Mississippi farmer struggling after widespread flooding ruins planting season

Heavy rains flooded more than a million acres of land during what was supposed to be planting season for crops such as soybeans, cotton, and corn.

ROLLING FORK, Miss. -- The time to get crops like soy beans, cotton and corn in the ground have come and gone for many farmers in the Mississippi Delta. Months of flooding from record rainfall and backed up waterways, which were shut off from draining into the Mississippi River, has flooded more than a million acres of land and squandered away the growing season.

The thought of starting over has crossed the mind of farmer Parker Adcock, 25, consistently. He stood and exhaled slowly as he looked around his home that he, his pregnant wife and their young daughter were displaced from after 10 inches of floodwater moved in this spring. The water is out of the home; however, it now sits infested with mold and insects of all sorts.

“The first time we came back and saw this, I was in tears looking at all of this,” he said. “If you’re not tied to the land, I’d be getting out.”

Parker Adcock, 25, and his family stand in front of their home. They were forced out of the home six weeks after moving in when 10 inches of water flooded it. (Fox News/ Charles Watson)

Leaving isn’t an option for the young farmer. He’s committed to 4,000 acres of farmland (about 6 square miles), most of which is left useless this year as it sits in slow-receding floodwater. He’s been able to plant some corn crops on about 175 acres -- about 4 percent of his land -- but it won’t yield him nearly enough to get him through the year.

The 25-year-old estimates his damages will total somewhere in the 7-figure range after his property damage is assessed; and even though his financial means have vanished for the year, his operational costs have not.

HURT BY US-CHINA TRADE WAR IOWA FARMERS HOPE HEMP IS THERE BIG MONEY SAVIOR

“Land owners still want their rent money, regardless of whether I made a crop or not. John Deere still wants to get paid for the tractor sitting in the shed that I never got to pull out for the year,” he said. “I have to figure out a way to come with all that and still be able to farm again next year.”

In May, Billy Whitten had been hopeful that the floodwater that had inundated more than a million acres of land in the Mississippi Delta would be gone by now. He and others hoped they would be able to get some crops planted this season. That hope has dissipated as most of his 1,400-acre farm in Valley Park, Miss. is drowning in water.

“There’s no way we can plant anything this year,” Whitten said. “It’s past the planting time.”

Farmer Billy Whitten stares out at his 1,400 acres of farmland that he won't be able to plant on this year. It now resembles a lake as it drowns in slow-receding floodwater. (Fox News/ Charles Watson)

Aside from his duties on his own farm, Whitten sits on the board of the Valley Park Grain Elevator. The elevator buys grain harvested buy local farmers, stockpiles it and then later sells it. However, business has been down by as much as 75 percent this year.

The 10-member board has done what it can to make sure its employees have had a source of income, but it’s getting to a point where tough business decisions are going to have to be made.

“We’ve got several employees that work there. We’re hoping that we won’t have to lay any of them off, but it’s a good chance some of them will lose their job because of this.”

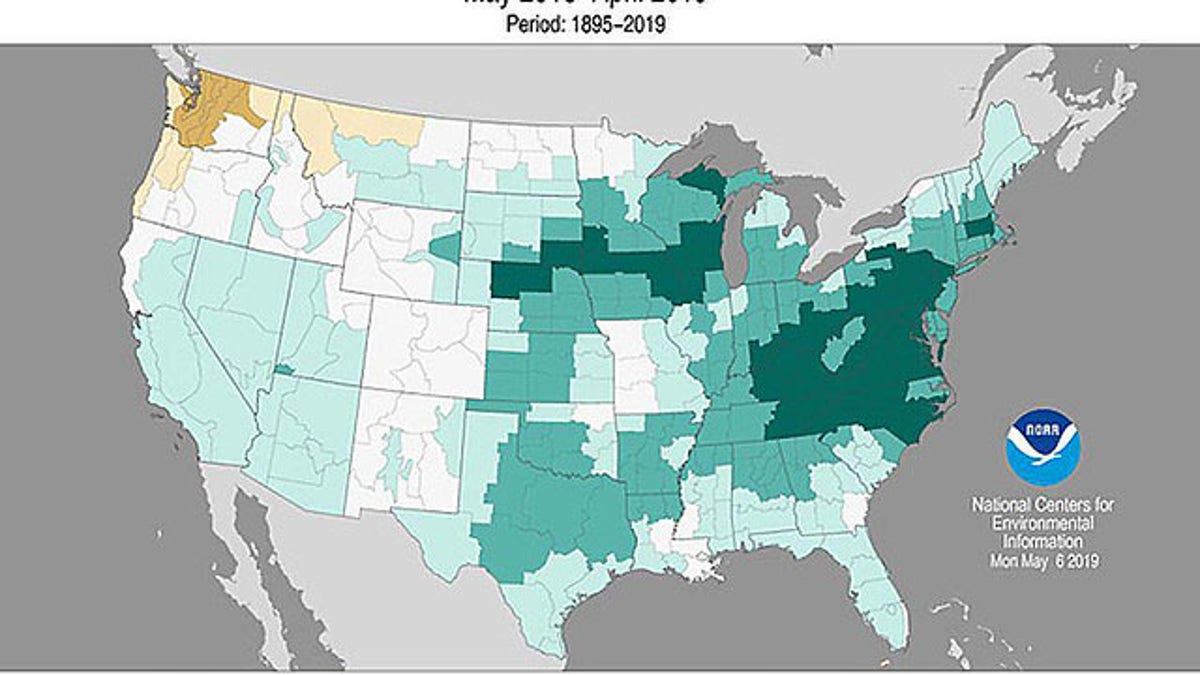

Rain and flooding have been a struggle for farmers across the country this year. From March 2018 to April 2019, an average of 36.20 inches of rain fell across the Lower 48 states -- the nation’s wettest 12-month period on record, according to the USDA.

A map from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration illustrating areas of the country has above average or record rainfall between March 2018 and April 2019. (NOAA)

Corn and soybean crops have taken a hit as a result of the record precipitation. U.S. corn planting failed to reach the halfway mark by mid-May this year. For the first time on record, less than 50 percent of intended corn crops had been planted. Comparably, the USDA reported 19 percent of U.S. crops had been planted during the same time period -- the lowest amount for soybeans since 1996.

Mike McCormick, president of Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation, said the difference between other farm communities that border the Mississippi River are pumps. There is no system in place to pump water out of the Mississippi Delta during record rain and flood events like this year.

TROPICAL STORM BARRY TESTS LOUISIANA'S MULTI-BILLION DOLLAR POST-KATRINA FLOOD DEFENSES

“It’s a chronic event for us. 41 percent of the United States is drained right by our border here in Mississippi. Because of the record amount of rainfall, we’re having, we’ve basically turned Mississippi into a flood control structure for the rest of the United States,” McCormick said. “We definitely need the pumps to help the south Delta, but we also need a new plan on the Mississippi River and how we’re going to drain it.”

The Environmental Protection Agency had planned on installing pumps in the region, but the project was vetoed in 2008. It told Fox News in a statement that it is actively looking for solutions.

"EPA recognizes and is very concerned with the significant and disruptive impacts of the recent flooding to Mississippians and to the State’s Economy," the agency said in a statement, adding it had met with various officials to come up with way to address the issues.

Adcock is trying to look ahead to the future. But his anxiety, due to this year’s flood event, is so high he’s having nightmares where he’s surrounded by water.

“It’s been mentally exhausting,” he said. “If this happens again, I’m done. Nobody can survive two years of this.”