Lost boys: Yazidis fear boys brainwashed by ISIS will never heal

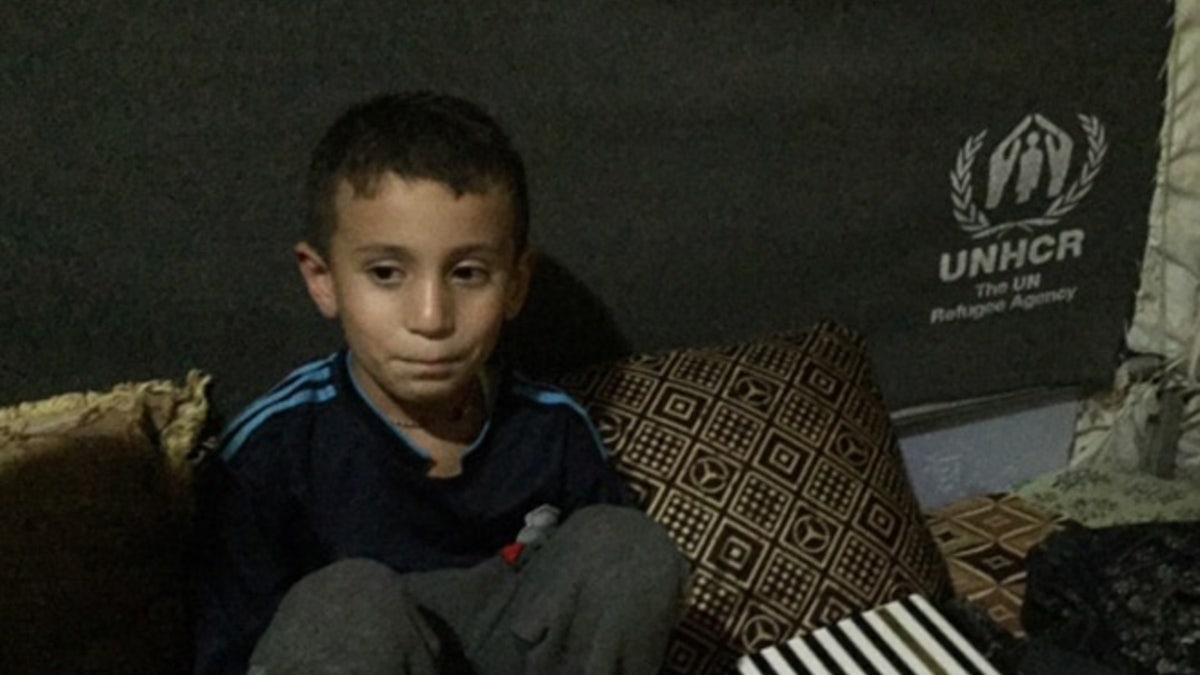

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}A driving storm had just swept through a sprawling refugee camp in the small Iraqi-Kurdistan border town of Zakho, and while the other children his age squealed as they played in the puddles outside, 8-year-old Zed sat with his back against his family's tent wall, arms folded, eyes angry.

"We are trying to convert him back to Yazidi,” his mother, Seve, told FoxNews.com. “But sometimes he does not agree. When he gets angry, he recites verses from the Koran.

Zed is still confused and angry from his time as a so-called "caliphate cub." (FoxNews.com)

"And he yells we should never have escaped, we should never have come back here," she added.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Zed’s entire family, including his mother, father and three sisters, were ambushed and captured by ISIS while fleeing the terror army as it overran their village near Sinjar two years ago. They were made to convert to Islam, traded at the market for the equivalent of $50, and moved from Mosul to Raqqa. There, Seve was held as a sex slave as her young girls - now between 5 and 10 years old, including one with special needs - looked on, their tiny bodies starved and beaten.

Zed's mother, Seve, holds her daughter, 5-year-old Iman. (FoxNews.com)

Seve’s husband has not been heard from since. Zed was forced into a "caliphate cubs" jihadist training camp.

"They were breaking his teeth every day, his teeth are all broken. They took him to training and were making him use a large weapon for three to four hours a day," Seve said. "Only, he was too small. He couldn't hold the weapon, let alone shoot it. Eventually they brought him back to me. But normally, those children are never coming back."

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}She doesn't know how long her family was in the grip of ISIS, her recollection dulled by the fear and hopelessness of the ordeal.

Zed is not the only one whose brainwashing remains effective. Many of the returnees still adhere to the Muslim call to prayer when it chimes from a nearby mosque. Many forget what it means to be Yazidi. And many are extremely violent toward their loved ones.

Ahmed is faring better since being rescued from ISIS, and drew an "X" through this picture. (FoxNews.com)

"He beats his siblings," Seve continued, as her silent son fidgeted and slumped in the corner.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}With the assistance of smugglers and a network of rescuers, the family finally made it out of Syria and to the relative safety of the camp on June 2. They are now safe, but the family may never be whole again.

For every Yazidi in Iraq, life is made up of two parts. There is the quiet, peaceful farming life in mountain villages before Aug. 3, 2014, and then there is the lesser life from that day on - the day the genocide of their ancient religion at the fist of ISIS systematically started.

Their men are missing and in many cases, presumed dead. Their women have endured the unspeakable degradation of sexual slavery. There homes have been destroyed. And many children of this ancient faith which predates Islam and Christianity, have become terrorists, weaponized against the people they once loved, and who still love them.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}The Yazidi boys were turned against their own by twisted training regimes that included Islamist indoctrination, weapons instruction and classes on the finer points of beheading and becoming suicide bombers and human shields.

Now housed in camps, their homes sacked and destroyed, the peaceful, traditional community is trying to heal with next to no help.

"Psychologically, they are hurting. They have been influenced a lot, especially the young boys [ages] four to five," said Hussein Al-Qaidy, director of the Office of Kidnapped Affairs, which operates under the Kurdish Regional Government's Prime Minister's Office. "They forget how to speak Kurdish. Some still insist on praying five times a day. Many no longer have fathers and mothers. This is a difficult thing."

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}According to Al-Qaidy, they formerly had a few basic program agreements with European non-governmental organizations for help in de-radicalization. But funding has dried up, and this devastated, endangered ethnic populace is broken and largely on its own.

As it stands, there are just over 700 children who have been rescued or fled ISIS camps, with thousands still missing. According to one Kurdish official, ISIS operatives have been busy shuffling many of these boys to Raqqa in recent days as Iraqi forces move into Mosul. But, Al-Qaidy said, many of these minors are being executed or used as cannon fodder by the brutal terrorists.

Al-Qaidy’s office, a cement building nearby in Duhok's city center, is the hub of functions in the war with ISIS that is as somber as it is necessary. People, mostly Yazidi, float through the tiny waiting room looking for news on their loved ones, their eyes haunting and desperate.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}One aging man, dressed in his finest suit, pulls out his phone and starts showing us photographs of smiling children. All eight have been missing since ISIS marauded through their village three summers ago. Another man, in farmer’s trousers, stares out into the desert sunshine - nervously pulling at strands of hair.

At the office, a rescued boy named Ahmed, who is 16, but looks no older than 12, lifts his shirt. It has been more than 18 months since he and his little brother escaped the jihadist bivouac, walking days in the sweltering Iraq heat and finally reaching safety, and yet his ribs are still raw and blue from the daily lashings.

The timid, gentle teen drew a picture for FoxNews.com. In black ink, it showed an ISIS member holding up the jihadist flag. Switching to a red pen, he drew a large “X” through it. But Ahmed is a rare exception – a teenage Yazidi boy who made it through ISIS captivity with his heritage intact.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}These young, conscripted jihadists pose a real threat to their friends and families, yet community leaders are firm in welcoming them back. They hope more boys will return after the liberation of Mosul and then Raqqa, ISIS’ Syrian stronghold. Time, and the embrace of their people, will heal the boys, they believe.

"These children are victims, what happened to them was not their fault," Al-Qaidy said.

Baba Chawish, a leading Yazidi spiritual authority and guardian of their holiest site, Lalish, has repeatedly called for the community not to ostracize the returnees, and ensure they are embraced.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}However, the sense of helplessness is at times overwhelming.

"As a community we don't have a problem accepting them back," says Col. Marwan Sabri, who heads the Peshmerga Yazidi brigade in the Northern Iraq area. "But we have no experience in this and no resources to help. We don't know how to help them."

A senior Kurdish intelligence official told FoxNews.com that returning Yazidi boys won't face repercussions despite what they may been made do in the service of ISIS. But the official expressed concern that de-radicalization and psychological help is pivotal.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Atop the barren Sinjar Mountain, where thousands of Yazidis fled amid the ISIS assault and subsequently died of dehydration in the scorch of summer, a 36-year-old Syrian Kurdish nurse named Khansa Ali - a refugee herself from Rojava - is doing her best to save children, working out of a shoebox clinic with a few medicine bottles and beds.

"Psychological problems are the number one thing. They come here - broken and in shock," Ali, who locals call a "hero doctor," said from the clinic, where she lives. "But all we can do is try to sit with them. Talk to them."

And down in the masticated streets of the mountain foot village of Snoni, once occupied by ISIS, local school teachers are encountering similar frustrations. Depression, isolation, fear, says 6th grade teacher Hadi Mured, are just a few of the symptoms plaguing the survivors.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Professional and long-term psychological and de-radicalization programs, experts agree, are desperately needed.

"Many have been forced to kill, and they are now desensitized to killing," said Dr. Anne Speckhard, adjunct associate professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine and director of the International Center for Violent Extremism.

"They will need programs similar to other forcibly conscripted child soldiers. PTSD and deprogramming-type therapy will be needed intensively at the beginning. They will need to be restored to safety and security to be able to participate in therapy in a meaningful way."

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}That, she noted, is particularly challenging, given that many have lost their family to the genocide.

"But this can be treated," Speckhard said.

As a FoxNews.com reporter rose to leave the humble canvas home, Zed, who has just started first grade at the camp, suddenly - as if slowly warming back to life - had something to say.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Today, he learned the English alphabet, he said. And he wanted to practice it.