, also in Texas, with 18.

Gregory Hess, Pima County Chief Medical Examiner, said his office saw a spike in migrant deaths in 2010 with 230, but they dropped to 184 in 2011. Deaths peak between June through August, but do continue steady throughout the year.

“We have rugged environments that people are traveling on foot through,” Hess said. “Of those we can identify, the majority die from heat-related illnesses.”

While decomposition makes it difficult to tell the cause of death of many of the border crossers, the Pima County Forensic Science Center Annual Report for 2011 stated that 28 percent of the victims succumbed to the harsh desert elements, with over 75 percent of them being males.

Larger groups of border crossers with little or no supplies for survival in the desert are adding to the death toll.

“We are seeing larger groups of 60-70 people being brought over,” said Corinne Stern, Chief Medical Examiner for Webb County, Texas. “I know of one group of 10 who were brought across the border with only two gallons of water, it’s very sad.”

According to Border Patrol statistics, Stern’s sector has averaged some 48 deaths per year since 2007.

Both Stern and Hess said they not only try to determine the cause of death, but also return the remains to the family through a close relationship with the Mexican consulate and those of other Latin American countries migrants originate from.

“It is a necessary responsibility we assume as doctors and law enforcement who choose to live and work on the border,” Stern said.

Both Stern and Hess said the examination and disposition of migrant remains comprises around 15 percent of their budget. Stern said the expense is not a burden to her budget, which is determined by the caseload of the previous year.

“These deaths are indigenous to our location so we consider it when doing our budget,” she said.

As the front line of defense on the border, the Border Patrol is often the first line of protection for migrants in medical trouble.

“The Border Patrol takes multiple steps to improve safety and prevent deaths of illegal migrants," Rogers said, adding that the Border Safety Initiative (BSI) of 1998 was designed to reduce migrant deaths and make the border safer for agents, border residents, and migrants, by training agents as first responders, EMTs and paramedics.

Electronic rescue beacons have been placed across the border, which, when activated by a migrant in distress, allows agents to pinpoint their exact location and respond quickly with trained emergency personnel. The Border Patrol also formally tracks and documents deaths and rescues and uses this data to identify trends, which in turn allows them to deploy additional resources in high-risk areas.

One group that has been critical of the Border Patrol is No More Deaths, a volunteer organization that provides water and safety supplies to migrants in high traffic areas in Arizona deserts.

While repeated attempts to contact the group were not returned, a 2011 report titled “A Culture of Cruelty: Abuse and Impunity in Short-Term U.S. Border Patrol Custody” chastises Border Patrol tactics.

“The abuses individuals report have remained alarmingly consistent for years, from interviewer to interviewer and across interview sites: individuals suffering severe dehydration are deprived water; people with life-threatening medical conditions are denied treatment; children and adults are beaten during apprehensions and in custody,” the report stated. “Family members are separated, their belongings confiscated and not returned; many are crammed into cells and subjected to extreme temperatures, deprived of sleep, and threatened with death by Border Patrol.”

Stern argued that No More Deaths allegations are too harsh and he has never witnessed such treatment of migrants.

“I have never seen them to be anything but compassionate and respectful,” Stern said. “We don’t think about any of this as a burden, this is our community.”