Judge rules Philadelphia supervised injection site does not violate federal law

Community members react to federal judge’s decision to ok safe injection center in Kensington

PHILADELPHIA – Roz Pichardo, 41, who carries naloxone with her everywhere she goes, says she has reversed 186 overdoses while traversing the city. The drug epidemic is so bad where she lives, she said, that there are people shooting up on her front yard.

"It's devastating," Pichardo said. "We used to have dine-in restaurants and family-owned businesses, now our kids are stepping over syringes. I want a clean neighborhood for them.”

Philadelphia has become one of the epicenters of the opioid crisis, with the city estimating there were 3,191 overdose deaths from 2016 to 2018. In Kensington, the hardest-hit community in the city, entire blocks have turned into homeless encampments for addicts, community playgrounds have been forced to add sharp boxes, and bus terminal have closed out of fear of drug activity.

Now, a recent ruling could clear the way for Philadelphia to have the first supervised injection site in the nation -- much to the chagrin of the federal government. The city hopes the site will alleviate the city's drug problem, but the federal government equates it to a legalized crack house.

PHILADELPHIA AIMS TO BECOME FIRST US CITY TO LEGALIZE SAFE INJECTION SITES

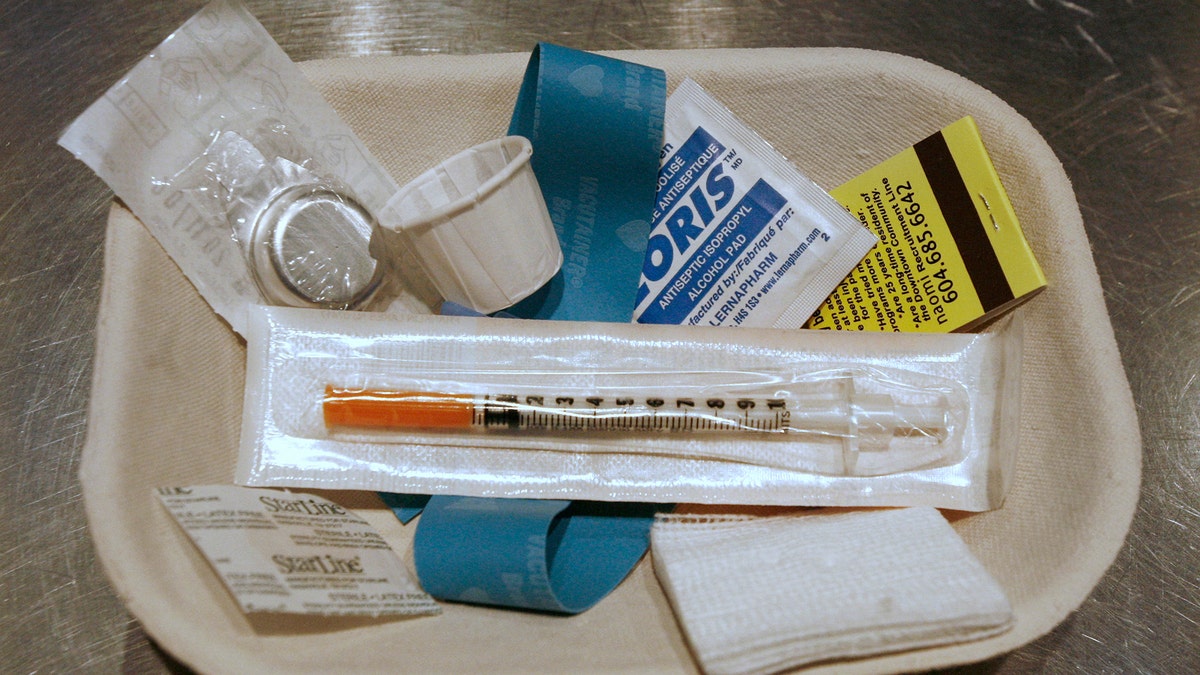

The highly contested site, which would be operated by a local non-profit called Safehouse, would give drug addicts a safe haven to consume and would offer sterile injection equipment, including needles, and Naloxone. It would also give referrals to treatment centers, social services, housing and wound care facilities.

Roz Pichardo, 41, wears a fanny pack every day. In it, she carries her cellphone, a small bible, and naloxone. Pichardo is a “zero responder,” or a bystander who steps in to reverse the effects of an overdose before medical professionals get to the scene. (Fox News)

Cities across the United States, including Denver, Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, and New York, have considered opening such facilities but have been stymied by the federal law and the Justice Department’s vow to halt any project of its kind.

Philadelphia has decided to move forward, with the support of city officials and former governor Ed Rendell, who sits on its board. But the facility's future is still uncertain because the Justice Department has continued its effort to stop the project, and sued the city in February.

“They are in legal nomads land,” said Robert Field, professor of law and public health at Drexel University.

OHIO CORONER SAYS OPIOID CRISIS IS 'NOT GOING AWAY' AFTER 10 DEATHS IN HER COUNTY IN JUST OVER A DAY

Last week, a judge ruled that the proposed site does not violate federal law -- an unprecedented decision. U.S. District Judge Gerald A. McHugh wrote that a provision of the Controlled Substances Act aimed at closing crack houses does not apply to the nonprofit organization’s bid to aid opioid abusers in Philadelphia’s drug-ravaged Kensington section.

The sites would give drug addicts a safe haven to shoot up and would offer sterile injection equipment, including needles, and Naloxone. It would also give referrals to treatment centers, social services clinics and wound care facilities. (REUTERS, File)

The “crack house statute,” which became law in the 1980s -- at the height of the crack epidemic -- makes it a felony to knowingly open, lease, rent, use, or maintain any place for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.

“The ultimate goal of Safehouse’s proposed operation is to reduce drug use, not facilitate it,” the judge wrote.

“We were gratified to see the judge's decision. It’s 56 pages of really thoughtful reasoning," said Ronda Goldfein, Safehouse’s vice president and the director of the AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania. “We always knew that it couldn't possibly be illegal to try to save people's lives.”

Goldfein said it is not clear how soon Safehouse might be able to open.

“The judge’s decision is not a final judgment but lays the groundwork for us to move forward,” Goldfein said.

When a final decision is issued, the government could again seek to block the project and McHugh and an appellate court would both have to decide whether to allow it, she said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey A. Rosen vowed to continue opposing the site.

“The Department is disappointed in the Court’s ruling and will take all available steps to pursue further judicial review," Rosen said in a statement. "Any attempt to open illicit drug injection sites in other jurisdictions while this case is pending will continue to be met with immediate action by the department.”

Goldfein says while she respects the position of the U.S. attorney general, her organization disagrees, citing success in other countries and ongoing research to support her position.

“I think Safehouse is clearly a public health initiative, and we are hoping a final order will declare the site legal,” said Goldfein.

Canada and Europe have operated similar types of facilities for the last few decades, which advocates and researchers claim have saved thousands of opioid-dependent individuals by directing them into treatment.

Typically, users bring in drugs obtained on the street and are monitored as they inject or smoke the drugs to prevent overdoses. Medical professionals on site are equipped with naloxone to reverse overdoses and can provide clean syringes, matches for cooking heroin, elastic strips to tie off veins, water to dilute drugs and other provisions.

An injectable drug is loaded into a syringe while the prescription medication is strewn about haphazardly. (Getty Images, File)

But the program has also been met with resistance by residents who fear it will exasperate the city's already devastating drug problem.

“I worry this will only increase the problem, and we will see people traveling down I-95 to get a hold of more drugs,” said Tina, a longtime Kensington resident who said she doesn't want people traveling into her community to do drugs.

Safehouse’s organizers still must address several concerns before they can open their facility. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Mayor Jim Kenney has suggested the city develop a policing plan before opening a site. And most importantly, a location must be publicly announced.

For Pichardo, who has already lost one loved one to an opioid overdoes, she said she is willing to try anything to see her community and family safe.

“My cousin is out there still using and I fear I will get the call to come to rescue him," Pichardo said, "or worse, I won’t get the call and he will die alone because he doesn’t have a safe place to go.”