RALEIGH, N.C. – Three weeks after the deadliest attempted prison breakout in North Carolina history, prison and law enforcement officials still can't quantify the scope of the violence that correctional officers at the understaffed prison had been confronting daily.

A fourth Pasquotank Correctional Institution worker injured in the failed Oct. 12 breakout died Thursday. State prison officials say they don't yet know how many employees or inmates at Pasquotank have been injured by violence in the past year.

Nor are they able to say how many prison workers have been assaulted at other prisons across the state since the escape attempt. At least one correctional officer was injured when she was attacked last week by an inmate at North Carolina's primary women's prison in Raleigh.

Records of on-the-job injuries suffered by prison workers aren't tracked by wardens of individual lockups and are instead kept in a central database, state prisons spokesman Jerry Higgins said Thursday.

"The request has been made to our data people here for these numbers, for this information. It's kept in a central location, not at the prisons," Higgins said. "We are still waiting to receive the information from our data people. No one's dragging their feet."

The public has a right to know more about attacks on prison workers, Gov. Roy Cooper said Thursday.

"It has been appalling what has happened to these fine correction officers. Their safety needs to be a priority for us," Cooper said after an appearance in Raleigh. "The public does have a right to know what's happening in our prisons and we're going to work to have a reform process in place that is responsive and that solves the problem."

Meanwhile, the Pasquotank County Sheriff's Office, which is investigating crimes committed during last month's failed breakout, has been unable to say how many cases of violent assault detectives have investigated in the past year. Investigators charged one inmate with stabbing another in April.

The Associated Press requested the data from the sheriff and state prison authorities the day after the Elizabeth City prison's failed escape, in which two correctional officers, vocational instructor Veronica Darden and maintenance worker Geoffrey Howe died. Four inmates are charged with murder after they were accused of setting a fire as a diversion, attacking the workers and scrambling to scale the prison's fence.

An internal Correction Department report says the attempted escape lasted 43 minutes from the time two inmates attacked Darden until the last inmate surrendered upon making it over a series of obstacles to the outermost fence. Justin Smith, the correctional officer guarding the sewing shop where the inmates worked, died after being battered with a claw hammer, said the report, which was first acquired by Charlotte TV station WBTV.

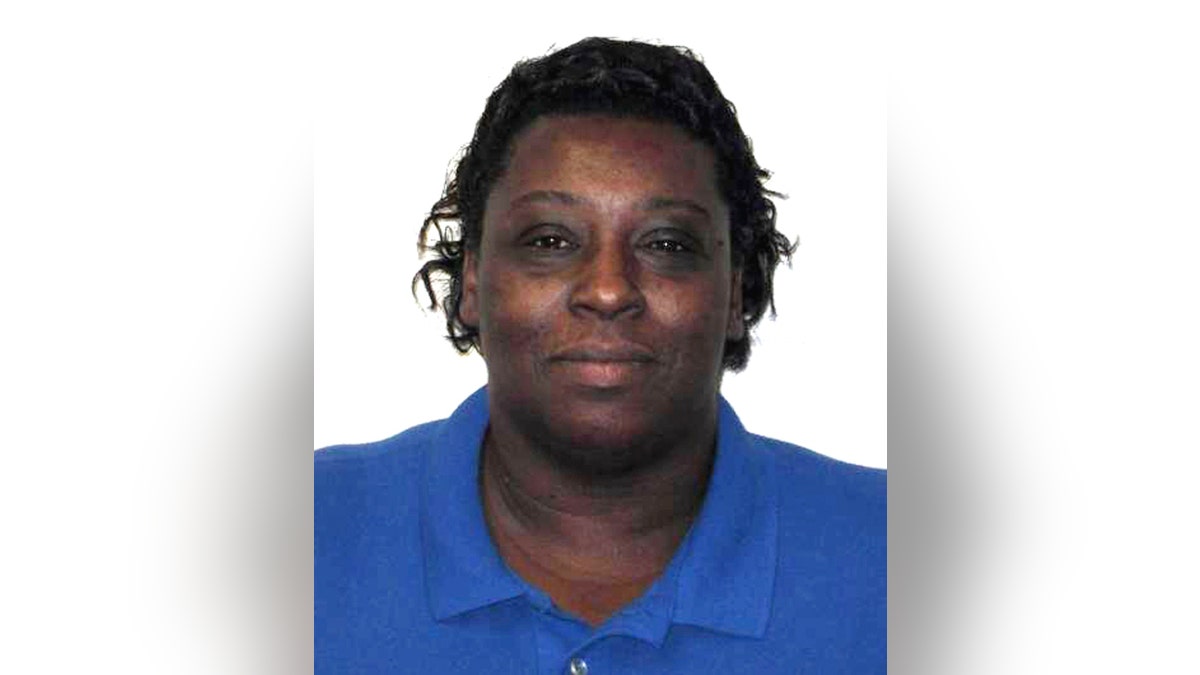

Correctional Officer Wendy Shannon died Monday. She and a guard who survived were attacked in a loading dock by the inmates tugging carts of "tools and supplies needed for their escape attempt," the report said.

Smith was the only correctional officer supervising more than 30 inmates in the prison's sewing plant, ground zero for the attack, where inmates worked with cutting sheers and screwdrivers, State Employees Association of North Carolina President Stanley Drewery said.

The Pasquotank case is the worst example of troubling staffing conditions in North Carolina, said Drewery, the head of the 55,000-member public employee union. He says a prison employee is assaulted every eight hours, on average, in the state. Correctional officials have not disputed the statistic.

An attack "could happen at any given prison at any given time, even fully staffed. But when you're understaffed, that makes it more hazardous," said Drewery, himself a former prison officer who retired in 2012.

Across the statewide prison system, about one out of seven of the correctional officer jobs were unfilled in September, based on Correction Department records provided to SEANC.

But finding enough correctional officers to meet security needs is harder for prisons in rural areas like Pasquotank and nearby Bertie Correctional Institution, where a guard was beaten to death in April.

Pasquotank was 28 percent short of its full complement of 266 correctional officers around the time of last month's attack, according to Correction Department figures. Bertie had a 26 percent vacancy rate for correctional officer spots. Hyde Correctional Institution, also in the state's rural northeast corner, was missing 38 percent of its assigned staffing level for guards.

___

Follow Emery P. Dalesio on Twitter at http://twitter.com/emerydalesio. His work can be found at https://apnews.com/search/emery%20dalesio

___

Associated Press writer Gary Robertson contributed to this report.