Colombia’s peace agreement bloodied by distrust, drugs and the Venezuelan regime

Colombia’s peace agreement with the Marxist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels is on feeble ground amid a deepening humanitarian crisis, drug trafficking and distrust between opposition groups.

BOGOTA, Colombia – The monumental, Nobel-winning 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Marxist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels was saluted as a historic victory for international diplomacy – a declaration meant to end the civil war that had bloodied the nation for more than 50 years, claimed the lives of more than 200,000, and displaced more than seven million from their homes.

But with a potent influx of instability from neighboring Venezuela and its own internal struggles, Colombia’s peace process with FARC is on increasingly feeble ground, while hopes to ink a similar deal with the smaller guerilla outfit National Liberation Army (ELN) as the next step in the operation have all but vanquished.

“Fifty years of civil war cannot be resolved only by a handshake and a Nobel Prize. Maybe the rush to find an agreement, due to international pressure, has not had the desired effect,” Silvio Mellara, the Colombian legal representative for the Italy-founded, humanitarian foundation Perigo – which operates in some of the most volatile parts of Colombia – told Fox News. “We can’t talk yet of post-conflict.”

Mellara explained they are seeing whole communities being forced again into displacement, due to a rise in violent clashes between guerrillas and paramilitaries.

Juan de Jesus Arias, 52, fled from his home in Putumayo to the capital Bogota in early December after two of his teen daughters were targeted and killed by rebels. He said no side can be trusted not to break rules.

“I have lost 18 members of my family in this war,” Arias, who said he was simply a poor land caretaker who was caught in the conflict crossfire after the landowners failed to pay “tax money” to the groups operating in the area, lamented. “No one has done anything to help. There is no justice, no real peace.”

Juan de Jesus Arias, 52, fled from his home in Putumayo to the capital Bogota in early December after two of his teen daughters were targeted and killed by rebels. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

Aid agencies operating in Latin America have also recorded an uptick in Colombians fleeing their homes in response to the violence.

Sabrina Lustgarten, Director of the Jewish-American refugee aid organization, HIAS, in Ecuador, noted that in addition to the Venezuelan exodus they are seeing around 200 Colombians per months entering neighboring Ecuador. UNHCR’s Representative in Ecuador, María Clara Martín, concurred that the situation has indeed become a “cause for concern” as Colombia’s own predicament has been eclipsed by the Venezuela crisis.

At the heart of the problem, according to many locals, is the resurgence in drug trafficking money-making backed by the Nicolas Maduro-led Venezuelan regime. The drug trade is believed to have benefitted not only from the instability in bordering Venezuela, but have directly profited from it.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reported in September that coca production in Colombia had reached an “all-time high” in terms of production, highlighting that the surge could “undermine peacebuilding efforts, weaken the culture of lawfulness, strengthen armed groups and delegitimize democratic institutions through corruption and illicit financial flows.”

Compounding the problem, the Colombian government has had to divert attention from its peace process – including getting the ELN to lay down arms – to manage the exodus from the neighboring nation.

More than three million Venezuelans are estimated to have fled their country since the economic crisis spiraled drastically in 2015. More than one-third of the mixed migrant flow has streamed into neighboring Colombia, with thousands more streaming in on a daily basis as the situation in Venezuela deepens – gripped by hyperinflation, starvation and a dire shortage of food and medical care.

Colombia’s new president, the U.S.-allied conservative Ivan Duque, who took office in August, has criticized the much-hailed peace agreement and vowed to take a much harder stance against the growing of coca crops. Duque has also pointed out Maduro’s close inner-circle props up the mega narco-trafficking ring Cartel de los Soles, which is connected to cartels in Colombia – swelling the instability, violence and criminal activity in Colombia – so that Maduro can deflect from his own disaster and solicit patriotism of his own.

Colombia's President Ivan Duque gives a thumps up to the press during a welcoming ceremony for him at the presidential palace in Panama City, Monday, Sept. 10, 2018. Duque is in Panama on a one-day official visit. (AP Photo/Arnulfo Franco)

Gunshots ring out in the distance, and undeterred young men sneak their way from Venezuela into Colombia from dusk to dawn. It’s called the “irregular passage” and between 700-1,000 are estimated to make the illicit crossing from Venezuela into Colombia every day, clamoring through the thick canopy of jungle and across the Táchira river into the overflowing migrant border area of Cucuta, Colombia through a hole gouged out of a wall.

To cross the river, one has to pay guerillas and paramilitaries who control territory on both sides of the river. And when violet skirmishes break out between those groups, bodies are routinely thrown into the river, and carried away by the current.

Illicit crossing from Venezuela into Colombia (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

The illicit groups, outfitted with small arms, work with middlemen referred to as “bag carriers” to avoid detection. The carriers are ordered to work without a shirt to distinguish themselves from being militia members, and are forbidden to carry identification or a cell phone. They assist with crossing and take the cash, asking no questions. But in the shroud of absolute secrecy, the “bag carriers” says it’s mostly the ELN, in cohorts with FARC dissidents with Venezuela safe haven, making the cross-border money.

384090 01: ***EXCLUSIVE*** Two members of the AUC, the United Self Defense Force of Colombia, the extreme right paramilitary group, patrol a coca leaf plantation where a manual eradication of the coca leaves has gone into effect January 8, 2001 in the province of Putumayo, Colombia. Since the U.S. aid plan for Colombia began last December 15, the AUC are manually destroying coca leaves with machetes in and around the vast areas of coca leaf plantations south of Putumayo. The Colombian leftist guerrilla group, the FARC, is attempting to take control of areas that were under their control, not more than a year ago. (Photo by Piero Pomponi/Newsmakers) ((Photo by Piero Pomponi/Newsmakers))

Colombian intelligence reports released in November concluded the ELN had amplified its capabilities in smuggling, food distribution and illegal mining across Venezuela. The group is estimated to now be present in around 12 states, at least half of Venezuela, according to InSight crime mapping and analysis – expanding from the Colombian border side deep into the neighboring nation where it is said to receive political protection from the increasingly harsh stance of the Duque-led government.

And in some cases, the ELN has even been bold enough to launch attacks against the Venezuelan military and miners – reflecting their burgeoning sense of inside security and power. In early November, the guerrillas killed three officers in the Venezuelan state of Amazonas, in retaliation for the arrest of four ELN members, including a top leader. Venezuela’s Defense Minister decried the presence of any armed group, but did not acknowledge the existence of the ELN as the perpetrators.

IN VENEZUELAN CRISIS, FAMILIES CAN'T EVEN AFFORD TO PROPERLY BURY THE DEAD

According to one high-ranking Colombian intelligence official working closely with the implementation of the peace agreement, there are at least four senior ELN members red-flagged by Interpol – the organization that coordinates international police cooperation – yet are currently receiving protection in Venezuela.

“The Colombian guerrillas are there to give the Venezuelan government strategic backup, they are there in case the government needs them,” said the official, noting that there are at least 2000 ELN members mobilizing in and around the Colombia-Venezuela border area sowing the seeds of instability.

Duque has also mandated not to resume stalled peace talks with the ELN rebels until all hostages in their captivity have been released, and refused to allow Venezuela to continue its role as one of the guarantor countries designated as a neutral player to oversee the talks. His contend he is adding conditions and demands that were not previously agreed by the two sides, and the ELN has so far refused the new conditions that would see peace talks be restarted.

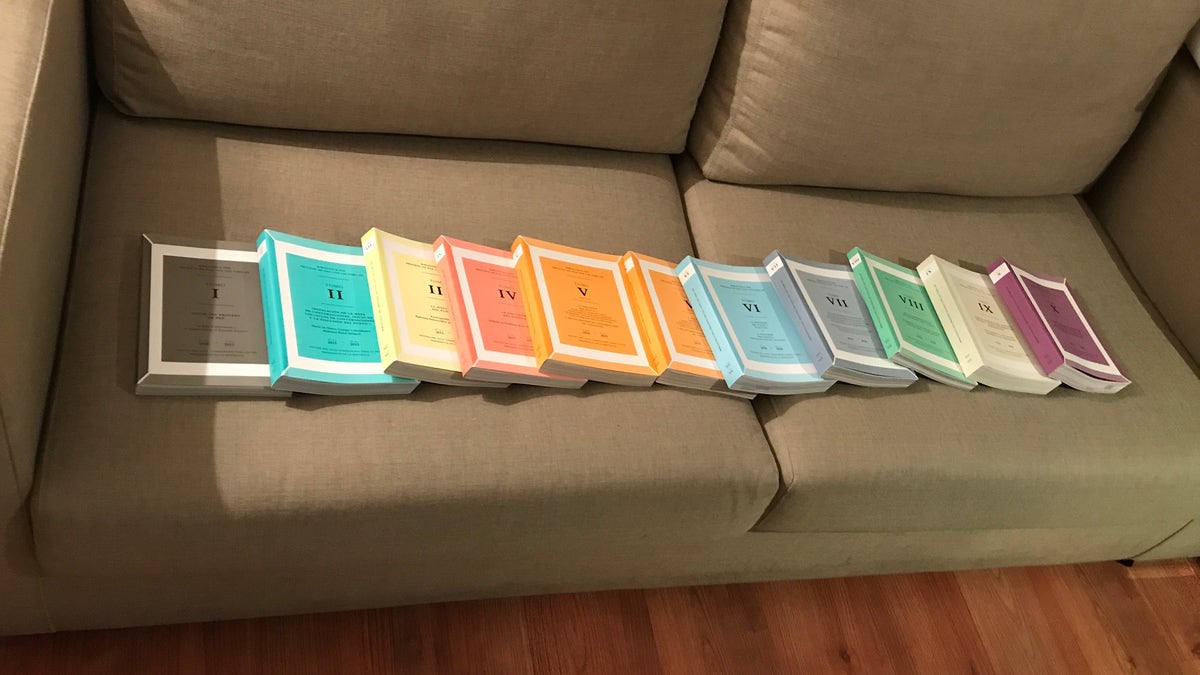

The Nobel Peace Prize-winning, lengthy 2016 Peace Agreement (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

U.S. government officials closely monitoring the situation between Venezuela and Colombia, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, agreed the Venezuelan impasse is fast deteriorating, and has amounted to a real strain on Colombia’s resources, paving the way for “pockets of instability” that could quickly amount to instability in Colombia.

“Peace was supposed to be the focus, but the attention that should have been placed on this has had to be diverted to the challenges of the Venezuelan migrant crisis, and with that comes an increase in illicit economic dealings,” one official observed. “And after the FARC a certain power vacuum has been left, which isn’t helped by the fact that some ELN receives safe harbor in Venezuela.”

Indeed, signs of strain from all fronts are evident.

The reconciliation component of the agreement, arguably the most vital component officially known as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), too suffers from deepening distrust and disillusionment between factions.

“I do not think there has been enough support for the victims, because we have never really been at the center of the agreement,” said Yolanda Perea Mosquera, 34, a human rights defender in the city of Medellin and survivor of sexual violence, forced abortion and the murder of her mother at the hands of the FARC. “Even though we defend the agreement, we do not have enough support and we have many mothers who are now heads of family in a very difficult situation and in my case we do not have a home or a good job. There are many children who have been left without parents or who were victims of sexual violence, recruitment, forced disappearance. This has been very hard for us.”

Yolanda Perea Mosquera, 34, a human rights defender in the city of Medellin and survivor of sexual violence, forced abortion and the murder of her mother at the hands of the FARC. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

But for Bertha Lucia Fries, a survivor of a FARC-orchestrated 2003 El Nogal Club bombing in Bogota that left her with several shattered vertabrae, said her healing has come from forging reconciliation “workshops” between victims and rebels. She went on to be a representative for those who were once her enemies during peace negotiations in Havana.

“I always explain I went to hell, I have a post-graduate in hell,” Fries said, underscoring the importance of maintaining the commitment to the agreement and expressing her fear of government withdrawal given that “war is always going to be more profitable than peace.”

Fries contends the 2016 agreement was an extremely sophisticated document, developed by some of the world’s most experienced expert minds in post-conflict resolution, and that she has come to see many of the guerrilla members as war victims too.

“Forgiveness is a personal process, but reconciliation is interactive. This has nothing to do with politics,” she continued, stressing that the Venezuela situation is not sufficient cause to deter the government from its commitment to peace.

Bertha Lucia Fries, a survivor of the 2003 El Nogal Club bombing in Bogota. Her healing has come from forging reconciliation “workshops” between victims and rebels.

And as a wincing reminder of the war not yet over, landmines remain littered across much of the infected nation. More than 11,000 people have been a casualty of those war remnants in Colombia over the decade, some 2,300 of those struck left dead. The number of killed or wounded tripled in 2018 alone to 180 – compared to 56 in 2017 as recorded by monitoring group Colombian Campaign Against Landmines.

On the streets of Bogota, the mere mention of the peace process is met with both praise and pessimism.

“I don’t think there will ever be total peace, but many of these violent groups that have hurt this country so much have started demobilizing,” noted Juan, a 40-year-old artist and jewelry maker. “I remember when we couldn’t walk the streets – when there were bombs exploding under the cars – we have come a long way.”

"I don’t think there will ever be total peace, but many of these violent groups that have hurt this country so much have started demobilizing,” noted Juan, a 40-year-old artist and jewelry maker. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

Meanwhile, 29-year-old seamstress Cindy Martinez advocated things had changed for the better “70 percent,” yet over-zealous government crackdowns and constant fines for street-selling their artisan goods had made it impossible for any to rebuild their lives.

“I worry we are going to have a lot of trouble with our new government, it doesn’t seem as though they really believe in the ideals of peace,” said Angelica Toro, 20, a university student. “I do think peace is possible but we as young people are going to have to do our best to make it hold.”

Colombian university student Angelica Toro, 20. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

Others are somewhat more fatalistic.

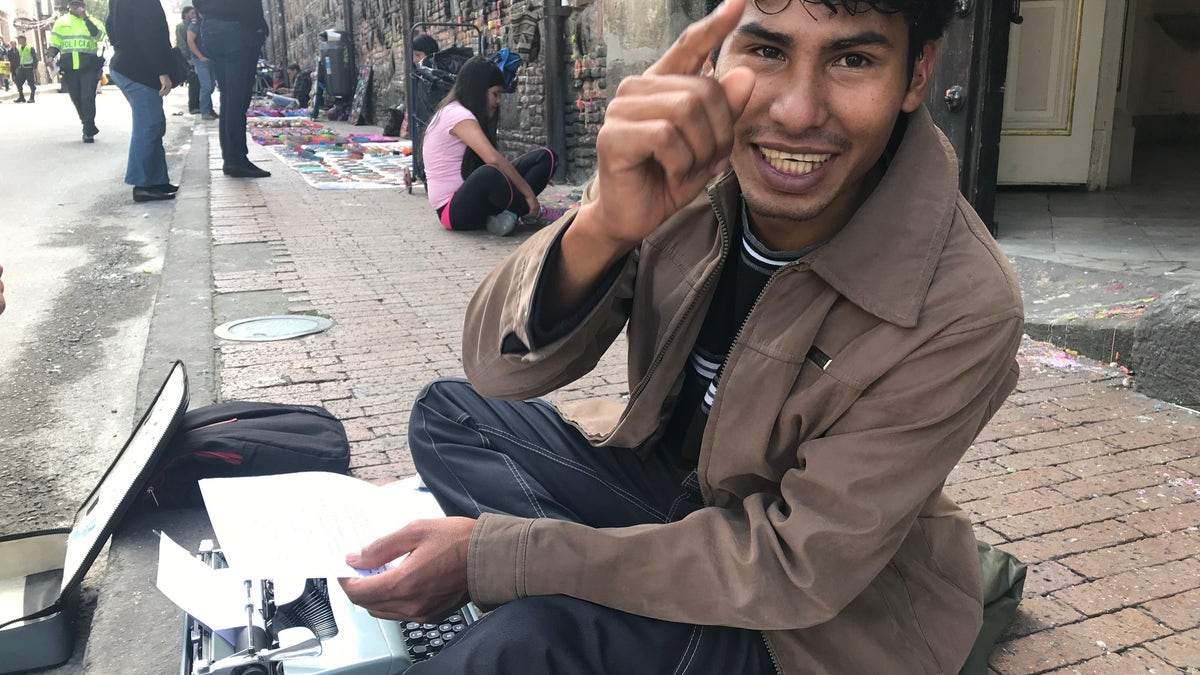

“All they have done is created a document that incites people to think about new ways to deal with old problems,” added Jesus Espicaza, a 27-year-old Bogota poet. “I don’t feel more secure. The fact there is a peace deal doesn’t really mean that there is peace.”

Jesus Espicaza, a 27-year-old Bogota poet (Fox News/Hollie McKay)