Revived legislation seeks to end monopoly of meat industry, open markets to small farmers amid coronavirus pandemic

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

As the United States meat industry has been struck from all sides amid the coronavirus pandemic, a long-languishing bipartisan bill is gaining momentum as a possible solution to keeping small farmers afloat, feeding families, and halting the wasteful slaughter of countless numbers of cattle.

"What this legislation would do is expand the exemptions and make it easier (for small farmers) to sell to places like grocery stores and restaurants," Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY) – who first introduced the legislation along with Chellie Pingree (D-ME) almost five years ago – told Fox News. "The same regulations that apply to multinational beef hackers that slaughter 10,000 animals a day shouldn't apply to a rancher slaughtering 20."

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}It's known as the PRIME Act, an acronym which means Processing Revival and Intrastate Meat Exemption, and is intended to "amend the Federal Meat Inspection Act to exempt from inspection the slaughter of animals and the preparation of carcasses conducted at a custom slaughter facility, and for other purposes." It ultimately seeks to "give individual states freedom to permit intrastate distribution of custom-slaughtered meat such as beef, pork, or lamb to consumers, restaurants, hotels, boarding houses, and grocery stores."

WHY FARMERS DUMP FOOD AND CROPS WHILE GROCERY STORES RUN DRY AND AMERICANS STRUGGLE

The act was re-introduced in the House last May, and Kentucky Republican Rand Paul and Maine independent Angus King have put forward accompanying legislation in the Senate. Massie said he now has 40 sponsors in the House and five in the Senate – both Democrats and Republicans – with 15 new representatives signing on in the last week alone as a result of the ongoing public health crisis that has crippled much of the farming community in recent weeks.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}From the purview of Massie, a rancher himself who owns 50 head of cattle in northeast Kentucky, "federal inspection requirements make it difficult to purchase food from trusted, local farmers, making it imperative for markets to open and to give producers the freedom to succeed and consumers the freedom to choose."

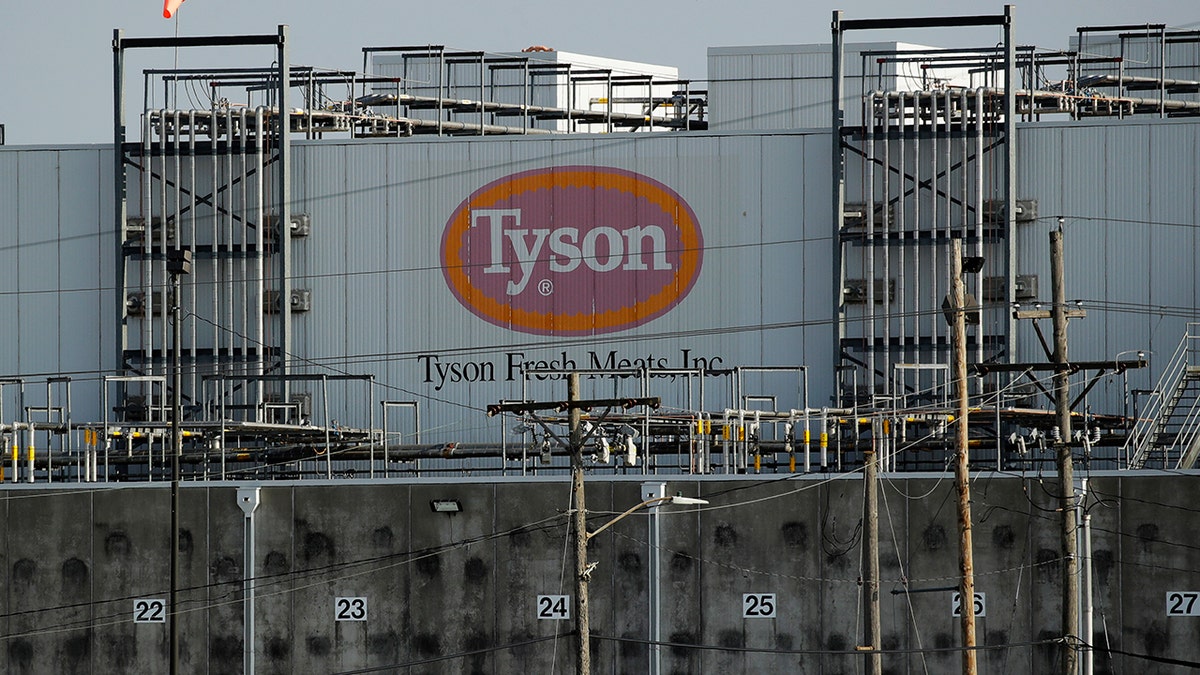

A Tyson Fresh Meats plant is seen Monday, April 27, 2020, in Emporia, Kan. President Donald Trump plans to order meat processing plants to stay open amid concerns over growing coronavirus cases and the impact on the nation's food supply. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Advocates of the legislation – which include the ever-evolving "farm-to-table" movement among urban gastronomists – contend it will help small producers compete in a market dominated mainly by meat processing conglomerates, all of which have been hard hit by the global pandemic.

In April, the biggest meat companies not only in the U.S. but the world – including Cargill Inc., Tyson Foods, JBS USA, and Smithfield Foods – were compelled to suspend production at some 20 slaughterhouses nationwide as a result of rising coronavirus infections, triggering concerns of a mass meat shortage. As it stands, a relatively small number of plants process the vast amount of beef and pork consumed in the United States.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Data released earlier this month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed nearly 5,000 plant workers in 19 states had tested positive for the virus as of April 27, likely due to the close working conditions. The subsequent threat of a meatless America prompted the Trump administration in late April to invoke the Defense Production Act, which ultimately mandates that the processing facilities remain open throughout the crisis.

Massie highlighted that the problems plaguing the meat industry are going to last a long time, and while the PRIME Bill is far from "a silver bullet" solution, it would put scores of farming families back in business within weeks.

"Millions of hogs are being wasted, (farmers) are having to put them in wood chippers with the wood, so they compost quicker," he lamented, highlighting that it is far more beneficial to fix the process than to come up with solutions regarding how to dispose of the animals, given that coronavirus has ignited flagrant problems in the meat supply chain.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

Moreover, Daren Bakst, a senior research fellow in agricultural policy at the Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation, said that the PRIME bill would thus "help provide another means of selling meat to American families and businesses, promote competition, and could also reduce costs for smaller farmers who find it challenging to get their animals to USDA-inspected processing facilities.

"Every little bit helps, and by reducing the unwarranted federal intrusion into agriculture, the market might adjust and create a new and possibly significant way of purchasing meat," he said. "The coronavirus and recent weather disasters have highlighted the failings of our subsidy system."

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Small farmers say that they remain casualties of the 1967 Wholesome Meat Act, which mandates that slaughterhouses can only produce meat for sale if they have a federal inspector on-site during slaughtering or are in a state with its own stringent standards. This law was passed at a time when there were around 10,000 slaughterhouses across the United States, but the rigorous regulations over time have made it harder for small-scale operations to keep up. U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA) data shows now that there are fewer than 2,800 slaughterhouses in operation nationwide.

A shopper browses in the meat department at a supermarket in Princeton, Ill., on Thursday, April 16, 2020. The Trump administration would like to make purchases of milk and meat products as part of a $15.5 billion initial aid package to farmers rattled by the coronavirus, said Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue. Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The current law does have exemptions for the slaughter of animals from federal inspection regulations, "but only if the meat is slaughtered for personal, non-paying household guests, and employees." Thus, in order to sell individual cuts of locally raised meats to consumers, farmers and ranchers must first send their animals to one of a limited number of USDA-inspected slaughterhouses.

While the term "inspected" refers to federal oversight, smaller farms often fall under the "custom" designation, which is primarily used by people with the means to take their own animals to an abattoir for processing.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}However, the bill has struggled since its 2015 introduction as a result of steep concerns over food safety should inspection requirements be eased and is primarily opposed by the major companies and the USDA. For one, the National Pork Producers Council has a statement opposing the bill, underscoring that "a robust and consistent U.S. meat inspection system is critical to ensuring food safety, maintaining consumer confidence and safeguarding animal health."

"Currently, this is achieved by requiring that FSIS or a fully equivalent state program provide ante- and post-mortem inspection of all meat products produced and sold commercially in the United States," the council states. "The PRIME Act would allow states to modify their laws to allow for the intrastate sale of non-inspected meat products."

According to Mary Hendrickson, associate professor of rural sociology at the University of Missouri, if PRIME were to be signed into law, some custom-exempt facilities may be able to transition from meat intended for individual households to meat slaughtered and processed for widespread intrastate trade – that is, sell to grocery stores, restaurants, and hotels – but such a transition raises real concerns about compliance with the Humane Slaughter Act of 1978.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}"Because no inspector is present, as well as food safety concerns for the general public...there is limited sanitation oversight," she noted. "Instead, we should find ways to use the important infrastructure these small plants represent and provide policies and investments that would help them expand their facilities that could then better serve regionally-based markets."

And Vincent Smith, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), concurred that the pending legislation would no doubt face tough opposition from the meatpacking industry, food safety groups, and both USDA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

"Large-scale ranch operations, which generate over 80 percent of all cattle, are also likely to be concerned. The reason is straightforward; the potential health risks posed by small scale butchering operations that effectively are subject to no inspection and that supply meat to consumers who pay for the products are substantial," he stressed. "Not all small-scale operators will follow hygienic practices or pay attention to the health of the animals being slaughtered, even though most will. The potential incidence of serious health problems deriving from such meat would create significant problems for the entire industry, not just the small-scale operators."

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}SEATTLE, WASHINGTON - MARCH 10: The Pike Place Market stands virtually empty of patrons on March 10, 2020 in downtown Seattle, Washington. The historic farmer's market is Seattle's most popular tourist attraction, and business has been especially hard hit by coronavirus fears. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Massie conjectured that the predominant requirement is that an animal is ambulatory – meaning that it can walk – prior to being slaughtered for consumption, and a possible solution could be for farmers would be to film every animal coming in or for it be live-streamed and observed by a USDA inspector.

"These inspectors are watching hundreds of animals at facilities," he continued. "Why couldn't they do this for smaller farms?"

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}But whether such a solution would suffice remains to be seen. Massie also pre-empted that another criticism of the bill is that it could potentially run afoul of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, raising concerns that the standards for meat processed within the U.S. are different than the standards for imported meats – and problem-solving there might be a little more complicated.

"Put America First," Massie added. "Here is the irony, these regulations have only enriched the Chinese and Brazilian companies that have come to control so much of our meatpacking."

The USDA and FDA did not respond to requests for comment.