Fox News Flash top headlines for February 18

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

A peaceful march in protest of racial injustice set out from Selma, Ala., on March 7, 1965, but was met with violent resistance from local law enforcement in an event that became known as "Bloody Sunday."

Civil rights demonstrators planned to march to the state capital in Montgomery to bring attention to the legal barriers set up to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote and to police violence following the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 26-year-old church deacon, in Marion.

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT: WHAT TO KNOW

Alabama's segregationist Gov. George Wallace opposed the march and ordered state troopers to put a stop to it. Law enforcement deployed tear gas and used clubs and to attack the marchers.

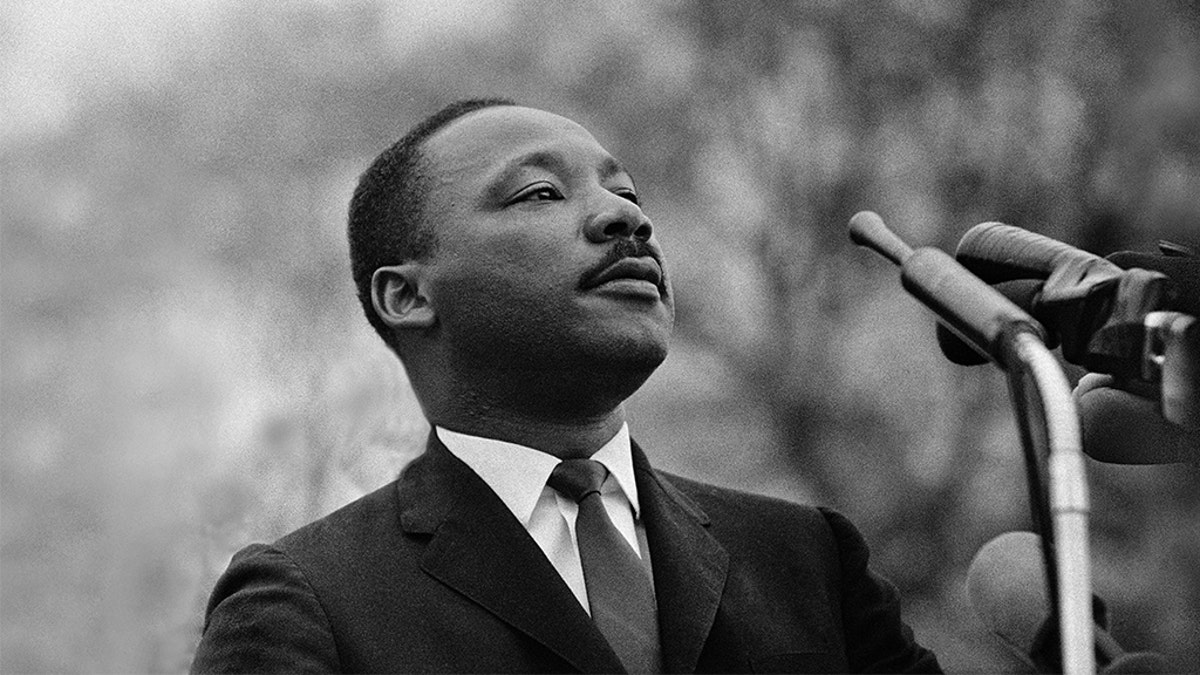

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking before a crowd of 25,000 civil rights marchers in front of the state capital building on March 25, 1965, in Montgomery, Ala. (Stephen F. Somerstein/Getty Images)

The events of "Bloody Sunday" were captured on television cameras, shocking and outraging the American public. Over the next two days, demonstrations in support of the marchers were held in dozens of cities across the country.

Just over a week later, President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced legislation into Congress that would become the 1965 Voting Rights Act and called the events in Selma a turning point in the civil rights movement.

John Lewis helped lead the Selma march

Before his days serving in the U.S. Congress, John Lewis was the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

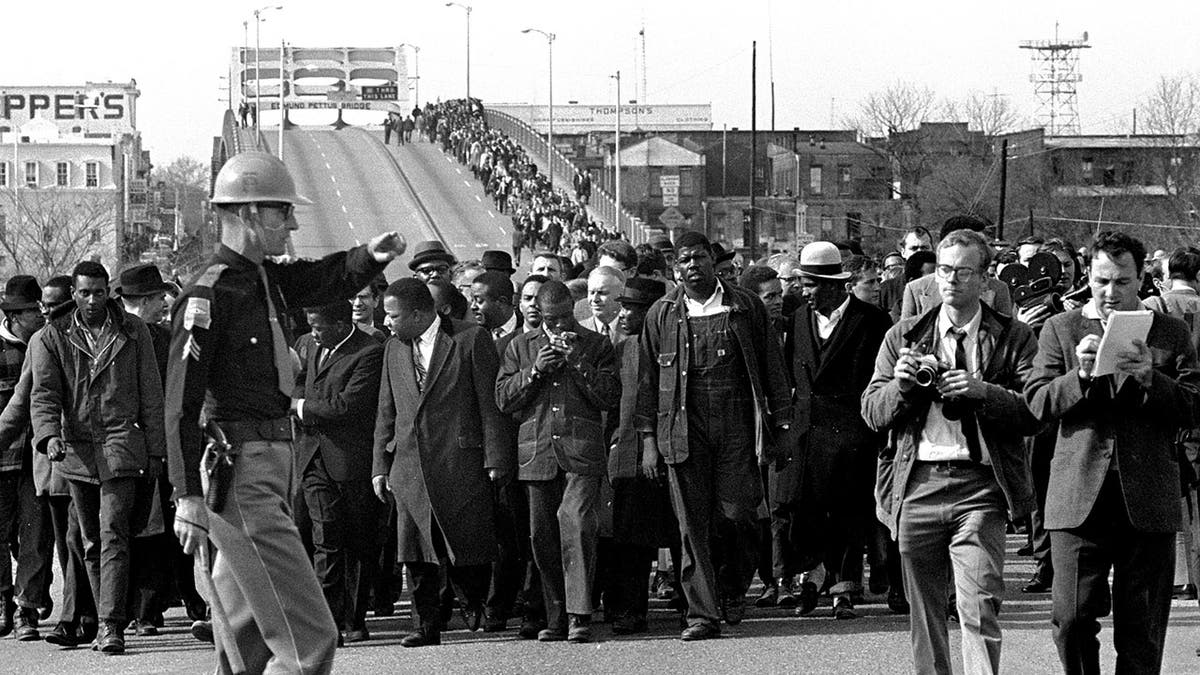

In this March 10, 1965, file photo, demonstrators, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stream over an Alabama River bridge at the city limits of Selma, Ala., during a voter rights march. King's participation in the 54-mile march from Selma, Ala., to the state capital of Montgomery elevated awareness about the troubles blacks faced in registering to vote. (AP Photo/File)

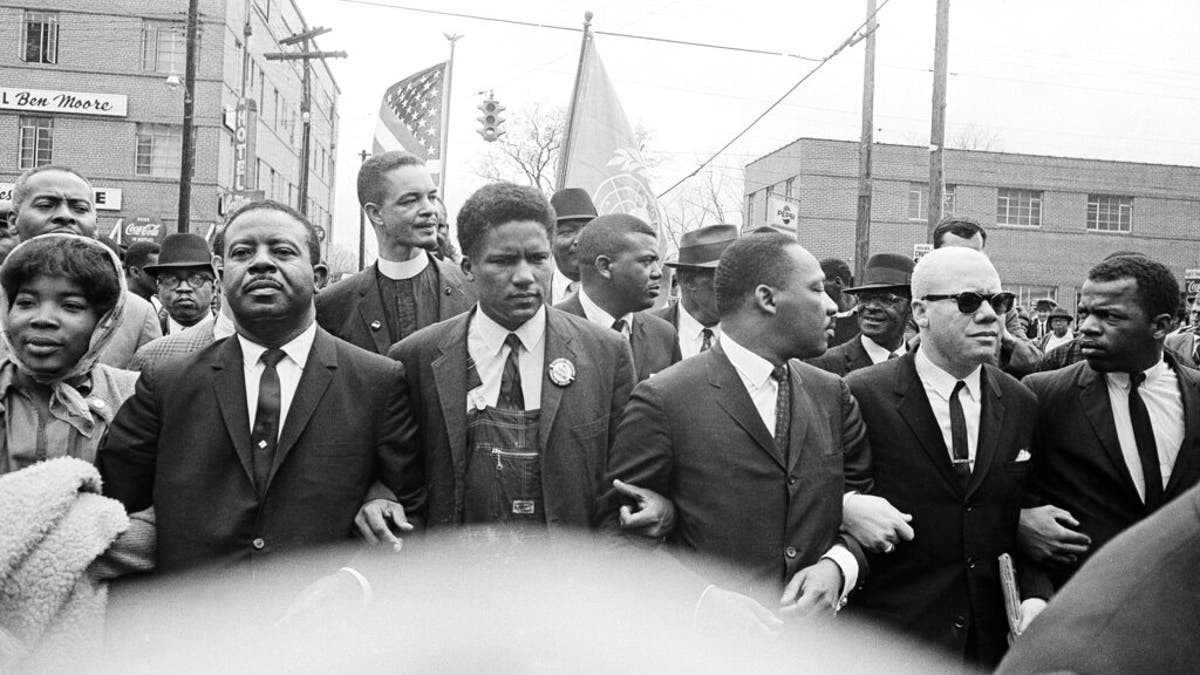

He and Martin Luther King Jr.'s colleague, Hosea Williams, helped lead the peaceful march from Selma on "Bloody Sunday" while King was set to join them later in the day.

However, when Lewis, Williams and some 600 demonstrators arrived at the Edmund Pettus Bridge that stretched across the Alabama River and out of Selma, they faced a force of lawmen that included sheriff's deputies, dozens of state troopers and a deputized posse.

In this March 7, 1965, file photo, a state trooper swings a billy club at John Lewis, right foreground, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to break up a civil rights voting march in Selma, Ala. Lewis sustained a fractured skull. (AP Photo/File)

The lawmen refused to speak with the demonstrators and ordered them to disperse before violently beating and chasing the marchers.

Lewis was struck in the head and hospitalized along with dozens of other marchers.

America sees 'Bloody Sunday' on TV

The brutal assault was broadcast to the homes of millions of Americans who were watching ABC's telecast of "Judgment at Nuremburg" (1961), a film about the prosecution of Nazi war criminals.

ROSA PARKS: WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT THE 'MOTHER OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT'

News anchor Frank Reynolds interrupted the film to show the footage from the march.

The footage outraged Americans and broadened support for the marchers' cause.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act, regarded as one of the most extensive pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history, helped overcome the legal barriers imposed at the state and local levels that prevented Black Americans from exercising their right to vote.

In this March 17, 1965, file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., fourth from left, foreground, locks arms with his aides as he leads a march of several thousand to the courthouse in Montgomery, Ala. From left are: an unidentified woman, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, James Foreman, King, Jesse Douglas Sr. and John Lewis. (AP Photo/File)

President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced the legislation into Congress on March 15, 1965.

The legislation would suspend literacy tests required for African Americans to determine voter eligibility and challenged the use of poll taxes when signed into law on Aug. 6.

The Road to Montgomery

On March 21, King led thousands of marchers out of Selma to Montgomery after a judge ruled that Wallace could not legally stop the demonstrators.

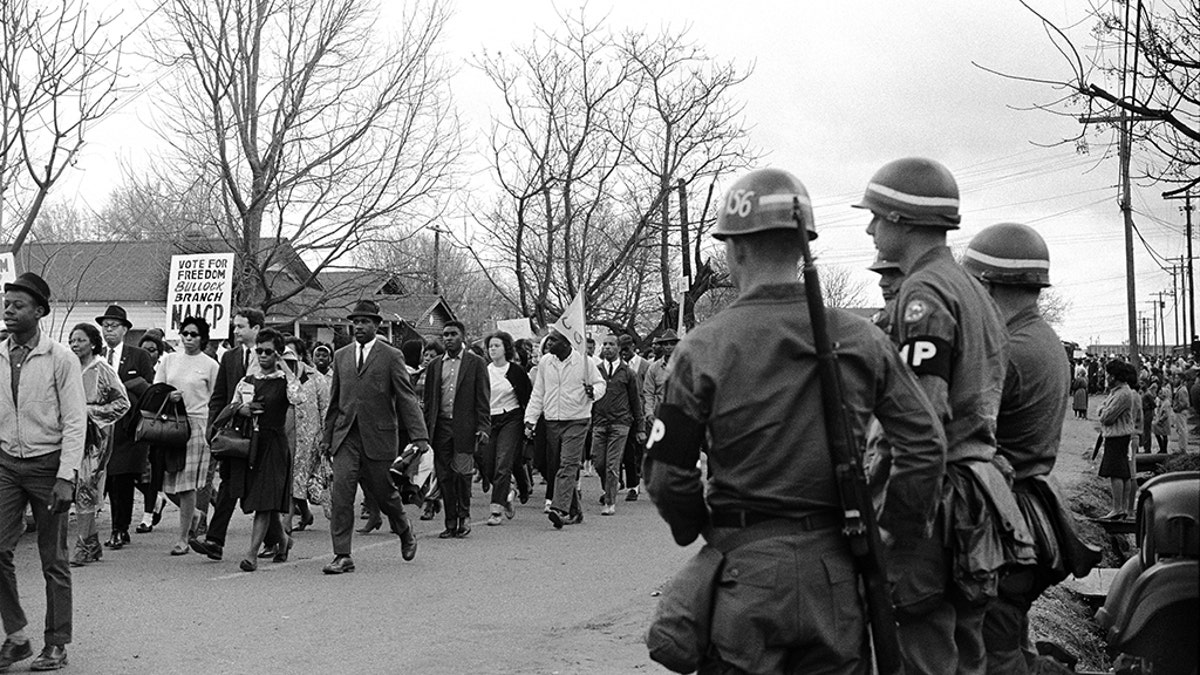

Federal Army troops guard civil rights marchers along route 80, the Jefferson Davis Highway, during the Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights March on March 25, 1965, in Montgomery, Ala. (Getty)

Swelling to numbers over 25,000, the marchers were protected by thousands of Alabama National Guardsmen, U.S. Army soldiers, federal marshals and FBI agents under the order of Johnson.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Arriving at the capital five days later, King delivered his famous "How Long, Not Long" speech.