Shown at left, Fort Leavenworth; at right, Guantanamo Bay. (AP)

The Obama administration is emptying the military’s Guantanamo Bay detention facility of avowed terrorists captured fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, but several American service members languish in another military prison for actions on those same battlefields that their supporters say merit clemency, if not gratitude.

Among the prison population at Fort Leavenworth, in Kansas, are remaining members of the so-called “Leavenworth 10,” convicted service members doing terms ranging from 10 to 40 years for heat-of-the-battle decisions their supporters say saved American lives.

“The very people who protect our freedoms and liberties are having their own freedoms and liberties taken away,” said retired U.S. Army Col. Allen West, a former congressman and political commentator. “I think it’s appalling and no one is talking about this issue."

The "Leavenworth 10" is the name given to a fluctuating number of men housed at Leavenworth for actions in Iraq and Afghanistan that their supporters say were justified. Over the years, a handful have been paroled, and more have been incarcerated.

Among the more well-known cases is that of Army First Lt. Clint Lorance, who is serving a 20-year sentence for ordering his men to shoot two suspected Taliban scouts in July 2012 in the Kandahar Province of Afghanistan. Lorance had just taken command of the platoon after the prior leader and several others were killed days before. The Taliban suspects were on motorcycles and matched descriptions given by a pilot who flew over the area earlier and spotted them as scouts.

“The very people who protect our freedoms and liberties are having their own freedoms and liberties taken away.”

A Facebook page devoted to Lorance’s case has drawn more than 12,000 likes, and supporters have launched a website, FreeClintLorance.com, dedicated to winning his release. A WhiteHouse.gov petition calling for Lorance to be pardoned garnered nearly 125,000 signatures, but the White House has not taken action.

Critics say Lorance was given a military trial, and his conviction was based in large part on the testimony of men serving under him.

It was September of 2010 when Sgt. Derrick Miller of Maryland, on a combat mission in a Taliban-held area of Afghanistan, was warned the unit’s base had been penetrated. An Afghan suspected of being an enemy combatant was brought to Miller for interrogation and wound up dead. Miller claimed the suspect tried to grab his gun and that he shot him in self-defense. But he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

1st Lt. Clint Lorance was found guilty of two counts of murder for the July 2012 killing of two suspected Taliban fighters. His defense team argued that the village they were patrolling was under Taliban rule with constant incidents of violence.

U.S. Army Master Sgt. John Hatley -- a highly decorated, 20-year vet who served in Operation Desert Storm and did another three tours during the Iraq War -- also is serving a life sentence at Leavenworth. His conviction stems from an April, 2007, incident in Iraq in which he and his unit captured enemies following a firefight. He radioed a U.S. detention facility to notify officials he was bringing in four prisoners, but was ordered to let them go, according to his legal team.

Two years later, a sergeant who had served with Hatley, Jesse Cunningham, was facing charges for assaulting another officer and falling asleep at his post. As leverage for a plea deal, he told investigators that Hatley and two other officers had taken the insurgents to a remote location, blindfolded them and shot each in the back of the head. He claimed their bodies were dumped in a canal, though none was ever found.

Hatley, now 47, insists he and his men let the insurgents go, but believes he was punished in the interest of the government’s relations with Baghdad.

“When concerns over appeasing a foreign country are allowed to interfere with justice for the purpose of the U.S. government or the military demonstrating that we, the military or the U.S. government will hold our soldiers accountable using a fatally flawed military judicial system, it doesn’t matter what the truth is; it matters only that there is only the appearance of the truth,” he wrote in a message to supporters posted on freeJohnHatley.com.

Law experts say military service members face a daunting task once accused of committing crimes in the heat of war.

“Killing on the battlefield is not the same as [a police officer] killing someone on the streets,” Dan Conway, an attorney who specializes in military law, told FoxNews.com. “When a cop uses force, there’s a line of duty investigation. When a soldier uses force, it is investigated as criminal, and non-infantry investigators handle the case, many who have no combat experience.

“If you had experts handling the investigation, you’d have much more balance,” he added.

While the military rightly holds its soldiers to a high standard of justice, detainees housed at Guantanamo Bay have been freed even with no mitigating circumstances or reasonable belief of rehabilitation. The release of Gitmo detainees began during the presidency of George W. Bush in 2005 when nearly 200 detainees were released before any tribunals were held.

According to a March 2015 memo released by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, of the 647 detainees transferred or released, 17.9 percent were confirmed of re-engaging in extremist activity with another 10.7 percent suspected of doing the same.

The military prison located of the grounds of Fort Leavenworth, Kansas is the largest such facility in the country.

Said Mohammad Alim Shah was repatriated to Afghanistan in March 2004. After his release, he was responsible for kidnapping two Chinese engineers, took credit for a hotel bombing in Islamabad and orchestrated a 2007 suicide attack that left 21 people dead.

Abdullah Ghoffor went back to Afghanistan at the same time and became a high-ranking Taliban commander who planned attacks against U.S. and Afghan forces before being killed in a raid.

Abdallah Salih al-Ajmi, a former detainee from Kuwait, committed a successful suicide attack in Mosul, Iraq, in March 2008. That came three years after he had been freed from Guantanamo and transferred to Kuwait, where a court acquitted him of terrorism charges.

West agrees that U.S. soldiers who commit crimes should be punished severely. But he said the military owes at least as much to men and women who risk their lives fighting for their country as it does to the unrepentant terrorist at Guantanamo Bay.

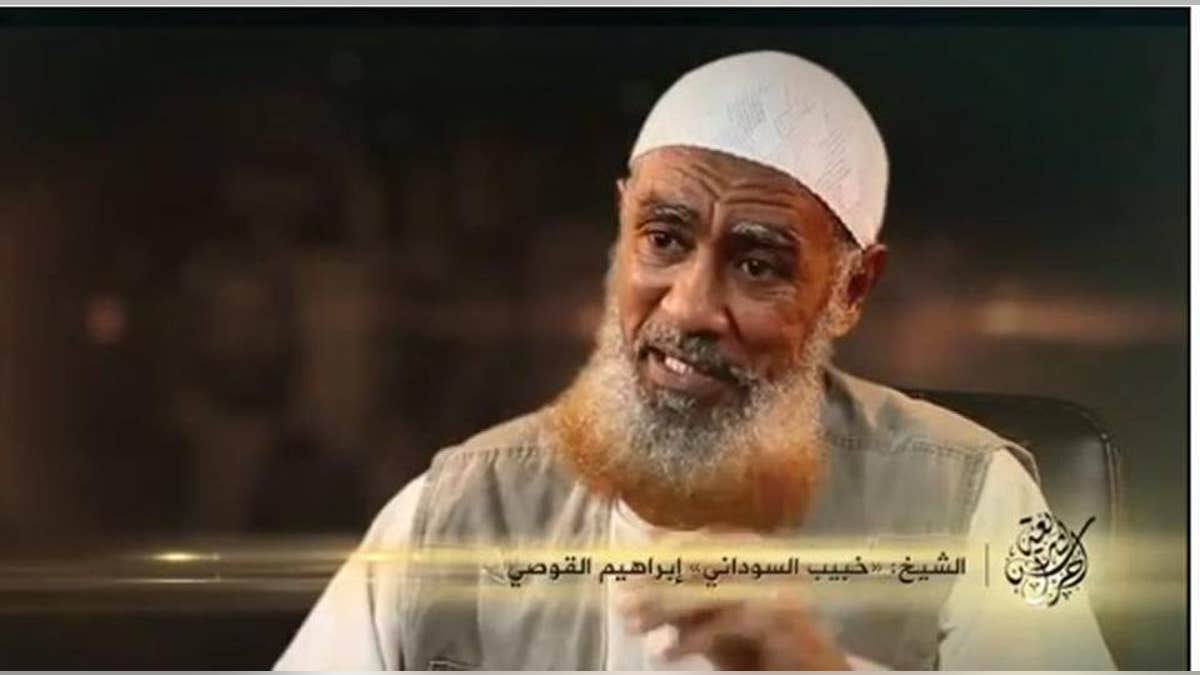

Ibrahim al Qosi spent over a decade at Guantanamo Bay prison before he was released. It is believed that he currently holds a key position of leadership in Al Qaeda of the Arabian Peninsula.

“The rules of engagement should be coming from the bottom up and not the other way around, to protect them against the scores of non-state combatants and enemies,” West said. “Gitmo is seen as this place of recruitment for jihadists and there are those trying to make us believe that Leavenworth is the same.”