Blue Lives Lost: Remembering Kyle Olinger (1966 - 2019)

Officer Kyle Olinger succumbed to complications of a gunshot wound sustained on August 13, 2003, while making a traffic stop on April 18th. Olinger had served with the Marines and was working toward his doctorate. He had served with the Montgomery County Police Department in Maryland for two years and had previously served with the Reading Police Department for six years.

More than a decade since he was left paralyzed from the chest down -- the result of a bullet fired by an 18-year-old who was a passenger in a car he had stopped -- retired Montgomery County Police Officer Kyle Olinger wrote a long post on Facebook to say that, despite what he often heard, he was not a hero.

The former Maryland cop also wanted people to understand the complex swirl of thoughts, instincts and second-guessing that can grip a police officer in that second when possible death stares at you through the eyes of someone who exudes an utter disregard for life.

CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE COVERAGE OF 'BLUE LIVES LOST'

“I have been second-guessed and ‘Monday morning quarterbacked’ by a few who never got the whole story, and believed I screwed up,” Olinger, a former Marine, said of the 2003 incident. “I have been hailed as a hero by others, and was awarded the Medal of Valor for nothing more than getting shot and falling down.”

Olinger lamented that his shooter, Terrence Arthur Green, who was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to life in prison, most likely would outlive him.

Unfortunately, he was right. Olinger died at the age of 53 on April 18 of complications from that gunshot. It's unclear whether Green's charges will be upgraded to murder.

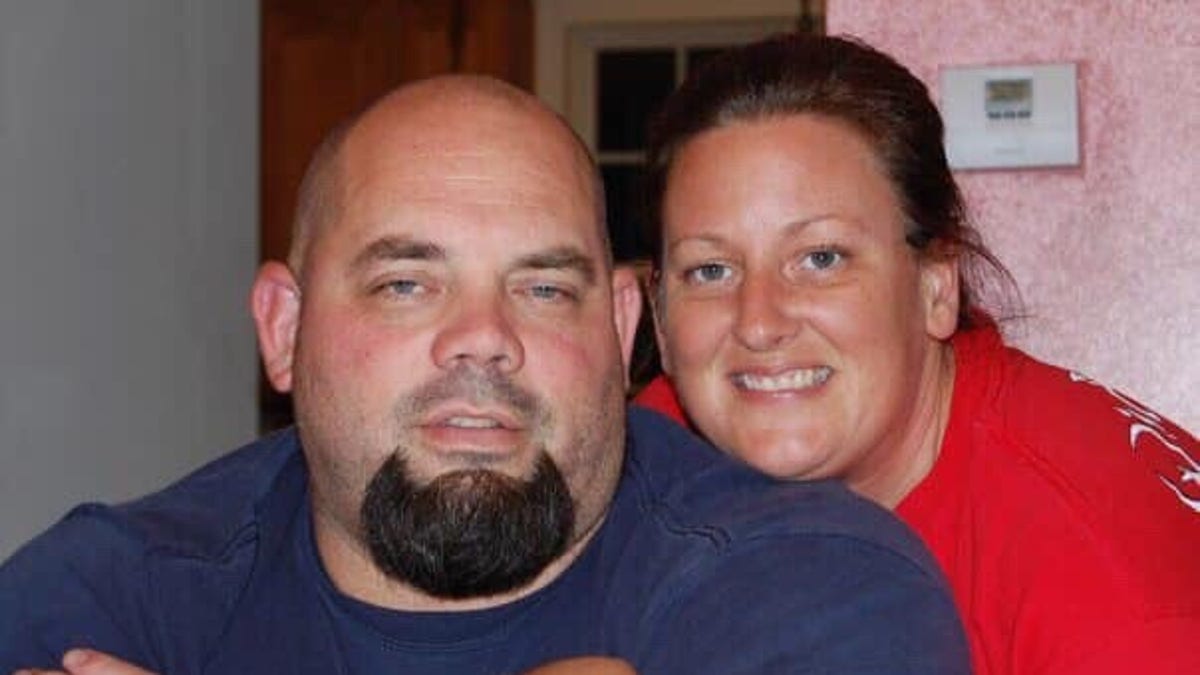

Montgomery County (Maryland) Police Officer Kyle Olinger with his wife, Jeana.

OFFICERS KILLED IN THE LINE OF DUTY IN 2019

“He wanted to write his own story about his life and the events of that night,” said his friend and former fellow officer, Rodney Cox. “Kyle’s situation is unique because when an officer is killed in the line of duty, we don’t know the story of what happened from their perspective.”

Former Montgomery County (Maryland) Police Department Officer Kyle Olinger, who died on April 18 from health problems brought on by a gunshot wound sustained in 2003. The shooting, which occurred during a traffic stop, left Olinger paralyzed from the chest down.

“He had so many years to be with this injury, to live with it, to suffer through it and all the complications that came with it,” Cox said. “He wrote it as much for himself as well as everyone else.”

After Olinger’s death, the former Montgomery County state attorney who prosecuted the gunman recalled how, even as Olinger lay on the ground, critically wounded and unable to feel his lower body, the officer repeatedly expressed concern for his son.

Olinger’s life – even before the shooting – had its share of adversity, as he recounted in the unvarnished Facebook post.

For much of his son’s life, he was a single father who strove to find a balance between the demands of his police work and parental responsibilities. His first wife tired of his absence during deployments, and left him and their son. His second marriage fell apart after his wife started working for the FBI and the two grew apart.

“My son had lost a second mother, and was acting out, and on top of that I had to leave him home alone to fend for himself while I worked,” he wrote.

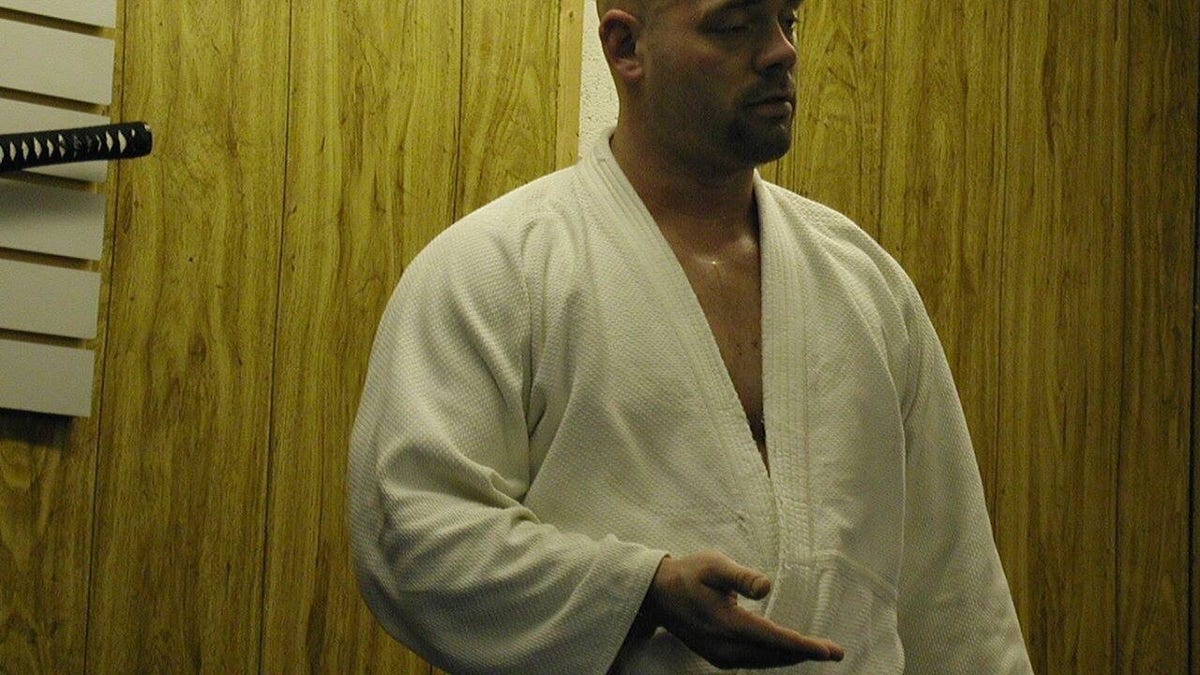

Before he was left paralyzed by a gunman while responding to a call, Maryland County Police Officer Kyle Olinger was active in martial arts.

Olinger recalled one incident in which he provided back-up support to officers who responded to a stolen car call. Olinger found himself alone with two suspects who’d taken off on foot, and saw one of them reach into his pocket. Olinger said he might have shot him if not for concern about possible bystanders nearby who would have been in the crossfire. When another officer showed up, he and Olinger got control of both suspects, and Olinger discovered that the one who’d reached into his pocket was trying to grab drugs he was carrying.

“He was only 13 or 14 years old, and it really shook me up that I had come so close to killing him over a bag of weed,” Olinger wrote. “My own son was just 14 years old at the time.”

That incident stayed in the back of his mind when he came face to face with the men in the car he'd just stopped in August 2003, he said. When a man on the passenger’s side went for a gun he tried to hide under the seat, Olinger tried to stop him, but the man shot the officer in the neck, paralyzing him for life.

Olinger theorized in his post that fear of shooting a young black man – and igniting tensions --might have played a role in his decision not to use force before the passenger grabbed his gun.

“He could have chosen deadly force,” Cox said, “and he chose to continue to give verbal commands, he chose to give the man the chance to surrender.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Cox said Olinger somehow managed to remain philosophical and determined to continue developing goals and striving to reach them. He returned to school and got certified in acupuncture, and was determined to walk again, if there could ever be a way.

“He was never able to get there,” Cox said of Olinger’s hope that he could walk once more. “His health declined.”

And yet, Cox said, “Kyle was very much a warrior in the remainder of his life."