Former KGB spy on Russian espionage as Putin's invasion of Ukraine continues

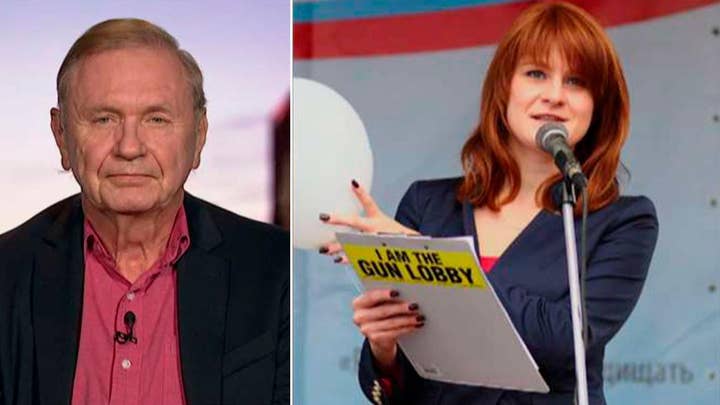

Jack Barsky, a former KGB agent, joined 'Fox & Friends Weekend' to discuss modern-day espionage and his experience as a former spy.

Jack Barsky joined a pre-arranged Friday morning Zoom meeting 18 minutes before it was scheduled to begin.

Wearing a navy blue, long-sleeved sweater with a white, collared shirt underneath, he appeared the everyday gentleman – an all-American father, possibly a grandfather – as he sat with his arms folded in front of a pre-set background of the Hudson River as the interview began.

"So, literally what's going on in the world right now with Ukraine? That's exactly what [illegal spies] were created for."

Barsky, now a 74-year-old author and public speaker, lives a life that appears to be that of a typical American citizen. But his life and his story are anything but typical.

RUSSIA INVADES UKRAINE: LIVE UPDATES

Barsky was born Albrecht Dittrich before he was recruited by the now-defunct KGB, which later became the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (FSB). He was trained and groomed for years before he spent a decade living a double life as a Russian spy in New York City.

"I wound up to be one of the best-trained agents they ever sent to the United States," he told Fox News Digital.

ALBRECHT DITTRICH

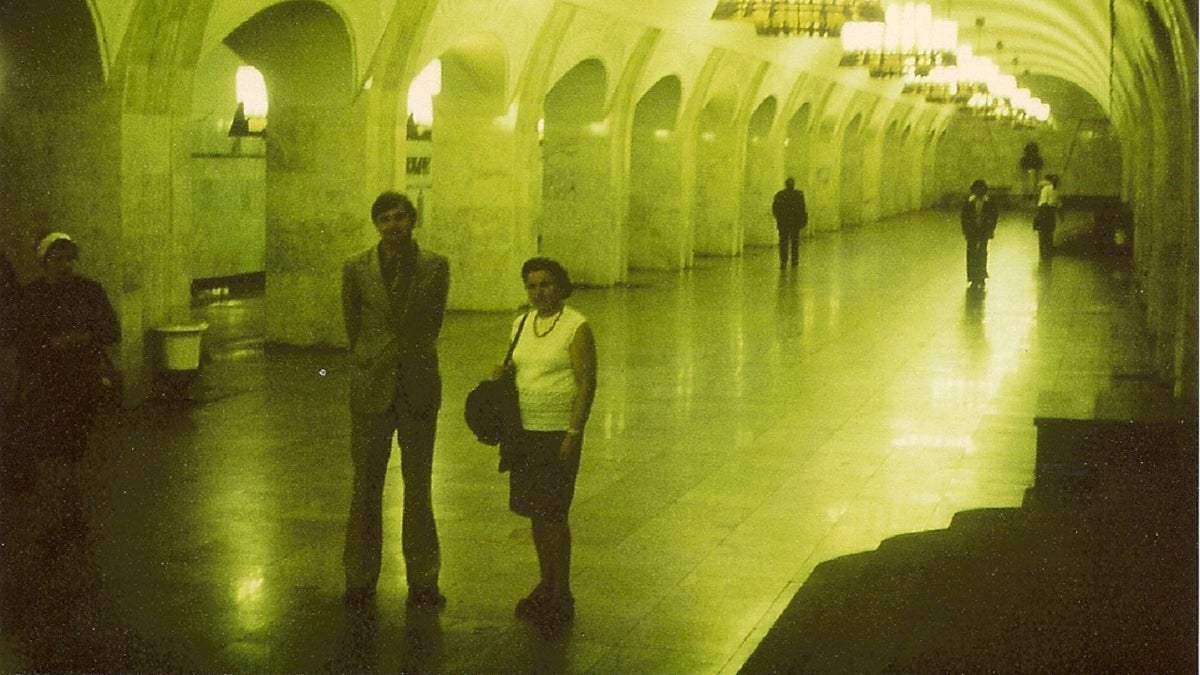

This undated photo shows Jack Barsky with his mother when she visited him in Moscow while he was training to become a KGB agent. (Courtesy of Jack Barsky)

Albrecht Dittrich was born in Germany in 1949. He was raised in a part of the country that became the German Democratic Republic – known as "East Germany" – a vassal state dominated by the Soviet Union.

"I grew up as a good little communist," Barsky told Fox News Digital.

"From my right side, this short fellow in a black trench coat, he comes really close. And then he whispers in my ear: 'You gotta come home or else you're dead.'"

Given the Stasi’s – the secret police’s – practice of keeping records on all of East Germany’s residents, Dittrich’s good grades and allegiance to the communist party caught the attention of the KGB not long after he entered the workforce. He spent a year and a half communicating informally with recruiters before he flew to the KGB and Soviet Army headquarters in Berlin and met with the head of the security agency.

"Out of the blue, he asked me: ‘So what? Can we count on you?’" he recalled of his meeting with the top-ranked KGB official.

A Russian KGB/Stasi helmet in front of Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, just two days ahead of the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Nov. 7, 2019, in Berlin, Germany. (Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Dittrich was given until noontime the next day to provide a final answer.

"I thought it through, I said, it is an opportunity to help the world revolution, to free some of the suppressed folks in the Western countries to have the good life," he said with a chuckle. "I said yes. I had no idea what I really signed up for."

Five years later, he said, "I showed up in the United States."

BECOMING JACK BARSKY

The gravesite for Jack Barsky, the 10-year-old boy who died in Maryland and whose identity Albrecht Dittrich ultimately assumed. (Courtesy of Jack Barsky)

Dittrich underwent two years of basic training before he was sent to Moscow for another two and a half years. There, the emphasis was not only on honing in on his spycraft skills, but being able to speak English so well that only a glint of an accent was evident.

When his handlers determined he was ready, Dittrich said goodbye to his mother, his wife and their young child, and left behind his life in Germany. From there, he took "a long zigzag trip through Europe with multiple forged passports" – and varied which documents he used to prevent traceability. He entered the U.S. in Chicago and made his way to New York City, ditching the bogus passports along the way.

"In the fall of 1978, I showed up in the United States," he said. "The only documentation I had was a certified copy of a birth certificate in the name of Jack Barsky."

Dittrich took on the identity of Jack Philip Barsky, a 10-year-old boy who died in Maryland in September 1955.

The mother of the original Jack Barsky bore the maiden name Schwartz, which Dittrich’s handlers preferred because of the surname’s presumed German or Jewish-German roots, Barsky said. He used it as a way to explain away any remnants of a German accent, and told anyone who questioned him he was born into a bilingual household in Orange, New Jersey.

From then on, Albrecht Dittrich was someone from a past life – a life that was revisited only once every two years, when Barsky was granted a trip back home.

But despite the fact that the actual Jack Barsky was not around to interfere, becoming the new Barsky "wasn’t easy."

"I tried once to get one birth certificate and that failed, because the office that issued the birth certificates also cross-referenced death certificates, and I wound up asking for the copy of my birth certificate after I died," he recalled. His second attempt was successful, but he wasn’t yet out of the woods.

One Madison Avenue, Manhattan, New York (Google Maps)

He then covered himself in dirt and played the character of a farmworker, because the farm industry was exempt from Social Security requirements at the time, when he went to the Social Security office to get the necessary documentation.

"I made myself into somebody who had just jumped off the potato truck. I rubbed soap into my eyes to make them red, I had stubble on my face, the hair wasn’t really combed well, dirty T-shirt," he said. "Two weeks later, I got the Social Security card in the mail, and I was allowed to actually legally work in the United States."

Barsky moved to New York City’s Upper East Side, but avoided almost any social interaction for about a year, until he had all his necessary documentation. His first job was working as a bike messenger, which he did for two and a half years. When he was on the road or interacting with customers – and even when he had downtime in the office – he absorbed everything.

Barsky then went to college, and graduated from Baruch College as Class of 1984 valedictorian.

By that point, he "felt rather comfortable in my American skin," Barsky said. He took a job as a computer programmer for MetLife, working in the One Madison Avenue high-rise – all the while still secretly working for the KGB and feeding his handlers any and all information.

"That's when I finally was on my way to become middle class, in the end, the upper middle-class person, at which point I would have become a much more dangerous agent," he said. "But before that happened, I quit."

‘MISSION ACCOMPLISHED’

Jack Barsky (right) with his mother, center, and his KBG handler, named Sergej (Courtesy of Jack Barsky)

"The first and foremost aspect of the mission of folks like us was just there, being in the U.S., being available," Barsky said. "We were supposed to be on standby just in case," he added, referring to the possibility that diplomats in the U.S., most of whom were KGB spies, were kicked out of the country.

He added that he was sent to the U.S. with the goal of "collecting information about foreign policy, getting close to foreign policy decision makers or influencers."

His handlers gave him names of people and organizations with whom they wanted him to get cozy, including the Hudson Institute, "a conservative think tank," and Zbigniew Brzezinski, former national security adviser under President Carter.

"That was a pipe dream," he said. "I never got to a point where I was positioned in society to have a realistic explanation why I would want to befriend some of these people."

He also wrote periodic reports about how the American public was responding to world events and tried to make as many other connections as possible.

"The other thing that was important to them was for me to get to know as many people as possible – contacts, contacts, contacts, that’s what I heard a lot. And then profile them, analyze them, send profiles to Moscow for them to determine whether they would be good candidates for recruitment."

This undated photo shows Jack Barsky and his colleagues at MetLife. (Courtesy of Jack Barsky)

He said he was never told what happened with any of the people he reported, or if and how KGB higher-ups used the information he shared.

Barsky also spoke regularly to his handlers in Moscow, and communicated with them at least weekly via radio transmissions. In New York, he and his network communicated via signals in agreed-upon spots – a detail that becomes important later in Barsky’s story – and passed information using "dead drops," a process that entails leaving items or documents in an agreed-upon spot for someone else to retrieve later. He was allowed to mail two letters with "secret writings" to his loved ones per month, he said.

Asked if he recalled any moment where he thought, "mission accomplished," Barsky told Fox News Digital even developments that might seem small – getting his Social Security card, safely returning to Moscow and East Germany every two years – were seen as big steps.

Getting his job at MetLife, and even his gig as a bike messenger, were seen as accomplishments.

"I had achieved probably the impossible, because there were so many situations where it was at best, 50-50 for me to actually get through and not fail," he said. "But again, this was a suicidal mission, quite frankly. And the fact that I actually established myself as an American, that was my, I believe, my biggest achievement."

THE RED DOT

This undated photo shows Jack Barsky and his infant daughter, Chelsea. (Courtesy of Jack Barsky)

Barsky realized he had to make a life-altering decision in December 1988, when the KGB began sending messages urging him to "get out." By that point, he was married, in his mid-30s, and living in Queens with an 18-month-old daughter at home.

"There was a spot that we had arranged where agents could put some graphic signals. Very basic ... But the one that I remember the most is the red dot," he said. "The spot was at a supporting pole for the elevated A-train, so as I walked up the stairs and I would look at that particular spot. There was never anything there that was just routine."

But that changed early one Monday morning as he was on his way to work. For the first time ever, he spotted a signal: a red dot.

"That red dot meant I was in danger," he explained. "It was like, ‘Emergency!’ And I did nothing. I got on a train and went to work and stared at the computer screen for all day without doing anything."

The next message came during his regularly scheduled Thursday radio transmission.

"You got to get out. This is an emergency," the encrypted message stated, Barsky said. "We have reason to believe that you're being investigated by the FBI."

But he doubted what he was being told. Having years of experience looking over his shoulder and taking countermeasures to assure he was not being followed, he wasn’t convinced.

A commuter walks on the platform of the Woodside LIRR train station in the Queens borough of New York on Monday, Aug. 3, 2020. (Michael Nagle/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

He chose not to respond to the radio transmission, despite Moscow’s request that he confirm that he received the message and understood his instructions. They repeated the radio transmission every day, he remembered.

But "the most dramatic moment in [his] entire life" came roughly three weeks later, as he stood on the platform of a Queens subway station, still dark outside, around 6:30 a.m. or 7 a.m.

"From my right side, this short fellow in a black trench coat, he comes really close. And then he whispers in my ear: 'You gotta come home or else you're dead.'"

He said he had a choice: to take this as a serious threat against his life, or attribute the message to "a lack of understanding of the English language" or an exaggeration.

He had made his decision: He would leave behind his life as a spy and would stay with his wife and his budding American family.

Barsky did what he could to ensure that his family in Germany was safe, and sent them one final secret writing, in which he told them that the FBI might be after him. He told them: "I’m not coming home because I have HIV AIDS and that I may have a chance for treatment."

He asked friends within the organization in Moscow to send his family the money he had earned through his work. They did so and ultimately told them that Dittrich had died from AIDS.

His mother died in 1984, before she was able to learn the truth about her son.

‘JACK BARSKYS’ OF TODAY

Barsky’s story is no secret anymore. Though it took time and years of investigation, the FBI ultimately caught up to him, according to Barsky’s own details and interviews conducted in "The Agent," a podcast about his life.

To put the story simply, agents ultimately overheard via wiretap Barsky admitting to his wife that he had previously worked as a KGB spy. They arrested him and confirmed that he was telling the truth and was no longer working for the KGB. They then began working with him to better understand Russia’s secrets.

The Jack Barskys of today – spies sent from the Soviet Union, Russia or other similarly situated nations – are few and far between, but "they’re still around," former FBI special agent Robin Dreeke told Fox News Digital.

He estimated that there was only "a handful" of agents in the U.S. at one time.

"Jack is a great example of why there's not hundreds of them. Because they don't fulfill a huge function, and they take up a huge amount of resources and money," he continued. "Basically, you're paying an employee and a lot of time and resources and money to do not a whole lot … their main role and function is to perform when an event happens that they need to activate them."

And today’s spies rarely have the level of training that he received.

Dreeke, former head of the bureau’s Counterintelligence Behavioral Analysis Program, worked personally with Russian "illegals" – spies in the U.S. illegally and outside of diplomatic cover – during his time with the FBI New York’s Russian Military Intelligence Squad from 1997 to 2005. Dreeke's unit tried to recruit Russian spies and then neutralize them to protect American interests, national security and NATO allies.

Barsky’s training was "significantly higher" than what the general illegal spy will get, Dreeke told Fox News Digital.

"Jack did a lot of one-on-one training, as a matter of fact, all of his training was one on one, very in-depth. And typically, they go through schools... people in large classrooms," he said.

In addition to his "in-depth," "thorough" training, Barsky’s level of communication with Moscow was "much higher than normal," Dreeke said. His tasks, while not significantly different from those of the other spies, were "unusual" in comparison.

"The tasks he was given were really high tempo, operational-type stuff that generally, the actual intelligence officers (Russian diplomats in the country legally) will get, like him conducting those dead drops … that's pretty unusual for someone that's not legal," said Dreeke, who has since authored several books and founded a company, People Formula.

Illegal spies, Dreeke explained, are typically placed inside the country "for times just like this."

"Russians put illegals inside our country during the Cold War in case whoever went to war, and all the diplomats were expelled, Russia could still collect intelligence and run their operatives inside the country because they have a network of illegals," he said.

He added: "So, literally what's going on in the world right now with Ukraine? That's exactly what illegals were created for: They were created to not just do penetrations of government institutions and organizations, but also to be in place in case the diplomatic corps gets expelled."

RUSSIAN GOALS

The Kremlin towers in front of the Russian Foreign Ministry headquarters on March 18, 2021 (Photo by DIMITAR DILKOFF/AFP via Getty Images)

Today, with the spotlight on Russia amid the ongoing invasion in Ukraine, spies still lurking in the United States are likely operating on "high alert," Barsky said. Not only would they be more aware of what is happening in the country, but they would also be careful not to "become too aggressive" or potentially make mistakes.

"One of the tasks I had, and I was told that everybody who was operating in a foreign country was supposed to … look for any signs of the country preparing for war," Barsky explained. "Guaranteed … the Russian agents in this country are on high alert … To the extent you could do more to look for signs of preparation for war, you would."

He added that this would be the time that he would be reaching out to contacts he had made over the years, either those who were in the military or in companies that produced weapons.

Dreeke noted that spies who are living undercover in the U.S. would be reporting back about what people are saying, compared to, and in addition to, what the news reports are saying, but will be looking over their shoulders along the way.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"I suspect they will not be opening new sources of information, but only going to well-established human intelligence sources of information," Dreeke continued. "They are needing that information critically for policymaking – policymakers and decision makers on Russia's side. At the same time, though, they are now entirely paranoid about factions on their own side."