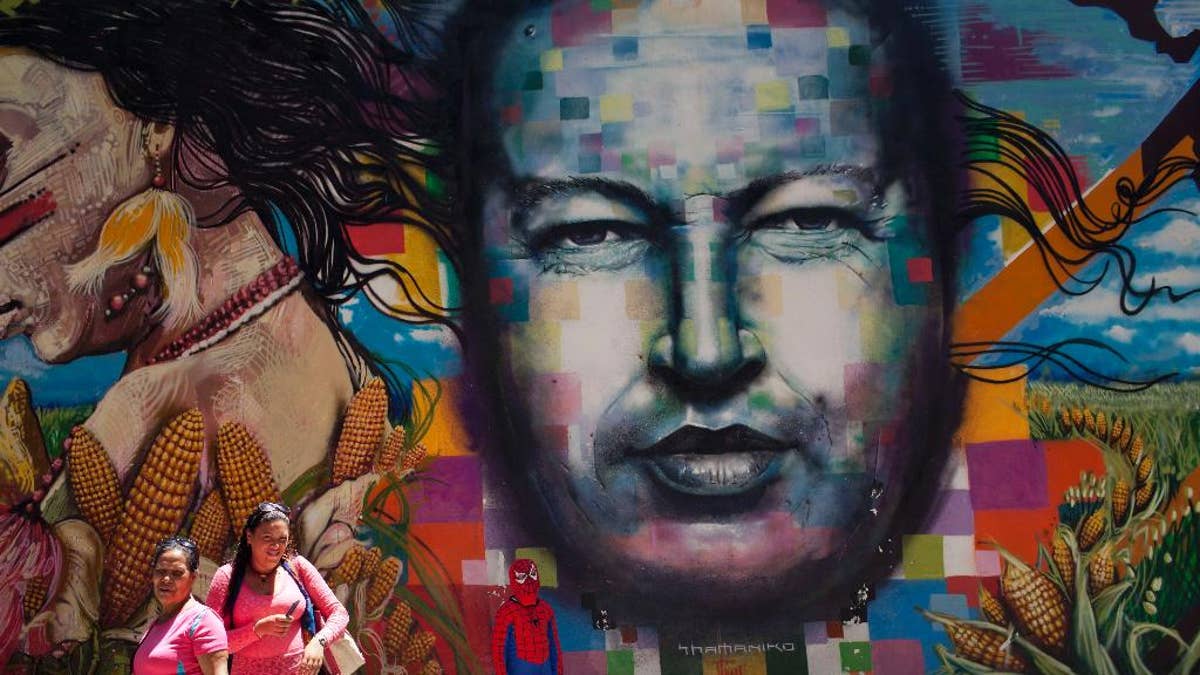

A boy dressed in a Spiderman costume poses for a photo next to a mural of Venezuela's late President Hugo Chavez painted on a wall of the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas, Venezuela, Tuesday, March 4, 2014. He’s been dead a year, but Chavez’s face and voice are everywhere. He bangs out the national anthem on state radio every morning and the national guard has even blasted his voice reciting poetry to drive rock-throwing protesters off the street. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) (The Associated Press)

CARACAS, Venezuela – Hugo Chavez always said his socialist project would last decades, but a year after the Venezuelan president's death even some of his most fervent supporters are having their doubts.

The desperation of Venezuelans is growing along with the length of the queues outside state-run markets that reflect the economy's downward spiral and helped trigger a wave of protests in mid-February which have claimed at least 18 lives.

Recent elections indicate that a majority of Venezuelans remain loyal to Chavez's legacy, but many are less sure of those he chose to follow him.

"When the head of household is absent, as we say around here, things start to get out of control," said Pablo Nieves, a community leader in the poor 23 de Enero district of Caracas. "If he were still with us, it would have never gotten to this."

President Nicolas Maduro, the hand-picked successor of Chavez, organized 10 days of commemorative activities to mark Wednesday's anniversary of the larger-than-life leader's death from cancer at age 58.

A civilian-military parade is to be followed by speeches by allied presidents expected to include Evo Morales of Bolivia and Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua as well as the debut on state TV of director Oliver Stone's documentary "My Friend Hugo."

The celebrations honor a charismatic, folksy, combative leader who transformed Venezuela during a 14-year reign by championing its downtrodden. He lifted a good share of the country's population out of poverty by sharing the nation's oil export bounty with people who had nearly always been excluded.

The government has encouraged devotion to the late president that is sometimes openly religious. One small chapel in the 23rd de Enero district is dedicated to St. Hugo Chavez.

"There's no way I could pay for the 14 years I lived with Hugo Chavez," said Beatriz Ramirez, a 55-year-old teacher and lawyer who deposited flowers in the chapel. "All I learned of geography, history, mathematics, economy, politics, culture I learned from my comandante."

The opposition did not call any protests for Wednesday in the capital, though Foro Penal, which provides lawyers for detainees, did announce a march in the central industrial city of Valencia.

The opposition is struggling to broaden its support and to overcome an image among many that it is elitist — a perception eagerly fed by government backers.

The government has denounced protests as an attempted coup and it has been aided in repressing demonstrations by menacing "collectives" of motorcycle-riding thugs. The protesters blame the collectives for some of the 18 deaths the government says the unrest has reaped.

More than 1,000 protesters have been detained and 72 people face charges, including eight members of the SEBIN political police.

Maduro's government, meanwhile, has shown itself unable to halt 56 percent annual inflation and crippling currency controls that have fueled a growing scarcity of consumer basics — from milk to flour to cooking oil. The central bank's scarcity index was its highest-ever in January at 28 percent.

While this nation has the world's largest proven oil reserves, former oil executives are driving cabs and workers from other collapsed industries struggle to find new lines of work.

Hugo Faundes studied culinary arts after being fired from the state-run oil company, PDVSA, for what he said were political reasons.

"Now that I've graduated there's nothing to cook," the Valencia man said with a dark laugh.

Tens of thousands have emigrated, and not just in search of economic opportunities. They flee one of the world's worst violent crime rates and a health care system nearing collapse.

Students have engaged National Guardsmen in the nearly nightly cat-and-mouse street battles since the unrest exploded Feb. 12. They've turned the wealthy Caracas district of Altamira into ground zero, honeycombing its center with debris barricades. But most protesters have been peaceful and few demonstrations have spread to the poorer parts of the capital.

The government the United States of fomenting the unrest and it kicked out three U.S. diplomats last month. That move followed a pattern: The day Chavez died, the government expelled two U.S. military attaches.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry has lamented that his government is being blamed for things he says it never did.

U.S. Rep. Gregory Meeks, a New York Democrat, has long praised Chavez's commitment to improving the lives of Venezuela's poor and attended his funeral. But Meeks planned to sit out the commemoration, saying he was "a little nervous" about events in Venezuela.

"There was always opposition, but when there were demonstrations in the streets in the past I never heard of individuals being killed by anybody in the government," he said. "It gives me real concerns as to where the country is headed."

___

Associated Press writers Christopher Sherman and Ezequiel Abiu Lopez contributed to this report.