Omran Daqneesh sits in an ambulance after being pulled out of a building hit by an airstrike in Aleppo, Syria on Aug. 17, 2016. (Mahmoud Raslan)

Every war bears a human face, and last August the face of Syria’s war became that of Omran Daqneesh – bloody cheeks, covered in debris, eyes wide with shock and his tiny slumped frame in an orange ambulance seat. It’s an image that woke up the world. At just 5 years old, Omran became the symbol for civilian suffering in a war older than he is.

The young boy had just been rescued from the rubble, alongside his parents and three siblings, and was being taken to a hospital following an airstrike on his then-rebel-held neighborhood of Qaterji in Aleppo. An hour later that building collapsed. Three days later, his 10-year-old brother Ali died when a bomb struck the street he was playing in.

Today, the Bashar Assad regime has his family under lock and key, according to photojournalist and opposition activist Mahmoud Raslan, who snapped that haunting portrait of Omran.

Syrian activist and photographer, Mahmoud Raslan

“I lost contact with the family of Omran when we were forced out of Aleppo last year. The Assad militia had arrived and his family was guarded under house arrest where they could not be reached by the Western media,” the 29-year-old photographer – who gave up his profession as a pastry chef to document the conflict that started in early 2011 – told Fox News. “Their residence was changed and they were put under security.”

Raslan, whose claims could not be independently verified, said that his last communication with a relative of the family was in February and that this relative affirmed the family remained under house arrest. Raslan said he has not been able to reach that relative in recent weeks. The media appears not to have documented Omran’s whereabouts since the ensuing days after the attack. In December, the Financial Times reported that his whereabouts was unknown.

The photographer explained simply that the Syrian president’s regime does not want the family speaking out. When asked to respond to the photograph weeks later during an interview with Swiss media, President Assad asserted that it was a "forged picture and not a real one." However, an interview with Russia Today, his wife Asma acknowledged the little boy by name and questioned why children in the Alawite village of Zara, which was assaulted by Al-Qaeda linked groups last May, were not afforded the same media attention.

Nonetheless, the sudden attention on the now iconic photograph last year also fast became fodder for theories that the anti-Assad photographer himself fraternized with terrorist factions. But Raslan, who vows that all he wants is freedom from regime oppression, takes such speculation – as well as the phony photo narrative – with a grain of salt.

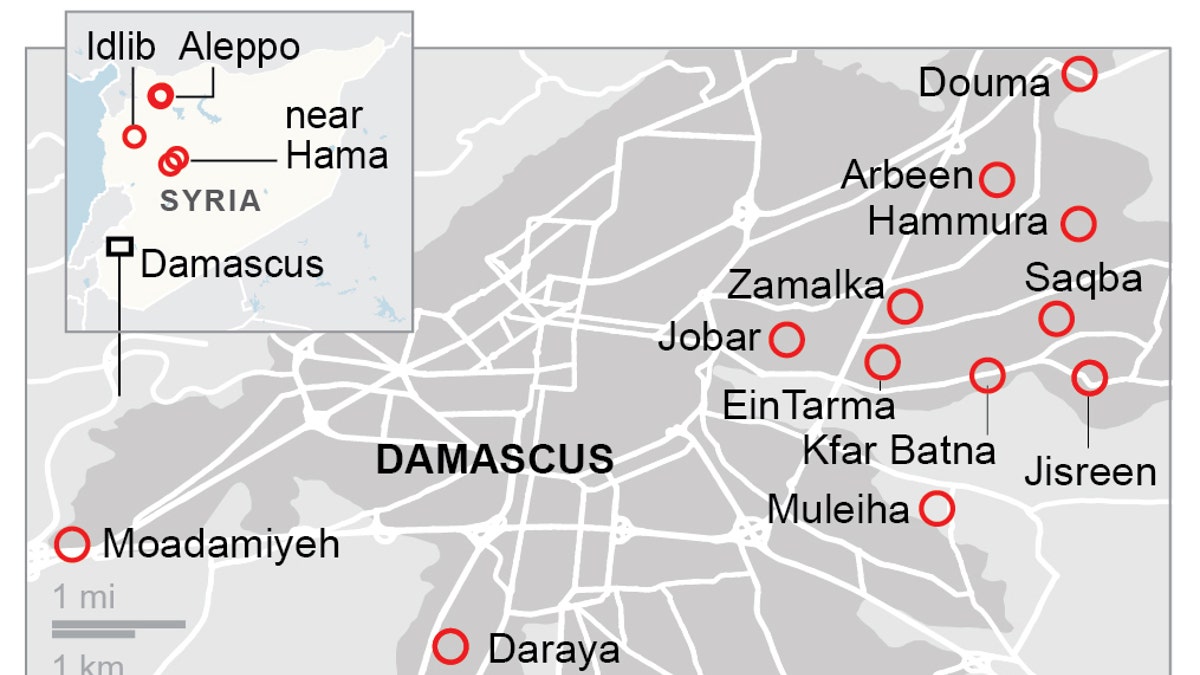

Chemical attacks in Syria since 2012 (The Associated Press)

“The whole world saw Omran and learned about him and his tragedy, which is not false. I am fully prepared to sit in front of Bashar Assad and call out his lies,” he said. “I was in there in Aleppo and we were bombarded by air raids. I was there with my lens and I have a full archive of footage.”

Other activists have also captured footage and photographs of the traumatized child in the ambulance that night, including the Aleppo Media Center as featured above.

The viral image of Omran ignited not only an immediate awareness of the dire situation in Syria, but was also a bump in donations for major NGOs operating in the area. Raslan said that the attention devoted to the video and photograph did not change his life and he did not get any prize for it, but it “helped the world to witness the crimes of the government.”

“I think photography sometimes stops Assad a little bit because of the intensity of the international pressure, after the world sees these massacres,” he noted.

LIFE IN WAR-TORN SYRIA: BOMB BLASTS AND NO UTILITIES, BUT COFFINS ARE FREE

SYRIA EVACUATION POSTPONED AFTER BLAST KILLS 80 KIDS

Raslan remembers that night vividly: The razed six-floor building that Omran’s family once called home, the bleeding bodies, the chaos and crying as survivors swarmed to medical staff for help. But, he emphasized, Omran’s condition was a “unique case" and after shooting some video, he stopped to take some stills.

“Omran was in the ambulance exhausted, very shocked at the fall of the rocket near him. When I capture many of the children, they are crying and screaming,” Raslan recalled. “But Omran was silent, which distinguished him from the rest of children that day.”

And it struck an extra chord close to home.

“When Omran was bombed, I thought of my child who was only four days old,” he continued. “I lived in Aleppo and I suffer what everyone suffers there. After that night, we were forced out of Aleppo and into a bigger disaster. I lost my home, my land, my neighborhood, my neighbors, my everything.”

But that night on the job is just one of many for Raslan to fold into memory as the 6-year civil war drags on, with little end in sight.

“I wished that the picture would have stopped the bombing,” he added. “But still, I want the world to know that there are thousands of Omrans suffering. I want the world to see all the children who are being bombed.”