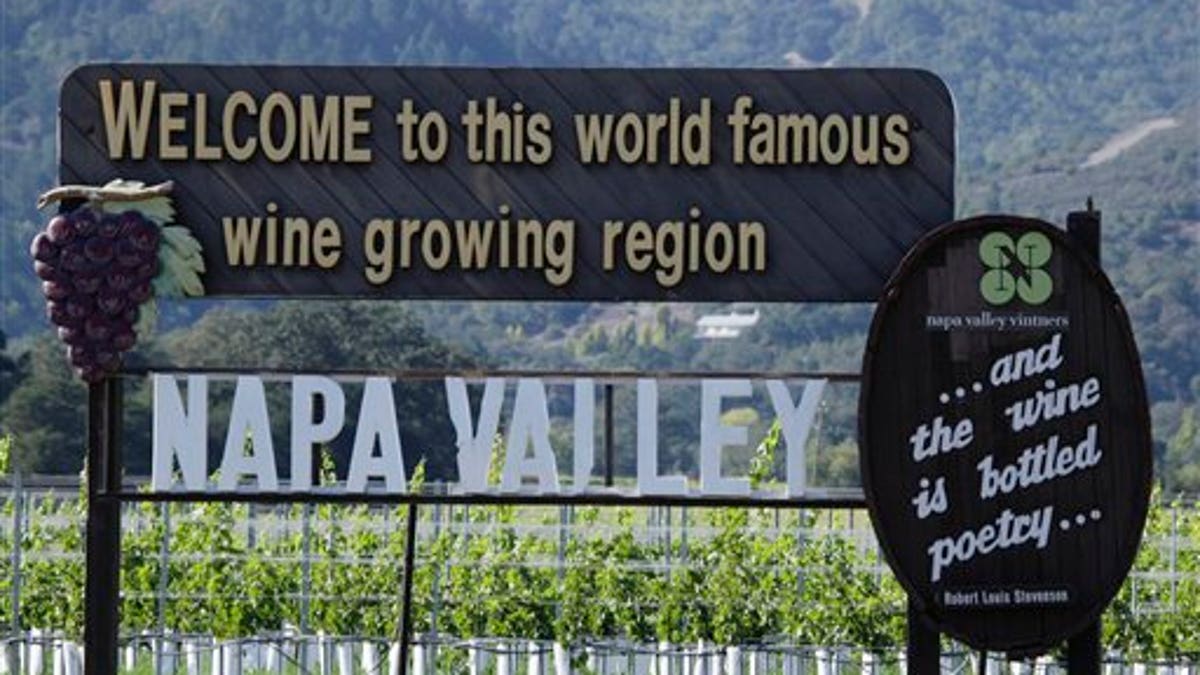

Oct. 27, 2011: A sign along Highway 29 welcomes visitors to the Napa Valley in Oakville, Calif. (AP)

NAPA, Calif. – Napa Valley wine producers will go a long way to protect their good name, all the way to Thailand if necessary.

That is the latest country that has awarded Geographic Indication status to Napa wine, which means they have agreed not to allow sales of wine labeled "Napa" if the grapes inside are not from that California region.

The agreement, reached late last year, is part of a campaign for truth-in-wine-labeling laws supported by a loose-knit cohort of wine regions around the world -- a movement that has gotten a boost from the general trend of consumers seeking ingredient integrity.

"What has been on our side is consumer awareness of, and appreciation for, the place where the product they're consuming comes from and paying more attention to labels, paying more attention to how things are produced," says Linda Reiff, executive director of the 420-member Napa Valley Vintners association.

For Napa Valley producers, the name campaign began during the late `90s on a defensive footing when producers lobbied for a 2000 state law requiring that any wine with "Napa" in its name consist of at least 75 percent Napa grapes.

That law was intended to stop Bronco Wine Co. from selling non-Napa wine in bottles labeled "Napa Creek" and "Napa Ridge," existing brand names that had been purchased by Bronco.

Bronco sued, but the law was upheld. The case ended in 2006 after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Bronco's final appeal. (Meanwhile, Bronco would go on to introduce the hugely successful "super value" wine known as Two Buck Chuck.)

The trade association continues to stay on the defensive, monitoring labels filed with the name "Napa" on them and taking steps where possible. A current concern is the new "Nava Valley" wine region in China.

But they have also moved into the proactive side, winning Geographical Indication status from the European Union and India and joining forces with a number of other global wine regions who have signed a declaration to protect regional wine names.

"We all realized that we were on the same page," says Sam Heitner, spokesman for the U.S. Champagne Bureau. "There is a common bond for quality wine-producing regions around the world. It is not a country-vs.-country issue; it is quality wine regions finding commonality."

Trade groups representing 15 appellations have signed up so far, including the Rioja region in Spain, producers in Portugal and the Wine Industry Association of Western Australia.

But agreement on the name campaign is not unanimous.

A major issue has been the use of the terms sherry, Champagne and port on U.S. brands. Those terms originated as styles of wine produced in Jerez, Spain; Champagne, France; and Porto in Portugal. In 2006, U.S. officials signed an agreement preventing new producers outside those regions from using the three designations, but existing brands were grandfathered in.

That is something that continues to irk European producers.

But the San Francisco-based Wine Institute, a trade association, denies that using terms such as "American Champagne" is misleading since producers are required to put on the label the geographic location of where the wine was produced. They also note that bottles labeled "California Champagne," have been legally produced and sold in the United States since 1857.

But Heitner points out that several U.S. producers, including the highly regarded Schramsberg winery in the Napa Valley, switched to putting the region-neutral "sparkling wine" on their labels without losing customers.

He sees the issue as underscoring the importance of "being upfront and proud of where one's wine comes from."

The point of protecting naming rights, says Reiff, is to give consumers confidence that "wherever they are in the world, when they purchase a bottle of wine that has Napa on the label, that it's truly Napa wine in the bottle."

Including, now, in Thailand.