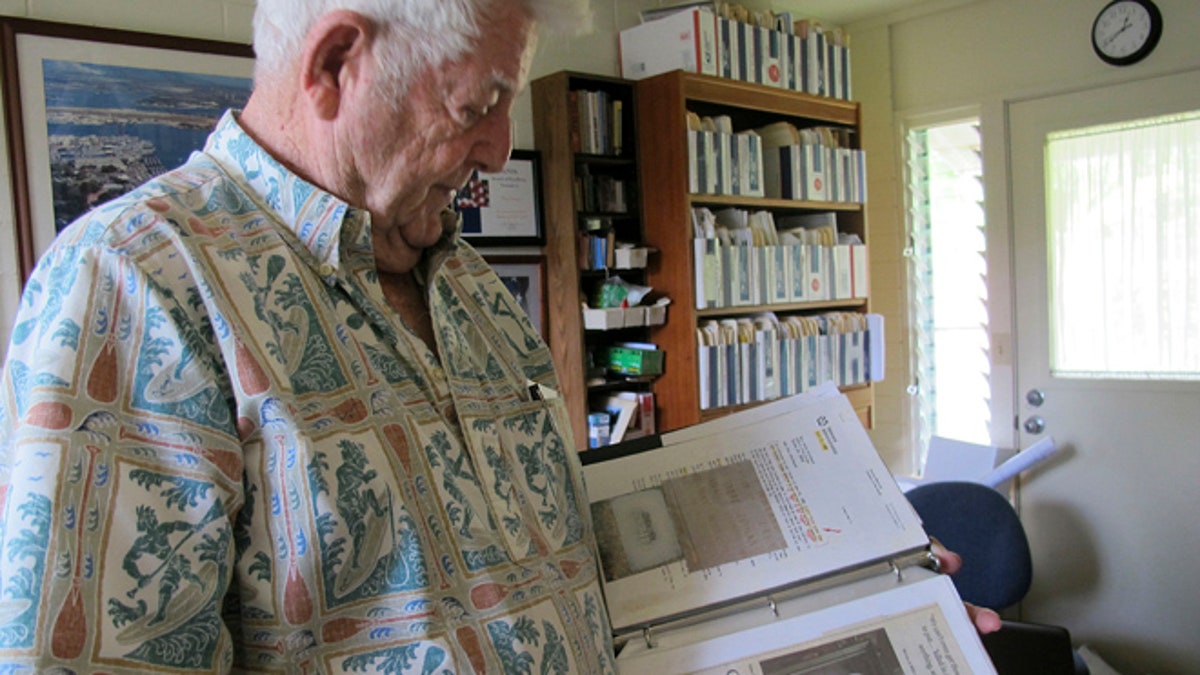

Nov. 21, 2012: Ray Emory discusses his work pushing to change grave markers for unknown Pearl Harbor dead and identifying the remains of unknowns at his home in Honolulu. (AP)

HONOLULU – Ray Emory could not accept that more than one quarter of the 2,400 Americans who died at Pearl Harbor were buried, unidentified, in a volcanic crater.

And so he set out to restore names to the dead.

Emory, a survivor of the attack, doggedly scoured decades-old documents to piece together who was who. He pushed, and sometimes badgered, the government into relabeling more than 300 gravestones with the ship names of the deceased. And he lobbied for forensic scientists to exhume the skeletons of those who might be identified.

On Friday, the 71-year anniversary of the Japanese attack, the Navy and National Park Service will honor the 91-year-old former sailor for his determination to have Pearl Harbor remembered, and remembered accurately.

"Some of the time, we suffered criticism from Ray and sometimes it was personally directed at me. And I think it was all for the better," said National Park Service historian Daniel Martinez. "It made us rethink things. It wasn't viewed by me as personal, but a reminder of how you need to sharpen your pencil when you recall these events and the people and what's important."

Emory first learned of the unknown graves more than 20 years ago when he visited the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific shortly before the 50th anniversary of the attack. The grounds foreman told him the Pearl Harbor dead were scattered around the veterans' graveyard in a volcanic crater called Punchbowl after its resemblance to the serving dish.

Emory got a clipboard and walked along row after row of flat granite markers, making notes of any listing death around Dec. 7, 1941. He got ahold of the Navy's burial records from archives in Washington and determined which ships the dead in each grave were from.

He wrote the government asking why the markers didn't note ship names and asked them to change it.

"They politely told me to go you-know-where," Emory told The Associated Press in an interview at his Honolulu home, where he keeps a "war room" packed with documents, charts and maps. Military and veterans policy called for changing grave markers only if remains are identified, an inscription is mistaken or a marker is damaged.

Emory appealed to the late Patsy Mink, a Hawaii congresswoman who inserted a provision in an appropriations bill requiring Veterans Affairs to include "USS Arizona" on gravestones of unknowns from that battleship.

Today, unknowns from other vessels like the USS Oklahoma and USS West Virginia, also have new markers.

Some of the dead, like those turned to ash, will likely never be identified. But Emory knew some could be.

The Navy's 1941 burial records noted one body, burned and floating in the harbor, was found wearing shorts with the name "Livingston." Only two men named Livingston were assigned to Pearl Harbor at the time, and one of the two was accounted for. Emory suspected the body was the other Livingston.

Government forensic scientists exhumed him. Dental records, a skeletal analysis and circumstantial evidence confirmed Emory's suspicions. The remains belonged to Alfred Livingston, a 23-year-old fireman first class assigned to the USS Oklahoma.

Livingston's nephew, Ken Livingston, said his uncle and his father were raised together by their grandmother and attended the same one-room schoolhouse. They grew up working on farms in and around Worthington, Ind. Livingston remembers his dad saying the brothers took turns wearing a pair of shoes they shared.

When the family learned Alfred was found, they brought him home from Hawaii to be buried in the same cemetery where his grandmother and mother rest.

About a third of the town showed up for his 2007 memorial service in Worthington, a town of just 1,400 about 80 miles southwest of Indianapolis. The local American Legion put up a sign welcoming home "Worthington's missing son."

"It brought a lot of closure," said Ken Livingston, 62, his voice cracking.

John Lewis, a retired Navy captain who worked with Emory while assigned to the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command between 2001 and 2004, said the command is fortunate someone like Emory has the time and initiative to painstakingly connect the dots on the unknowns.

"Without Ray Emory I don't know if this ever would have been done," Lewis said from Flowood, Miss.

Emory says people sometimes ask him why he's spending so much time on events from 70 years ago. He tells them to talk to the relatives to see if they want the unknowns identified.

He doesn't get emotional about the work, except when the government doesn't exhume people he thinks should be dug up and identified.

"I get more emotional when they don't do something," he said.

He'll keep working after he's formally recognized during the Pearl Harbor ceremony on Friday to remember and honor the dead. He has names of 100 more men buried at Punchbowl he believes are identifiable.