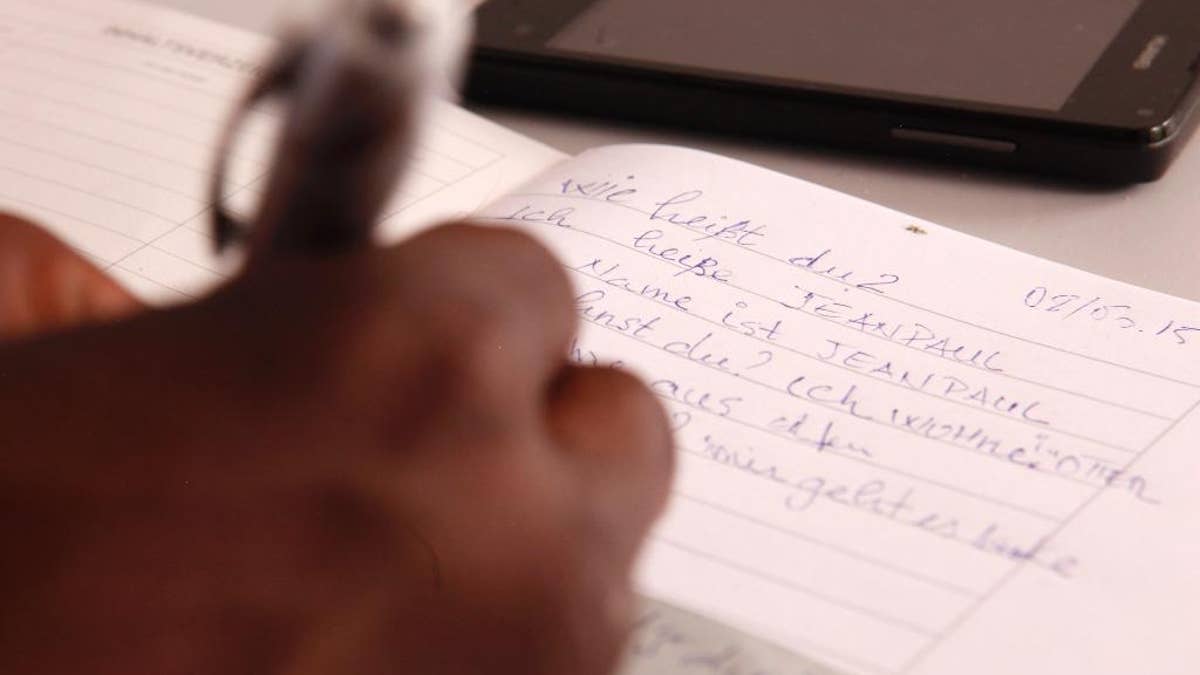

In this June 13, 2015 photo Jean Paul Apetey practices German in an asylum seeker shelter in Otter, northern Germany. Apetey enjoyed a well-organized, warm arrival in the north German state of Lower Saxony. (AP Photo/Dalton Bennett) (The Associated Press)

CREIL, France – Against the odds, Hamed Kouyate has achieved his childhood dream of escaping African poverty and reaching the wealthy heart of Europe. But like many fellow migrants who endured a clandestine odyssey marked by toil and terror, the teenager now questions whether he's just gambled his life on a cruel illusion.

"Europe has no gold or diamonds for me. I've had to sleep rough and go without food for days since arriving in France. Nothing has been as I thought it would be," the 18-year-old says as he walks along the riverbank in the Parisian suburb of Creil, three years of travel and more than 5,000 meandering miles (8,000 kilometers) from his Ivory Coast home. "I regret leaving Africa. I would not recommend this route even to my worst enemy."

Since January, The Associated Press has followed a 45-member group of West Africans as they traveled by foot and cramped smugglers' vehicles from Greece to Hungary via the Balkans. The route, accessed from a Turkey clogged with refugees fleeing Islamic State barbarism, is already the second-most popular way to gain illegal entry to the 28-nation European Union and its two biggest destinations: Germany and France. Unprecedented waves of Asian, Arab and African migrants are taking the slow, grueling route in preference to a sea crossing from North Africa, the quicker but reckless path to Italy. Thousands making that journey have drowned in the Mediterranean over the past year.

Kouyate and several other migrants interviewed by the AP have documented the Balkans' own risks: deadly night trains that crush trekkers trapped on ridges, bridges and inside tunnels; robberies by criminal gangs and corrupt police lingering like vultures along the route; smugglers who hold their own clients hostage, raping women and beating men, until distant relatives wire extra cash; staggering hunger and thirst as hikes expected to take days stretch into weeks.

That trauma was all supposed to be worth it, the travelers kept telling themselves with each brutal setback. By April they finally reached Hungary, from which they could travel by jitney cabs and public transport links within the largely passport-free EU to Germany and France. The vast majority of the West Africans reached their destinations by May, having paid a series of Asian and African smugglers more than 5,000 euros ($5,500) to cover every link in the chain from Turkey to the EU's eastern frontier.

While Germany has proven to be comparatively generous to arrivals, France is posing a tougher test. Neither permits the asylum-seekers to work while their cases are under review, but Germany gives the newcomers often high-quality housing in bucolic suburban settings along with monthly payments in the low three figures. Kouyate, by contrast, says he has received a single 40 euro ($45) payment in France, where he has bounced from sofa to bedsit to park bench and back again.

Germany received 202,834 asylum-seekers in 2014 — nearly a third of the EU total — and expects to double that figure to reach another record high this year. Chancellor Angela Merkel has publicly committed to doubling federal government spending on asylum-seeker support and pledged an extra 1 billion euros this month to state and local authorities to ensure all newcomers have housing and can pursue German language education, mandatory for achieving residency.

It's a starkly different picture in France, which already has accepted more than 250,000 foreigners as refugees — many of them French speakers from former colonial possessions such as Ivory Coast — and last year received another 101,895 asylum applicants, second-most in the EU, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The French Office for Protection of Refugees and Expatriates is able to house only a third of new applicants directly, while many sleep outdoors, in train stations or tent shantytowns.

The waiting for state accommodation can typically last a year — by which time migrants already have lost their court cases and exhausted their right to stay.

France's immigration tribunals now are accepting less than a fifth of applicants. They favor candidates from active war zones such as Syria, not economic migrants from impoverished but relatively peaceful Ivory Coast, where a decade of bloody coups and civil war has abated since 2011.

The prospect of rejection has yet to sink in for Kouyate. He handed himself twice to police before getting a referral to child protection authorities, who helped him secure a state-funded spot in a youth hostel. He now hopes to win a job as a professional soccer player, a seemingly pie-in-the-sky ambition given that he failed to achieve this goal in less-competitive Turkey. He's already been rebuffed by a few French clubs who said they couldn't consider giving him a trial without proper residency documentation.

Kouyate, undaunted, appears to be disenchanted with everything about France except the football.

"Soccer is my passion. It's because of soccer that I'm in Europe. In September I'm going to train with a team," he said, noting he currently lacks studded soccer boots.

"The hostel will buy me soccer boots and they'll register me with a team," he insisted.

Around 500 miles (800 kilometers) to the northeast, his Ivorian travel mates Jean Paul Apetey and Hilarion Charlemagne have enjoyed a well-organized, warm arrival in the north German state of Lower Saxony. Unlike Kouyate, they are much happier with their state-provided surroundings in farming towns south of Hamburg, where fields of strawberries and white asparagus dominate the landscape. Both are focused on learning enough German quickly to demonstrate their earnestness and impress their hosts, to win residency and start to earn cash that they can wire home to their children.

Charlemagne held up the crumbling pair of shoes he has worn since Greece, including on more than two weeks of police-interrupted hikes through Macedonia. "I won't be needing these shoes much longer," said the 45-year-old teacher.

German authorities have placed him and three other West African migrants in a newly refurbished, two-apartment residence in the town of Brietlingen, population 3,400. The neighbors, an elderly German couple, don't speak French or know where Ivory Coast is. Charlemagne calls the 70-something woman "Oma," German for grandma.

The woman, who didn't want to be named, said her family fled their native Poland in 1945 as the Russians closed in, so she relates to the Africans' "feeling of the unknown" as newcomers.

Charlemagne and Apetey, a 34-year-old former Ivorian soldier, each receive around 140 euros ($157) a month to cover expenses, and those benefits could rise next month to more than 300 euros ($335) monthly.

Apetey has been placed in a refurbished former hotel in the center of Otter, a village of barely 1,500 residents, some of whom had never seen an African face in the flesh before. The college dorm-style facility opened just three months ago and already houses more than 40 migrants from across Africa and the Middle East.

He shares a room with another Ivorian and two Bosnians, whom he freely admits to distrusting, chiefly because they cannot talk to each other. He suspects a neighboring Libyan of stealing a 20-euro note from his room, but he cannot confront him directly because he doesn't speak Arabic. Most annoying, he says, is the amateur Arab keyboardist down the hall. "He's awful," Apetey declared with a laugh.

Relations with locals are better. In an expression of solidarity, about 20 villagers organized a welcome party in the refugees' new home, bringing cupcakes and board games and rebranding the residence's sprawling living room the "international cafe" for the night.

"You can really never know what they have been through, but I can imagine and I can be compassionate about it," said Maduria Roeper, a 59-year-old lifestyle consultant, Apetey smiling uncomprehendingly at her side. "They definitely must have gone through hard times ... some sort of trauma."

Roeper said some villagers opposed sheltering the foreigners in Otter, but most are determined "to make a bridge for the asylum seekers, to reduce the fear, the barriers ... and really show them from our heart we want to integrate them."

Apetey says he appreciates German hospitality, particularly the informative and friendly approach of police, which he contrasts with every other EU force he's experienced from Greece to Austria. But he fears that his respite from homelessness could be short-lived, that German authorities could dismiss his case for refugee status. This already has happened to Ivorian friends pursuing appeals against deportation orders. He notes that his temporary residence card has an expiry date of just three months.

"I know people who went on the same journey as me, who got the card and three months later, they received a letter saying they have to leave Germany," he said. "We are asylum seekers. We don't have anything! I don't have any contacts. I appeal to whom? With what money? You get a lawyer, that's money."

In France, Kouyate suggests that part of him wouldn't mind going back home. He says Africans enjoy a happier environment and greater social solidarity, and contrasts that with the many times he's seen Europeans walk callously past street beggars.

But Kouyate says he must remain resolute and make a European success of himself, because his parents have sacrificed many thousands in cash payments to smugglers and soccer agents. He doesn't want their investment to be in vain.

"It's not a debt exactly. It's about pride," he said. "When parents spend so much to send their child to Europe, it's rare that the child shies from the challenge ... so I can't just go back."

___

Pogatchnik reported from Dublin. Associated Press reporters Raphael Satter in Istanbul and Kirsten Grieshaber in Berlin contributed to this report.