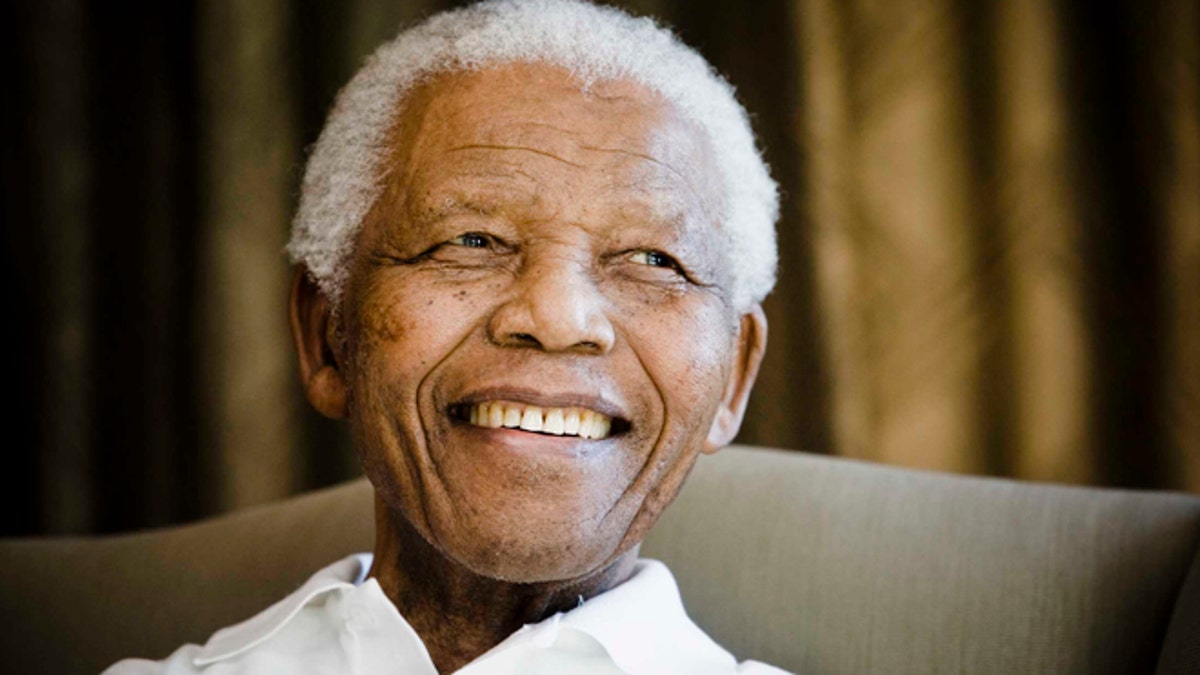

June 2, 2009: Former South African President Nelson Mandela reacts at the Mandela foundation, in Johannesburg, South Africa, during a meeting with a group of American and South African students as part of a series of activities leading to Mandela Day on July 18th. (AP)

JERUSALEM – Israel's state archives has published a 50-year-old letter from the Mossad spy agency claiming it unknowingly offered paramilitary training to a young Nelson Mandela, along with documents illustrating the Jewish state's sympathy for the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1960s.

The release of the documents on the archives' website in the wake of Mandela's death appear to be aimed at blunting criticism of the close alliance Israel later developed with South Africa's apartheid rulers.

Israeli relations with post-apartheid South Africa remain cool. The South African government is a fervent supporter of the Palestinian cause, and the Palestinians frequently compare their campaign for independence to the black struggle that ended apartheid.

Early this month, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was conspicuously absent from the dozens of world leaders, including President Barack Obama, who attended Mandela's funeral. In a decision that was widely criticized, the globe-trotting Netanyahu cited the high cost of chartering a plane and bringing a large security detail.

The newly published Israeli documents from the 1960s, released days after Mandela's death on Dec. 5, highlight Israeli officials' voices against apartheid and their attempts to rally international pressure on the South African government to stop the 1964 Rivonia Trial, in which Mandela would be sentenced to life in prison.

But perhaps most startling is the memo, first revealed by the Haaretz daily over the weekend, claiming Mandela received paramilitary training from Israeli handlers in Ethiopia in mid-1962 — without them realizing who he was.

In the 1960s, Israel actively courted Africa's post-colonial leaders in a search for allies. It sent scientists and other experts across the continent — and the memo suggests that it was running a military training program for fighters, though it is unclear the scope of the program. After the 1973 Mideast war, when under Arab pressure dozens of African countries broke diplomatic ties with Israel, the Jewish state formed close military ties with South Africa's apartheid government.

The Oct. 11, 1962 memo, labeled "Top Secret," suggests the Israeli trainers thought the man they later discovered was Mandela was from Rhodesia — now Zimbabwe — where African nationalists at the time were struggling against colonial rule.

According to the memo, a man named "David Mobsari who came from Rhodesia" met with officials several months earlier at the Israeli Embassy in Ethiopia, expressing interest in the tactics of the Hagana, the pre-Israel Jewish resistance movement against British rulers.

"He greeted our men with 'Shalom,' was familiar with the problems of Jewry and of Israel and gave the impression of being an intellectual," the letter says. He received training in judo, sabotage and light weapons, it said, adding that the "Ethiopians" — an apparent code name for Mossad agents there — "tried to make him into a Zionist."

Only after Mandela was arrested and his picture published did the Israelis determine his true identity, the letter says, referring to him as the "Black Pimpernel," a widely used moniker at the time.

"It now is clear, through photographs published in the media on the arrest in South Africa of the 'Black Pimpernel' that the trainee from Rhodesia introduced himself with an alias and that the two are the same," the letter says. In handwritten notes scribbled on the letter 13 days later, it says his real name is "Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela."

The Nelson Mandela Foundation, an official organization dedicated to promoting his legacy, has questioned the account. While confirming that Mandela toured African countries that year, and even received military training in Ethiopia, it said there was no evidence that he had any contact with Israelis.

"In 2009, the Nelson Mandela Foundation's senior researcher traveled to Ethiopia and interviewed the surviving men who assisted in Mandela's training — no evidence emerged of an Israeli connection," it said.

The national archives posted the letter Sunday following the report in Haaretz, which said it obtained the document from a former graduate student. The ex-student, David Fachler, said he found the letter while conducting research a decade ago and showed it to the newspaper after Mandela's death.

According to other documents released by the archives, Israel maintained a strong interest in Mandela's well-being after his arrest and throughout the Rivonia Trial, where he was convicted of sabotage in 1964 and sentenced to life in prison.

According to the archives, Israel also had an interest in the case because about one third of the defendants were Jewish, and Israel feared the case could spread anti-Semitism in South Africa.

One letter, dated April 21, 1964 and written by Azriel Harel, an Israeli diplomat in South Africa at the time, called for rallying international opinion to prevent the Rivonia defendants from receiving death sentences. He also suggested that an economic boycott of South Africa be considered.

"Perhaps the economic value of the boycott is little, but its psychological or publicity value is high, one that strongly affects public opinion, and that is the way that maybe should be continued, in addition to all the rest of the means to force South Africa to retreat from its racist policy," he wrote.

A Foreign Ministry document dated May 18, 1964, discusses efforts to recruit Jewish philosopher Martin Buber and Israeli author Haim Hazaz to sign a declaration in support of the Rivonia defendants.

The letter, published in English two days later, calls on South Africa to release them, saying, "Shed not the blood of men and women who seek only to hold up their heads in dignity."

Another document includes comments in the Israeli parliament by then-Foreign Minister Golda Meir voicing her objections to apartheid. Another letter written by Harel in March 1965 laments the plight of Mandela's wife, Winnie, after her husband is imprisoned and she is placed under heavy restrictions.

"Her family's source of income has been deprived," Harel wrote. "It is advisable to spread this information and provide means of income for her and her children."

Alon Liel, who served as Israel's ambassador to South Africa in the early 1990s after Mandela's release from prison, said Israel's courtship of African leaders in the 1960s is well known. He said the young Jewish state was in search of allies. "Also, there was a policy that Israel will be a light onto the nations," he said.

Yaacov Lozowick, Israel's state archivist, said there was no political agenda behind the publication of the documents. He said the archives often publicize documents that may be "interesting" in connection to current events, such as Mandela's death.

But he said it was possible that staffers were aware of Israel's strained relations with South Africa and searched for something more positive.

"I didn't ask them. They didn't ask me. But it's very likely. Yes. That's human nature. But was it damage control from the prime minister's office? Definitely not."