Police officer suicide rate more than doubles line of duty deaths

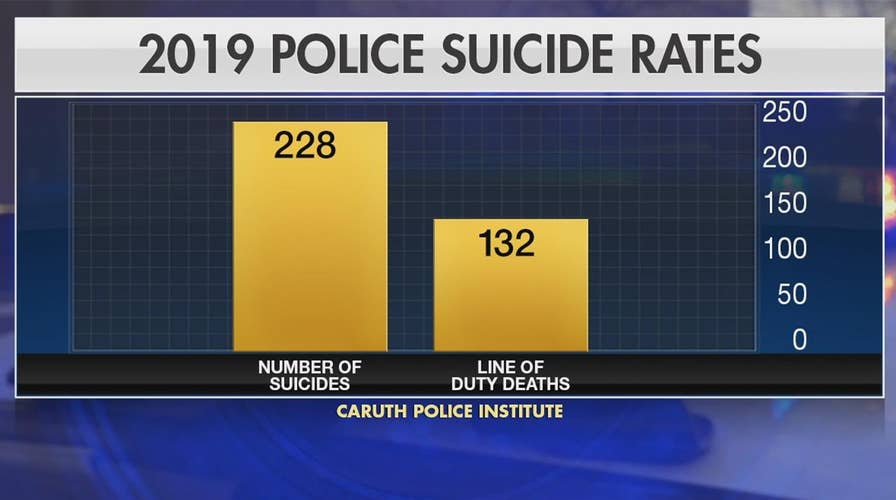

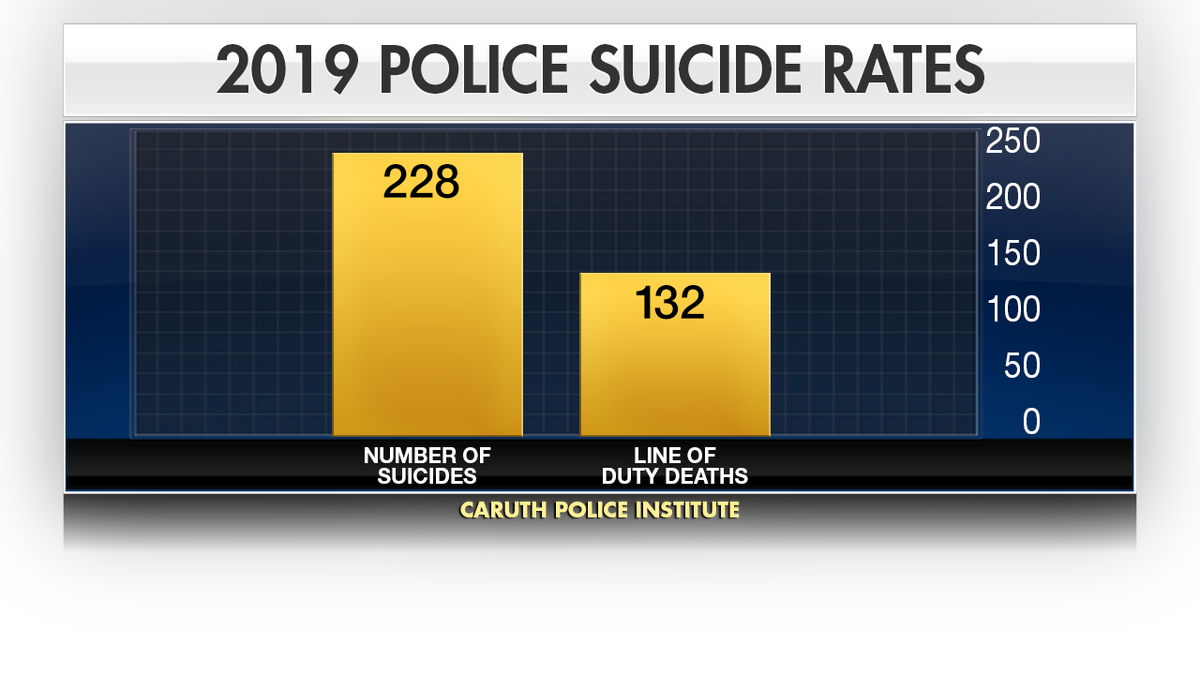

In 2019, 132 police officers died in the line of duty. That figure was more than doubled by the number of officers committing suicide.

AUSTIN, Texas -- The number of police officers who died by suicide in 2019 was more than double the number killed in the line of duty, according to a study -- and one organization is aiming to change the startling statistic with a broader peer networking program.

The Blue H.E.L.P. study showed 228 officers died by suicide, while 132 officers died in the line of duty in 2019. Texas ranked third with 19 suicides in 2019, behind New York with 23 and California with 21. The organization has aimed to call attention to mental-health concerns among law enforcement, with H.E.L.P. standing for “Honor. Educate. Lead. Prevent.”

“As a police officer, you never really leave your battlefield, you are constantly faced with the chronic stress of your work environment,” Caruth Police Institute Interim Executive Director BJ Wagner said.

According to Blue H.E.L.P. and the Caruth Police Institute, 228 officers died by suicide in 2019, more than double the number of officers killed in the line of duty.

Wagner said it’s because of the rise in police office suicides that the institute has been looking to put together the Texas First Responders Peer Networking Program, which ideally would eliminate officer suicides in the Lone Star State.

“It would be a statewide initiative saying that law enforcement suicide is no longer an acceptable statistic in Texas, we want to end it,” Wagner said.

The institute has been looking to get secure from the state in order to set up six hubs across the state that would provide a “battle buddy” to each officer struggling with mental, emotional or physical health.

As of now, programs like this have been offered only on a smaller scale, like at the Austin Police Department.

The Austin Police Department has a unit dedicated to helping the mental and emotional health of police officers. (Hunter Davis/Fox News)

“What we are trying to do is educate our peers,” Joe Brown with the Austin Police Department Peer Networking Unit said. “Our job is to foster relationships and build rapport so they feel comfortable to reach out to us.”

The Austin Peer Networking Unit has been active since 2006, helping any officer in or outside the department cope with the trauma of the job.

“I think as a profession, we have done a very bad job of reaching out for help and getting the help that we need in dealing with a career of trauma,” Brown said. “What we do is tell our officers, if they are in a time of need or see someone struggling, then they can reach out to us.”

The unit also taught a suicide-prevention class in 2019, educating the department on potential warning signs and some of the resources available to people in crisis and those who know someone in crisis.

“You work long hours and you deal with a variety of calls in one shift, and it’s something that officers have to deal with on an everyday basis, which is why we try to educate our peers and say, ‘Hey, you are going to experience some traumatic events and you’re going to have a biological reaction to that,’” Brown said.

The unit has boasted 100-percent success over the last 13 years, losing no officers to suicide. Its members said a program on a state level would only help them with their mission to save their brothers and sisters in blue. “We are a large entity and if you are looking at these smaller ones with eight people or 10 people, it is taught to have what we do, which is why I think it would be helpful in those areas,” Sgt. Tim Kresta said.

The program could assist people like Chris Jaramillo, a military veteran whose father, Officer Albert Mendoza-Jaramillo, died of suicide in 1992. He was an officer with the Austin Police Department for 10 years before he took his own life.

“He committed suicide on December 13, 1992. There is a lot of speculation as to why he did it, substance abuse and trauma from his job that he wasn’t dealing with,” his son said. “It was shock and the week prior to him committing suicide, he made me promise that if anything ever happened to him, I wouldn’t cry.”

Chris Jaramillo was a United States Marine and said he’s gone through his own battles with substance abuse after a battle buddy of his died in uniform.

“It was an incident in Afghanistan. We were on a dismounted patrol and we were sweeping for IEDs, and a good buddy of mine triggered an IED that caused a traumatic brain injury and killed him in the process,” Jaramillo said.

The Marine veteran was honored with a Purple Heart for his service and said, because of his own trauma, he’s now able to understand what his father may have been going through 28 years ago.

“Veterans experience similar traumas to police officers, witnessing scenes that aren’t pleasant. As a veteran, I didn’t want to ask for help because it wasn’t the thing to do, because you got the stigma of being labeled with a mental illness and just like police officers, it wasn’t something you bring up,” Jaramillo said. “You drink, you go hang out with your buddies and that is how you deal with it.”

The veteran said, although he felt similar to what he believed his dad felt, he chose to get help.

“It is heartbreaking because I was in that same place where he was. And, just because he did it and I witnessed it and experienced it, but the fact that I asked for help and things got better was heartbreaking, because it could have helped him too,” Jaramillo recalled.

He said it’s because of this understanding that he believed a program like the Texas First Responders Peer Networking Program would be helpful.

“A peer is going to be around you more than a doctor or whatever, and they are going to see those hidden secrets. And, those secrets need to be brought to light by having a peer say, ‘Hey, you need help,’ or, ‘Hey, I got a buddy that needs help,’ and take that to the peer network to get the officer the help they need,” Jaramillo said. “It’s a big thing to have a good support system so that way, you know it would have helped him out because he would have been able to get to that doctor that may have changed his mind.”

MISSISSIPPI MOM WORRIED FOR SON'S SAFETY AFTER DEADLY PRISON RIOTS

Jaramillo added that any officer or anyone else struggling with mental or emotional health should know that someone else was looking out.

“The strongest thing someone can do is ask for help and say, ‘Hey, I cannot do this on my own. It hurts [losing someone] so asking for help, I’ll keep your loved ones from experiencing the pain,” Jaramillo said.

The Caruth Police Institute has aimed to have the program partially operational by December and then fully operational by the summer of 2021, but it’s all dependent on funding.

The Caruth Police Institute is aiming to place six peer networking hubs across the Lone Star State. (Fox News)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“Across the last two legislative sessions, Texas has really been a model across the country on how to create state and local partnerships to provide mental help services across the region, across the state, and allowing committees to design what works well by providing match dollars with the state,” Wagner said. “We are looking toward some of those opportunities to fund the Texas First Responders Peer Network, but we are also looking at other grants and philanthropic opportunities to help launch this network.”

The Caruth Police Institute, a partnership between Dallas police and the University of North Texas at Dallas, is hoping to place 6 different hubs across Texas: in Irving, Austin, El Paso, Lubbock, Tyler and Rockport.