North Korean defectors: Mothers who have escaped after suffering forced abortions, sex trafficking, and abandoning their children speak out

North Korean defector mothers who have suffered forced abortions, sex slavery, and deep psychological torture share their stories with Fox News.

The pain of losing her babies is still evident in the eyes of Kim Jeong Ah, a North Korean defector and mother. The life of the 43-year-old Hermit Kingdom survivor has been scarred by battle after battle, and all she can do now is pick up the pieces.

Three days after Jeong Ah was born, she was orphaned. Her adoptive mother and father were dead by the time she was 13 and, soon after being adopted at the age of 17, she was summoned to join the North Korean military. After narrowly escaping death as a result of extreme malnutrition and harsh treatment during her seven-year tenure as a soldier, Jeong Ah thought getting married and starting a family of her own would be the start of a brighter life.

But pain found her at home, too.

“My first child was born without any issues, but while pregnant with my second child, when I was seven months pregnant, my husband, who was physically abusive, due to his beatings, my daughter was born with a disability,” Jeong Ah told Fox News. “Unfortunately, my second child did not survive for more than 10 months, and I realized I could not stay in this type of environment. But I had nowhere to go, no extended family because I was [an] orphan, so I decided to escape North Korea.”

NORTH KOREA'S FORCED ABORTIONS: THE HERMIT KINGDOM'S UNDERREPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES

Men are conscripted into the North Korean military starting at 17 years old, while females undergo selective conscription. Only those from the ranks of the political elite and families of the ruling class are exempt. Conscription is one of the key reasons many still opt for the dangerous journey of escaping their native land, risking not only North Korean capture and retribution but the potential to be locked away in some anonymous Chinese border prison.

Kim Jeong Ah (left) and Son Myunghee (right) are defectors from North Korea and now part of the NGO Tongil Mom, based in South Korea, advocating for mothers forced to leave their children behind in North Korea and China. (Hollie McKay/Fox News)

The young mother, who left her eldest child with his father in North Korea, found out she was pregnant soon after crossing into China -- where she had just been sold into “a human trafficking situation.” One of Jeong Ah’s customers agreed to be her “husband” to avoid the immediate threat of having her be forcibly returned to North Korea.

“But for almost two years and nine months, I lived in fear of being arrested and forced back to North Korea, so I knew I had to go to South Korea,” she said. “After resettlement, I wanted to bring my Chinese husband and daughter I had with him, but he refused. For ten years now, I have not been able to contact my daughter in China, or hear her voice, or know what is going on in her life.”

North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un is seen in the above photo released by the reclusive regime. (Reuters)

After entering South Korea, a decade ago, Jeong Ah has gone on to serve as founder and executive director of Tongil Mom – which translates to Unification Mom. The NGO focuses on issues related to the mental health and wellbeing of defector mothers. Jeong Ah is one of the thousands of defectors grappling with the tragedy of her plight and, even though she is remarried to a South Korean man and has a son with him, barely a moment goes by in which Jeong Ah doesn’t think of her two estranged children and the baby who died in such harrowing circumstances.

“I gave birth to four children, but, tragically, I only have one child that I am living with. Looking back, I feel that I was abandoned by my own birth parents, and I feel so terrible that I myself did the same thing my parents did to me,” Jeong Ah said. “I feel a great sense of tragedy and sadness that I have done this to my children. That Is part of the reason I started this organization, to deal with the hurt and the pain so many other defector women go through in forced separation.”

The Ministry of Unification estimates that, as of June 2019, some 33,022 North Korean defectors had entered South Korea, of which 23,786 – about 72 percent – were female. That trend has increased throughout 2019, in which the female defectors going from the North to the South accounted for 85 percent of the total defector population.

Forced repatriation from China to North Korea has many defector mothers living in a cycle of never-ending fear. (Tongil Mom)

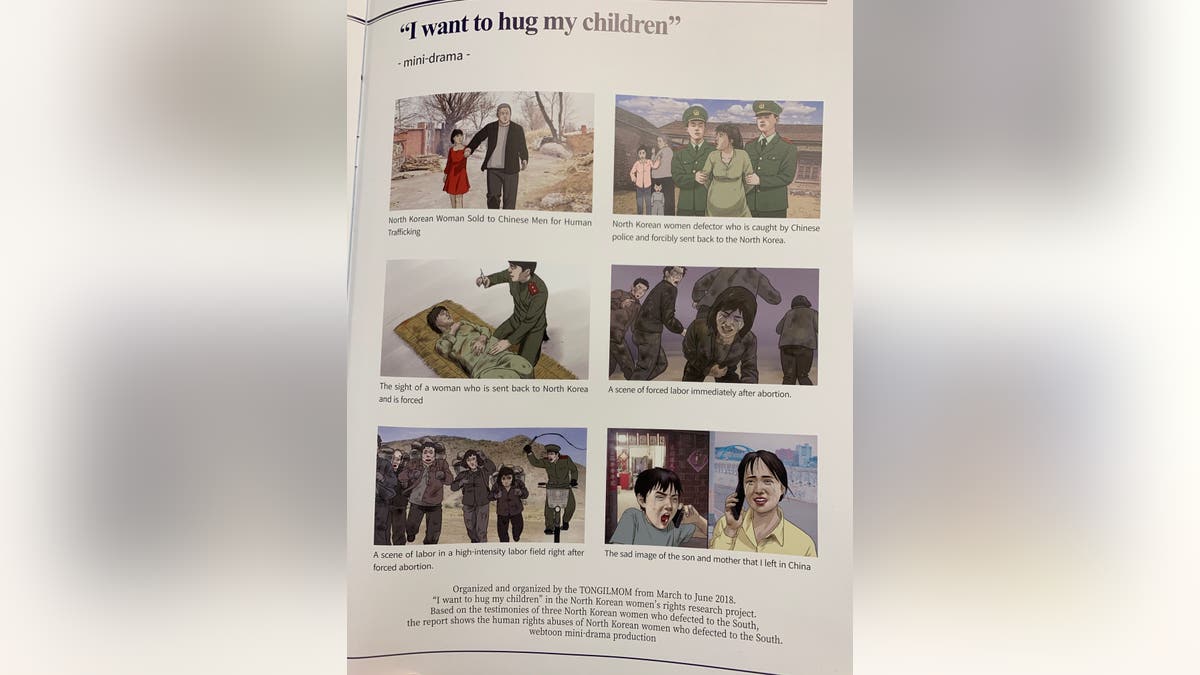

Data indicates that 17,566 North Korean female defectors are in the age range of 20-40, with the vast majority mothers who have had to leave their children behind as they attempt to make money and carve out a way to survive. During the process of fleeing their impoverished home country, many women are forced into sex and labor trafficking, often are sold to Chinese men and ultimately forced to marry.

“However, the Chinese government does not give North Koreans Chinese citizenship and [treats] North Korean defectors as illegal border crossers,” the latest Tongil Mom report, “I Want to Hug My Child,” states. “They even send them back to North Korea by force. As a result, female North Korean defectors should live with uncertain status and the fear of suddenly being caught and sent back to North Korea by force, although they have a family.”

Defectors thus live every moment with the risk of being discovered and forcibly returned to North Korea. If pregnant, the defectors also face the threat of a forced abortion on return. The looming fear and routinely brutal living conditions in China propels many women to flee their children and families once again and relocate to South Korea.

"I Want to Hug My Child" is the latest report by North Korean defector mothers, which indicates that the overwhelming majority of defectors are women. (Tongil Mom)

The women who make up the leadership of Tongil Mom are tireless in their push to highlight the ongoing human rights violations suffered by female North Koreans both in their homeland and as defectors in neighboring China, and are urging the international community to support the defectors even after they have left North Korea.

SYRIAN REGIME ACCUSED OF DOZENS OF TORTURE METHODS FROM 'CRUCIFIXION' TO RAPE TO EYE-GOUGING

“We want to raise awareness about the North Korean defector women and what they experience. Once they resettle in South Korea, it doesn’t mean the nightmare ends for them,” said Son Myunghee, 35. “The forced repatriation policy [in China] obviously hurts the North Korean defectors, but it hurts their own citizens too. Chinese fathers are then forced to raise the children on their own.”

Myunghee was also given up for adoption the day after she was born. Her adopted parents died when she was young, forcing her to work in an illegal scrap metal mine near her home town.

“The regime tried to make an example out of me and use me to put fear in the population. I had to escape this whole situation of further mistreatment and punishment,” she said.

Defectors thus live moment by moment with the risk of being discovered and forcibly returned to North Korea. If pregnant, the defectors also face the threat of forced abortion on return. The looming fear and routinely brutal living conditions in China then propels women to flee their children and families once again and relocate to South Korea. (Tongil Mom)

Myunghee first escaped North Korea in 2007 after two years of hiding in the mountains, but her foray into “freedom” was short-lived. In 2012, she was kidnapped and repatriated. Myunghee was tortured so severely by Chinese agents, she said, that her intestines ruptured and she was left fighting for her life before being returned.

Myunghee absconded again in 2014, making it to South Korea the following year. She currently lives in South Korea with her Chinese husband and children, and endeavors to support other victims of forced repatriation.

Another defector, who requested anonymity given that her immediate family remains in North Korea, told Fox News that, since defecting in 2004, she is only able to afford to speak to her children once per year. Arrangements are made through a secret broker that goes to the family home in North Korea and uses a Chinese cell signal to facilitate a brief phone call.

It’s a few minutes of joy, eclipsed mostly by waiting and agony.

“I have met many defectors, and whether they have been settled in South Korea for one year or ten years, they all suffer from PTSD and require treatment. The type of PTSD and trauma they are suffering from prevents them from living properly in a life of freedom,” explained Oh Eun Kyung, the director of Tongil Mom, a counseling psychologist supervisor and professor at the Korea National University of Transportation. “Instead of seeking help; they turn to alcohol or suffer from deep depression and anxiety.”

Kyung is urging defector women not to be afraid to step forward and join Tongil Mom’s group sessions – attended by hundreds of women across South Korea.

Oh Eun Kyung, the director of Tongil Mom and a counseling psychologist (Hollie McKay/Fox News)

“We want to provide a safe environment for these women to come and experience this type of counseling. What these defector women have suffered through is unspeakable, and the first step is to provide a place for them slowly to open up to people they can trust and start revealing what they went through,” she said. “The pain can’t be erased, but there are people willing to help. And that is the only way they can grow and live in freedom.”