Nov. 7, 2016: The Marza family were among 226 Assyrian Christians taken captive by the Islamic State group in a February 2015 attack on their villages in Syrias Khabur River valley. It took a year to free the hostages, and only after three were killed and millions of dollars gathered by the Assyrian diaspora worldwide was paid to the militants, and in the end the Khabur region has been totally emptied of the tiny, centuries-old minority community. (AP Photo/Michael Probst)

SAARLOUIS, Germany – Deep inside Syria, a bishop worked secretly to save the lives of 226 members of his flock from the Islamic State group — by amassing millions of dollars from his community around the world to buy their freedom.

The Assyrian Christians were seized from the Khabur River valley in northern Syria, among the last holdouts of a minority that had been chased across the Mideast for generations. On Feb. 23, 2015, IS fighters attacked 35 Christian towns simultaneously, sweeping up scores of people.

It took more than a year, and videotaped killings of three captives, before all the rest were freed.

Paying ransoms is illegal in the United States and most of the West, and the idea of giving money to the Islamic State group is morally fraught, even for those who saw no alternative.

"You look at it from the moral side and I get it. If we give them money we're just feeding into it, and they're going to kill using that money," said Aneki Nissan, who helped raise funds in Canada. But "to us, we're such a small minority that we have to help each other."

The Marza family were among those taken captive from their village. It took a year to free the hostages, and only after three were killed and millions of dollars gathered by the Assyrian diaspora worldwide was paid to the militants. (AP Photo/Michael Probst)

The Khabur families trace their heritage to the earliest days of Christianity. To this day, they speak a dialect of Aramaic, believed to be the native language of Jesus.

When the villages were attacked, fleeing residents phoned cousins, sons, daughters, friends — Assyrians who had left the region in waves for the West. In the chaos, no one was sure how many were taken captive — but everyone was certain they were going to die.

As days stretched into a week, it became clear IS had other plans.

The group told the 17 men captured from one village, Tal Goran, they could have their freedom but with a catch. Four female captives would remain, and one of the men had to deliver a message to their bishop in the town of Hassakeh about 40 miles away, and return with an answer. The extremists demanded $50,000 per person for the whole group.

Abdo Marza reluctantly agreed. His 6-year-old daughter was one of the captives.

It took the bishop, Mar Afram Athneil, three days to make a decision, as he consulted with members of the church around the world on what to do. Then he gave Marza a sealed envelope, with no explanation.

When Marza handed it over, the IS extremist broke into a smile. "Your bishop is a very smart man." With that, his daughter and three old women were freed.

Athneil began secret negotiations for the remaining captives.

In California, Assyrian filmmaker Sargon Saadi packed his gear, hoping to learn what had happened to the Khabur villages. He found them almost deserted.

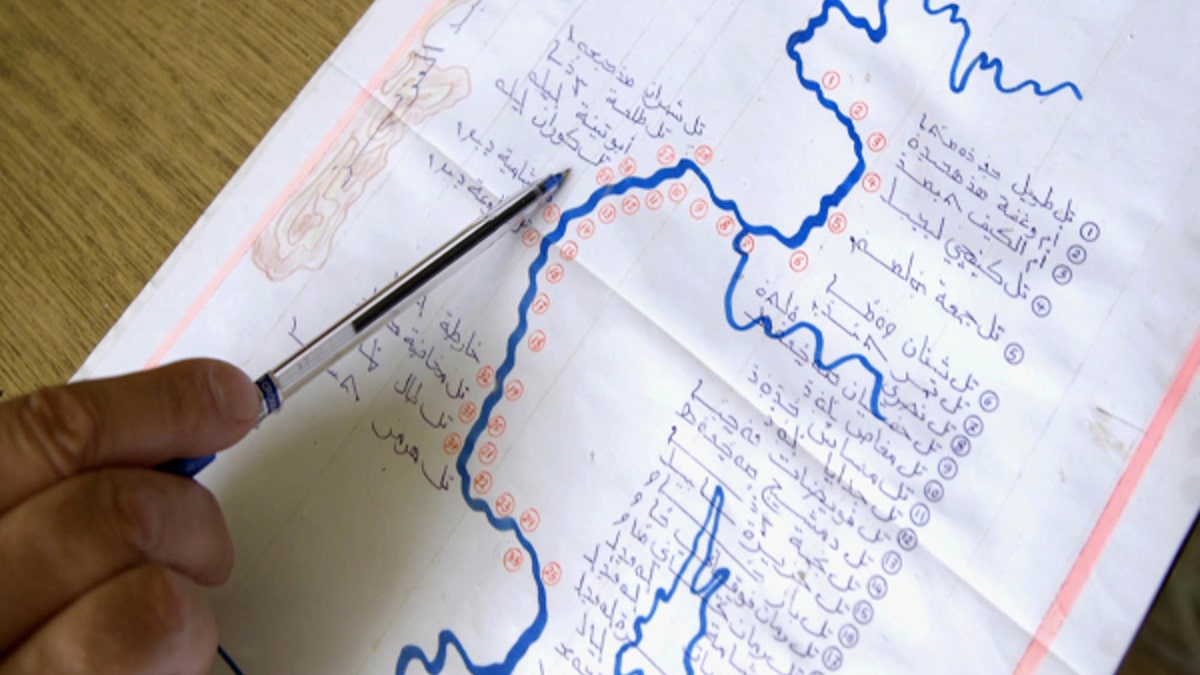

A map shows the string of Assyrian Christian villages attacked by the Islamic State group along northern Syrias Khabur River in this frame grab from Silence After the Storm, a documentary about the villages by Assyrian filmmaker Sargon Saadi. The villages now stand virtually deserted after the militants attacked in February 2015, taking more than 200 men, women and children captive and driving out the rest, all members of a community that traces its heritage back to the beginnings of Christianity. (Sargon Saadi via AP)

"We didn't know why they took them, we didn't know where they took them, what they wanted to do with them," Saadi said.

When word filtered down about the ransom, the price was daunting. IS's starting demand of $50,000 a person would mean more than $11 million for the remaining captives.

"There's no easy way to give them money. It's very dangerous, it's also illegal in many countries," Saadi said.

The calls for donations went out across social media. In Germany, Assyrian entrepreneur Charli Kanoun persuaded the government to accept the Tal Goran hostages, and then he began fundraising for the others. Outside London, Andy Darmoo also fundraised while running his chandelier business.

On May 26, two women were freed. On June 16, one man was released. On Aug. 11, 22 more people were liberated. Many in the diaspora hoped the ordeal was nearly over.

Then in September 2015 came the video showing three Khabur men, dressed in orange, being shot to death.

"When that happened, everybody went crazy and money started flying in from all over," Saadi said. "Assyrians don't have an army to go rescue them. They don't have SWAT teams, they don't have SEAL 6. The only option they have is to pay ransom."

The Islamic State group has made a fortune off the desperation of hostages. A United Nations resolution from December 2015 called on governments "to prevent kidnapping and hostage-taking committed by terrorist groups and to secure the safe release of hostages without ransom payments or political concessions."

But while no government appeared to stop the fundraising, the Assyrians say no country stepped in to free the captives either.

Brokered by the bishop, Athneil, negotiations resumed in mid-fall. The money went into an account in Irbil, Iraq.

From November, releases took place every few weeks.

On Feb. 22, 2016, a final list of 43 names was sent to the bishop. The last Khabur captives were on their way out.

But when the bus arrived in Hassakeh, only 42 hostages were on board. Sixteen-year-old Maryam David Talya had been pulled off at the last checkpoint by an IS guard, Kanoun said.

After another agonizing month of negotiations, Maryam stumbled into the arms of her parents.

How much was ultimately paid remains a mystery. The bishop, the only person with a full accounting, declined to speak to The Associated Press.

Those involved credit him for saving the lives not just of the hostages but of hundreds of other Assyrians who fled the war zone. The Khabur valley is now all but empty of its Christians.

"Honestly, this man should go down as a saint, the things that he's done, the sacrifices he's made to help these people," Nissan said. "He's refusing to leave Syria until all his flock is secured."