Viral vanish: What happened to Joseph Kony?

Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army rose to fame in 2012 for abducting more than 38,00 adults and another 38,000 children, forcing thousands of boys into becoming ‘child soldiers’ and girls held as spoils of war, deemed ‘wives’ or sex slaves. Despite all the global attention, public pressure and anger, Kony is still a free man operating from within the jungles of Africa.

Eight years ago, Joseph Kony soared from the fringes of the foreign policy establishment and became a household name across the United States – due in large part to a viral video titled “Kony 2012” by the Washington-based non-government organization Invisible Children.

Commander Kony and the shocking abuses committed by his self-styled Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a Ugandan rebel group, were brought to a wincing light in the 30-minute video, which included powerful testimonies from young, broken boys begging to die, amplified over a hauntingly soft soundtrack.

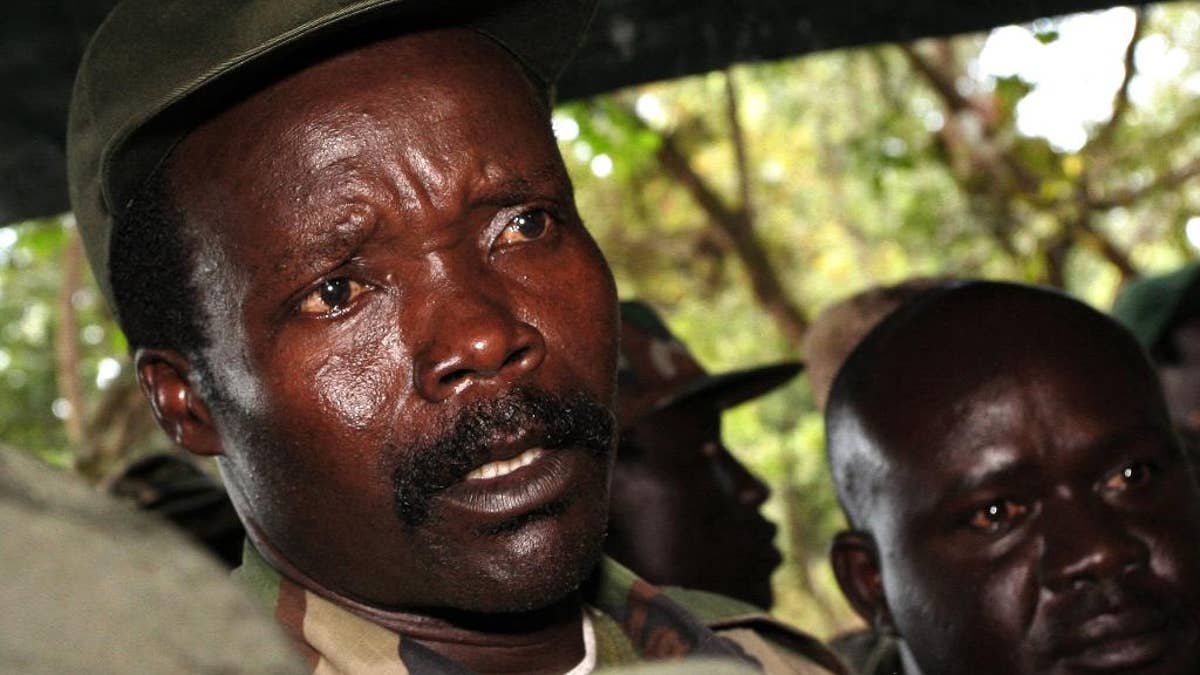

Joseph Kony, the leader of the Lord's Resistance Army, answers journalists' questions following a meeting with UN humanitarian chief Jan Egeland at Ri-Kwangba in Southern Sudan on Nov. 12, 2006. Kony has been Africa's most notorious warlord for three decades. Now that the United States and others are ending the international manhunt for him and his Lord's Resistance Army, it appears Kony may never be brought to justice. (AP Photo/Stuart Price, File) (The Associated Press)

But despite all the global attention, public pressure and anger ignited overnight toward Kony, subsequently mobilizing some of the world’s most potent militaries to bring him to justice, he is still a free – albeit less powerful – man operating from within the jungles of Africa.

Kony is now estimated to be around 58 years old. He was born to a Catholic father and Anglican mother and spent part of his childhood as an altar boy before dropping out of school around age 15.

“Where the LRA once boasted more than 2,000 fighters, efforts of the African security forces, with U.S. advice and assistance, reduced the group’s active membership and eroded its capacity,” a U.S. State Department official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Fox News. “However, residual elements remain, particularly along the Central African Republic (CAR) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) border. The LRA reportedly continued to recruit and use child soldiers.”

WHO IS THE FBI’S MOST WANTED AMERICAN TERRORIST? MEET JEHAD SERWAN MOSTAFA

Even before the advent of the viral video, Kony’s LRA was on the hotlist of the U.S. government, which designated it a foreign terrorist organization soon after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. In 2008, then-President George W. Bush directed the U.S. Africa Command to support and equip Ugandan government troops to home in on Kony’s encampments, but he ultimately evaded capture.

In 2011, President Barack Obama reinvigorated the effort by bolstering the number of U.S. troops deployed to assist local forces in eliminating Kony and his upper echelon comrades from the war theater. In 2013, a $5 million bounty was placed on his head by the U.S. State Department – but to no avail.

Then in April 2017, the joint operation between the U.S. and Uganda to track down Kony was shuttered under the cloak that the LRA no longer posed a threat to Africa’s security.

Josh Lipowsky, a senior researcher for the Counter Extremism Project (CEP), concurred that while the LRA has “weakened, it has not disappeared.”

“Uganda initiated an amnesty program back in 2000 that saw some 13,000 LRA fighters lay down their weapons and return home. By 2012, the LRA had fewer than 100 men who had splintered into factions spread across Africa,” he explained. “It simply doesn’t have the infrastructure that it once did. That is not to say that the group cannot still be dangerous.”

Troops from the Central African Republic stand guard in April 2012 at a building used for joint meetings between them and U.S. Army special forces, in Obo, Central African Republic, where U.S. special forces have paired up with local troops and Ugandan soldiers to seek out Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army (LRA). AA rebel in charge of communications for warlord Joseph Kony has surrendered to Ugandan forces, the military said on March 30, 2017, shortly after the U.S. indicated it was pulling out of the international manhunt for one of Africa's most notorious fugitives. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File) (The Associated Press)

Kony’s LRA movement was sparked in the mid-1980s under the guise of defending those in Northern Uganda from the new regime of Yoweri Museveni.

However, by the 1990s, Kony’s operation had descended into an insurgency that waged war against the civilian population, the very people Kony initially proclaimed to be protecting. Some 38,000 adults were abducted and a further 38,000 children – with thousands of boys routinely forced into becoming “child soldiers” and girls held as spoils of war, deemed “wives” or, more jarringly, sex slaves.

Victoria Nyanjura was one of those girls whose childhood and innocence was ripped from her in a horrific miscarriage of justice. She was a 14-year-old student at a Catholic boarding school when scores of LRA soldiers broke through the school’s barricades and stole Nyanjura and almost 140 others from their beds.

She remembers everything about that night. The way the calm and stillness of Oct. 9, 1996, was shattered by raucous screaming and soldiers threatening them with grenades. She was dragged off into the darkness and tied up so that she could not run.

“Late at night, they are owning you. You have no consent. When you are abducted, you have no voice. If you want to live at the end of the day, you must comply,” recalled Nyanjura, who was held in captivity for eight years. “There were times when I felt as if I would be better off if I died.”

But soon cradling two newborn babies of her own, Nyanjura knew she needed to keep fighting for their lives – and it was her faith that propelled her through.

“I had to look deeper, I had to continue praying as the war intensified. I had to find food for my hungry children,” she said. “I believed that one day God would lead me home.”

Nyanjura finally found a chance to escape on foot, running through the thickets and shielding her tiny children from the heavy rains with her scarf for days that stretched on and on. When she made it to the safety of a camp, she was then forced to confront the stigma and the gaping internal wounds of her time under Kony's command that may never fully heal.

“For so long I did not want to expose my children to what happened. It was only last year that I started to tell them,” said Nyanjura. She is now 38 and, in addition to supporting other survivors, completing a master's degree in global affairs with a concentration in international peace studies at Notre Dame. “When I tell my story, I still feel like I am being abducted in the night. I try running in the dream, but they are holding me. What I have gone through I can never get out of my mind.”

A survivor of LRA captivity, Victoria Nyanjura escaped the abusive LRA regime (Courtesy Victoria Nyanjura)

The LRA's reign of terror led hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes as bullets and mortar fire rained down on what little they possessed. Body parts and facial features were hacked off, and bones were left to pile up and rot under the scorching sun.

For decades, much of the fractured area was something of a place in suspension.

“The LRA really sought to distinguish themselves by cutting off people’s noses, their lips, their limbs. I met with a number of their young boys and girls who were able to escape, and they talked about how the LRA abducted these kids and would tie a rope around their neck and run out into the jungle with them,” recalled Jan Egeland, who then served as the United Nations' undersecretary-general for humanitarian affairs and emergency relief coordinator. “The leaders would break them down mentally, brainwash them, give them a gun, and then take them back to their village (to kill). These brainwashed child soldiers were fearless and had nothing to lose.”

Not only did Egeland meet with Kony’s young victims, but he was the first Westerner to meet with the shadowy warlord himself deep in the morass at the juncture between Sudan and the Congo in 2006.

“He was surprisingly underwhelming, very softly spoken. I tried to get him to look me in the eyes, but he looked down the whole time,” Egeland remembered.

U.S. Army special forces Captain Gregory, 29, from Texas, right, who would only give his first name in accordance with special forces security guidelines, speaks in 2012 with troops from the Central African Republic and Uganda who are searching for Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), in Obo, Central African Republic. The Obama administration said in January 2015 that it has taken into custody a man claiming to be Dominic Ongwen, a top member of Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army who is wanted by the International Criminal Court, after the man surrendered to U.S. forces in the Central African Republic. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File) (The Associated Press)

He attributes their ability to elude detection largely to Kony and the LRA being “more paranoid and careful than other militia groups.” They never used phones and did not use a single vehicle for operations – preferring to cover vast areas on foot and move in small groups.

Kony’s rampage spread into much of the volatile region, with attacks taking place across South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic. The militia thrived under the veil of protection at bases inside Sudan, where they received support from dictator Omar al-Bashir as the Ugandan forces launched cross-border attacks in their quest to defeat the guerrilla group.

PRO ATHLETES UNITE TO BRING WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL AND HEALING TO THOSE TRAPPED IN WAR

In 2005, Kony was indicted by the International Criminal Court in The Hague on 21 charges of war crimes and a further 12 for crimes against humanity. The case against him is open, as is the Interpol red notice, which was launched the following year.

While some scholars point to Kony’s outfit as being rooted in tenets of Christian extremism, over the years the “General” has drawn on mystical and spiritual ideologies – declaring himself to have reverent powers and to be something of a “prophet.”

Kony, as underscored by several sources, is now purported to be running his militia, which official estimates say is comprised of few more than a hundred fighters, from Sudan-controlled territory in Kafia Kingi.

According to one Western intelligence source that covers the region, Kony is believed to have been struck down with severe health concerns around a year ago – likely suffering from sexually transmitted infections. He allegedly sought treatment in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.

Sasha Lezhnev, deputy director of policy at the George Clooney-backed The Sentry – which works to end mass atrocities in Africa’s deadliest conflict zones – told Fox News that the significant diminishing of LRA numbers had been a result of numerous special forces operations and defection campaigns in Uganda.

“But Joseph Kony, his sons, and the LRA remain a threat to civilians, mainly in the eastern Central African Republic,” Lezhnev stressed. “The LRA also continues to poach elephants and trade ivory, as well as trade gold and diamonds for ammunition and supplies. That said, it's now not as powerful as some other groups.”

A representative for Invisible Children, the nonprofit behind the 2012 short film, emphasized that although Kony no longer hits the headlines, the LRA poses a daily threat to locals, and funding to help victims has largely dried up.

In 2019, the LRA abducted more than 220 civilians and, according to Invisible Children’s conflict tracker, at least half were children – with at least 49 who are still missing.

Kenyan officials display some of more than 1,600 pieces of illegal ivory found hidden inside bags of sesame seeds in freight traveling from Uganda, in Kenya's major port city of Mombasa, Kenya, on Oct. 8, 2013. Warlord Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army rebel group is increasingly trafficking in ivory and minerals to obtain weapons and other supplies to be used in the jungles of central Africa, watchdog groups said in a report released in 2014. (AP Photo, File) (The Associated Press)

Several other U.S.-based sources told Fox News that private contracting groups have routinely pinpointed Kony’s exact whereabouts in recent years in the hopes of retrieving the multimillion-dollar reward, but have generally been told to “back off” by higher Western powers-that-be. Some have indicated it may be because the more Christian-orientated group keeps Islamic insurgencies in check, while other critics have contended that Kony’s area of operation is not known for jihadist terrorists.

According to Foreign Policy magazine, more than $800 million in U.S. taxpayer money was spent by the Pentagon to track down the elusive militia leader prior to 2017. Despite his ongoing elusiveness, a U.S. State Department official told Fox News that the government continues to be concerned about the impact of Kony and the LRA on civilian populations in Central Africa.

“The United States continues to support justice and accountability for all those credibly accused of war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity,” the official noted. “We continue to assist the CAR and the DRC governments and their people to end what remains of the threat posed by the LRA and mitigate the consequences of LRA atrocities.”

The State Department also utilizes U.S. Agency for International Development programming in the region for communities in recovery, funding efforts centered on trauma healing and community-based reintegration activities and crisis monitoring.

So what impact would it now make if Kony was killed or captured?

“At this point, it wouldn’t make much of a practical difference as the LRA has not claimed any major operations since 2010 and is no longer under a centralized command. It would, however, come across as a moral victory against one of the great villains of the region,” added Lipowsky of the Counter Extremism Project. “Kony’s death or capture now would allow the U.S. to declare mission accomplished resolutely.”