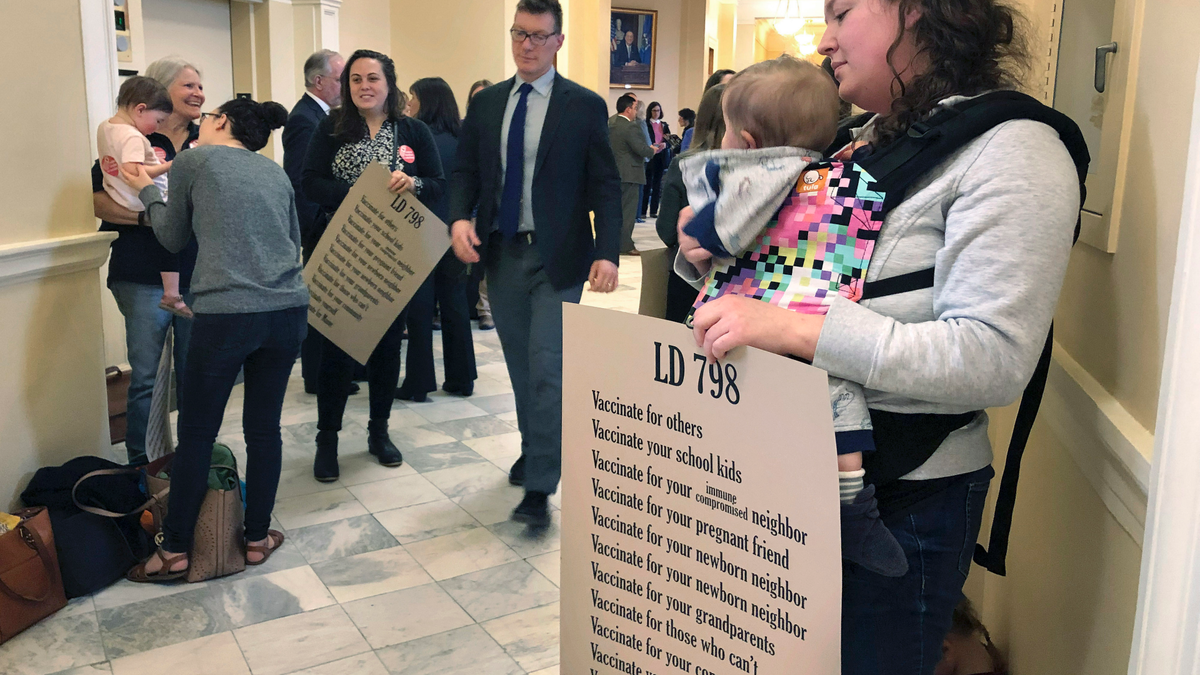

Kate Herrold, of Falmouth, holds her daughter with other mothers in a hallway, Thursday, May 2, 2019, at the Statehouse in Augusta, Maine, where the Senate passed a bill ending non-medical vaccine exemptions. The bill would end religious and philosophical opt-outs by 2021 for public school students, as well as employees at nursery schools and health care facilities. It faces further legislative action in both chambers. (AP Photo/Marina Villeneuve)

Connecticut's Attorney General gave state lawmakers the legal go-ahead Monday to pursue legislation that would prevent parents from exempting their children from vaccinations for religious reasons, a move that several states are considering amid a significant measles outbreak.

The non-binding ruling from William Tong, a Democrat, was released the same day public health officials in neighboring New York called on state legislators there to pass similar legislation . Most of the cases in the current outbreak have been in New York state.

Tong offered no stance on whether the Connecticut General Assembly should scrap the exclusion, but he made it clear in the seven-page letter there is nothing in the law that would prevent the state from ending the exemption.

"There is no serious or reasonable dispute as to the State's broad authority to require and regulate immunizations for children: the law is clear that the State of Connecticut may create, eliminate or suspend the religious exemption," Tong wrote, adding that it's within the state's "well-settled power to protect public safety and health."

Connecticut is just one of several states considering whether to end longstanding laws that allow people to opt out of vaccinations for religious purposes. In the face of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, some have alleged religious exemptions have been abused by "anti-vaxxers" who believe vaccines are harmful despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

But the proposals to eliminate the opt-outs have also sparked emotional debates about religious freedom and the rights of parents.

Most religions have no prohibitions against vaccinations, according to Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Tennessee. Yet the number of people seeking the religious exemption in Connecticut has been consistently climbing. There were 316 issued during the 2003-04 school year, compared to 1,255 in the 2017-18 school year.

Democratic House Majority Leader Matt Ritter, of Hartford, who wants the General Assembly to vote on ending the exemption, had requested Tong's formal opinion — his first since taking office in January.

It's unclear when or if Connecticut lawmakers might vote on ending the exemption this session, which ends June 5.

"I think there's a growing consensus that Connecticut is going to need to do something pretty bold in the coming weeks, coming months," Ritter said last week.

While Connecticut's statewide immunization rate is high — 96.5% of kindergarten students are vaccinated for measles, mumps and rubella — concern persists about the growing number of families that have sought the religious exemption in recent years and the likelihood of bogus exemptions.

The state's Department of Public Health released school-by-school data for the first time on Friday that showed more than 100 out of more than 1,300 public and private schools listed fell below the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's recommended 95% immunization rate among kindergarteners.

In neighboring New York, medical organizations and county health officials on Monday called for eliminating that state's religious exemptions for vaccines and allowing only medical exemptions. Most of the nation's 764 reported cases of measles, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have been in New York. Health officials there say the majority of its cases have occurred in Orthodox Jewish communities in New York City and nearby Rockland County.

Connecticut has had three confirmed cases of measles, including one tied to New York.

Last week, the Maine state Senate moved to end philosophical exemptions to vaccines but stopped short of ending religious exemptions. The bill still awaits further legislative action. And last month, California's Senate Health Committee approved a proposal to give state public health officials, instead of doctors, the power to decide which children can skip their shots before attending school.

Meanwhile, the Colorado legislature last week abandoned efforts to make it harder for parents to option their children out of vaccines. The bill had drawn big crowds of vaccination opponents to the state Capitol.

In Connecticut, parents' rights groups, socially conservative groups and dozens of Republican lawmakers have balked at the discussion of rolling back the stateeligious exemption. Angry parents have appeared at the Capitol for weeks, making it clear to legislators they believe their rights are at risk.

"They want to stop people who they think are abusing the religious exemption and that is incorrect. The government has zero right to ask you what your religion is or for you to explain it," said Shannon Gamache, of Ashford, in a recent interview. She chose not to have her son fully vaccinated after he experienced what she believes were adverse side effects from a vaccine.

All 50 states have laws requiring students to have certain vaccinations. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, all but Mississippi, West Virginia and California grant religious exemptions. As of Jan. 30, the conference said 17 states allowed people to exempt their children for personal, moral or other philosophical beliefs.