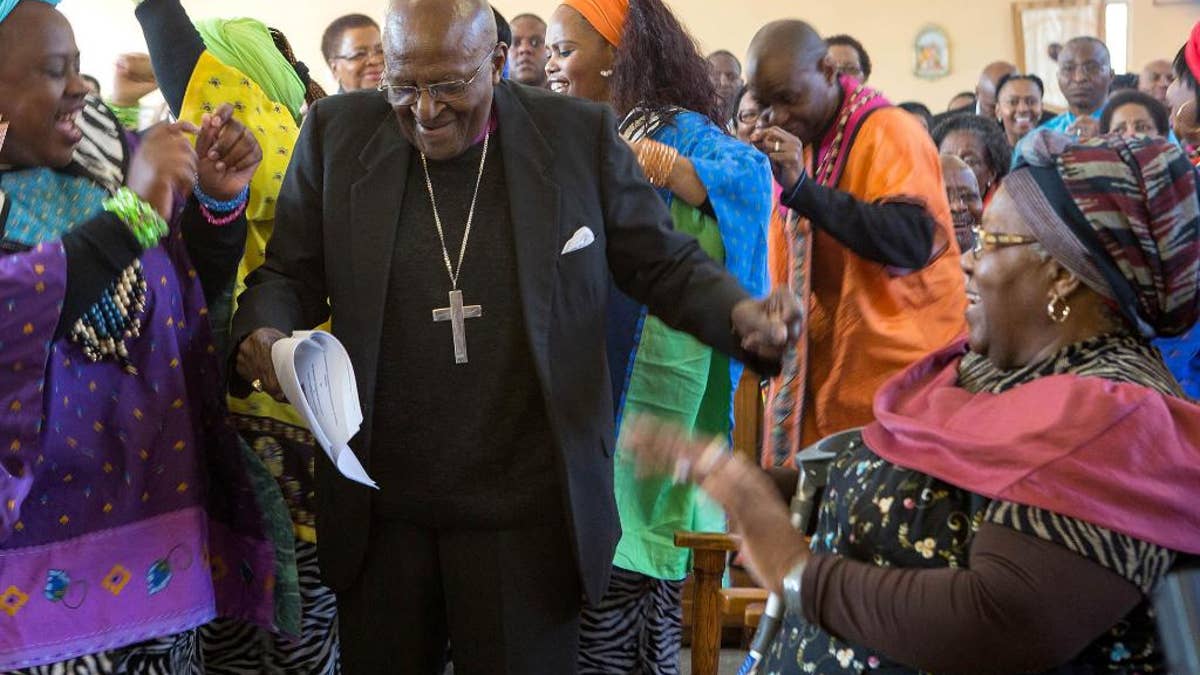

In this photo taken Saturday, July 4, 2015, retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, centre, breaks into dance after renewing his wedding vows to his wife of 60 years, Leah, right, during a service in the Holy Cross Anglican Church in Soweto, Johannesburg. (AP Photo) (The Associated Press)

JOHANNESBURG – Retired archbishop Desmond Tutu, affectionately known to many South Africans as "Arch," kissed his bride of 60 years, Leah.

The lovebirds, as one clergyman described them, renewed their 1955 wedding vows this weekend in a buoyant ceremony in which 83-year-old Tutu, slower of step and speech than during his years as an impassioned opponent of apartheid, sashayed stiffly near the altar. Arms outstretched, he bent low as choristers belted out song in the Holy Cross Anglican Church in the Soweto area of Johannesburg.

The three-hour celebration on Saturday was a kind of homecoming for Tutu, who used to live near the church in a district that became a crucible for resistance to the white minority rule that ended in 1994. It was also a contemplation of love, marriage and family that ended with the Tutus' four children and other relatives surrounding the elderly couple.

"You can see that we followed the biblical injunction: We multiplied and we're fruitful," Tutu told the congregation. "But all of us here want to say thank you ... We knew that without you, we are nothing."

The humor and humility were Tutu trademarks. For decades, he has charmed, cajoled and beseeched on matters of unity, forgiveness and good and evil, comparable to the moral stature of the late Nelson Mandela, a prisoner during white rule, a fellow Nobel Peace Prize laureate and South Africa's first black president. Tutu still speaks up even though he announced his retirement from public life in 2011.

"He's one of the people now who represent the conscience of the nation," Thabo Mbeki, a former South African president who attended the Tutu ceremony, told The Associated Press. "It comes from the track record he's established in terms of bringing about the change that the country needed."

Mandela's widow, Graca Machel, sat beside Mbeki, who chuckled as she gently chided an AP reporter asking for comment while congregants received Holy Communion.

"I don't think we should be giving interviews in church. The service is going on," she said.

Tutu was awarded the Nobel prize in 1984 for campaigning against apartheid, chaired the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission that investigated past atrocities and became a critic of South Africa's current government. He befriended the Dalai Lama, dived into global challenges such as poverty and climate change and joined efforts to solve conflicts in Sudan and elsewhere. His blunt remarks sometimes angered partisans who accused him of being biased or out of touch.

The church event resembled a stage musical starring the Tutu clan with backup from the Soweto Gospel Choir. Gowned clergy swayed to the rhythm. Singers twirled in the pews.

Desmond Tutu was dressed in black and had a crucifix around his neck. Clad in a traditional headdress, Leah Tutu walked with a crutch. The couple also renewed their vows on July 2, their wedding anniversary, in St. George's Cathedral in Cape Town, where they live.

Tutu, a former teacher, got to know his wife-to-be through her friendship with his sister Gloria, and Leah also attended a school where Tutu's father was the headmaster.

"Leah is the glue that holds it all together," says the website of a foundation carrying the couple's names. Like any family, the Tutus have struggled. Desmond Tutu has been treated for prostate cancer for many years. In May, South African police said they were investigating a case of property damage in what appeared to be a family dispute involving a Tutu granddaughter.

In a sermon, daughter Naomi Tutu compared her parents' love to that of Romeo and Juliet, or Mark Antony and Cleopatra — except with a "better ending."

"My parents refused to be separated," she said. "Their primary loyalty was to one another. We, who came after, were gifts given to them."