Gen. Michael Hayden discusses the terror trend in America

Court documents show significant premeditation by accused bomber; former CIA director provides insight on 'The Kelly File'

Two years after the FBI concluded Ahmad Khan Rahami was not a terrorist, the Afghan immigrant was charged in federal court with using a weapon of mass destruction in a weekend terror attack that injured 31 people.

Rahami, 28, is alleged to have planted pipe and pressure cooker bombs at four locations in New York and New Jersey. When he was arrested Monday morning, authorities found a journal in his possession with entries praising “Brother Usama bin Laden.” He wrote that he prayed to Allah to continue his jihad and achieve martyrdom and also raged against the U.S. government.

Ahmad Khan Rahami is charged in connection with a series of bombings in New York and New Jersey. (AP)

So did Rahami convert overnight or did investigators miss his Islamist leanings in 2014?

“The challenge that the bureau has when they investigate a man like this man is to identify not a criminal, but to try to discover what I would call the ‘not-yet guilty,’” former CIA and NSA director Michael Hayden said on “The Kelly File” on Tuesday. “And that’s a really, really demanding task.”

Rahami’s father, Mohammad, told reporters that he contacted the FBI two years ago after a violent family incident. Mohammad said he told authorities that his son was a terrorist. Investigators were also told Rahami may have been trying to obtain explosives and was “associating with bad people,” according to an FBI statement released Tuesday. But the FBI said Mohammad eventually recanted the claim about his son, and after interviews and database checks, no evidence was found showing Rahami had radicalized.

“If he had been communicating directly with the terrorist organization and the father said ‘Look here’s the email, here’s the phone call, here’s the communication,’ that would be something different that would allow the FBI to get an investigation,” Tim Clemente, an ex-FBI special agent and counterterror expert, said on “Fox & Friends” on Wednesday.

The missed opportunity to nab Rahami before he allegedly bombed a New York City neighborhood is just the latest instance in a string of squandered chances by authorities to identify and stop potential terrorists before they carry out their plots.

The FBI interviewed Pulse nightclub attacker Omar Mateen three times before he shot and killed 49 people on June 12, 2016. Co-workers claimed in 2013 that Mateen said he had connections to Al Qaeda and wanted to be a martyr. But officials concluded Mateen was merely pushing back on anti-Muslim bullying by his colleagues and was not a threat. During the summer of 2014, investigators interviewed Mateen again, this time for his connections to an American-born terrorist who blew himself up in Syria. But Mateen satisfied officials’ questions and he was cleared.

Omar Mateen shot and killed 49 people at a Florida nightclub. (AP)

The FBI ran Mateen’s name through databases and deployed a pair of confidential informants during their investigations. They also temporarily placed him on a terror watch list. But when the investigation ended, so did all surveillance and scrutiny of Mateen.

So when Mateen purchased two guns a week before the Florida attack, no authorities were alerted.

One of the Boston Marathon bombers was under investigation, too, two years before he and his brother placed pressure cooker bombs near the finish line of the 2013 race, killing three and injuring more than 250 others.

Tamerlan Tsarnaev was first flagged by Russian intelligence sources in March 2011. A memorandum to U.S. officials stated that Tsarnaev had been radicalized and was planning to fly to Russia to join an extremist group. But here, counterterror investigators made a host of mistakes, according to an unclassified summary report from the Office of the Inspector General.

The FBI said Tamerlan Tsarnaev, left, and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev killed three people when they bombed the Boston Marathon finish line. (AP)

While some attempts to investigate Tsarnaev, including an in-person interview, did occur, agents never informed local authorities of their concerns; never visited Tsarnaev’s mosque; never interviewed his wife or an ex-girlfriend he had assaulted; never interviewed friends or associates; never asked Tsarnaev about his plans to travel to Russia; and failed to search several major FBI systems.

Even when Tsarnaev traveled to Russia for several months in 2012, his visit “did not prompt additional investigative steps to determine whether he posed a threat to national security.”

Tashfeen Malik passed all background checks when she came to the U.S. in July 2014. (AP)

When Tashfeen Malik arrived in the U.S. from her native Pakistan in July 2014, she was vetted by five U.S. agencies, passed three background checks and had two in-person interviews. None of those safeguards uncovered her pro-Jihad social media presence. That would only be discovered after she and husband Syed Farook shot and killed 14 people at an office holiday party in San Bernardino in December 2015.

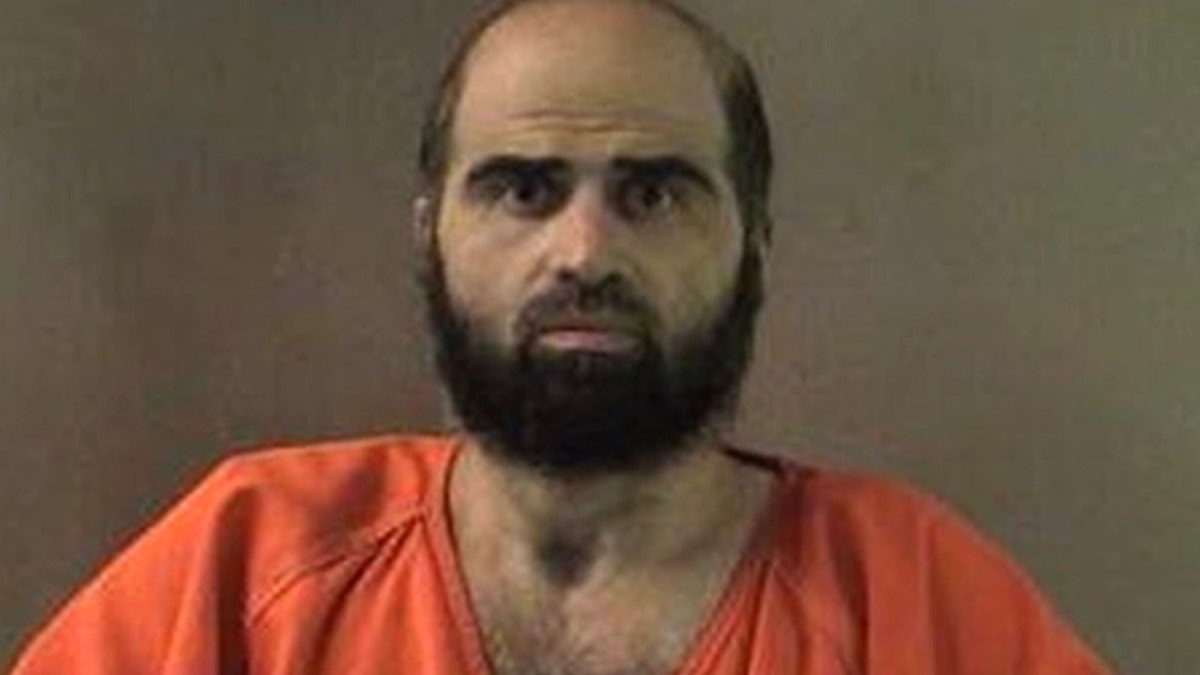

Nidal Hasan killed 13 people at Fort Hood. (AP)

Members of two FBI anti-terrorism task forces knew Army Maj. Nidal Hasan was communicating with terrorist Anwar al-Awlaki via email as early as December 2008, once even asking a question about suicide attacks. But the FBI was concerned about the optics of launching a probe, given that Hasan was an American Muslim in the military, and agents never pursued the case, Rep. Mike McCaul told The Associated Press. On Nov. 5, 2009, Hasan shot and killed 13 people at Fort Hood in Texas.

Federal authorities had been keeping an eye on Wasil Farooqui for some time when he allegedly injured two people in Virginia during an August 2016 knife attack. He reportedly shouted “Allahu Akbar” during the assault and may have been trying to behead his targets. Farooqui made a trip to Turkey sometime during the year before the attack and may have tried to sneak into Syria to join ISIS, sources told ABC.

Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez shot and killed five people in Chattanooga. (AP)

The father of Muhammad Youssef Abdulazeez was on a terror watch list, was questioned about a trip abroad and was investigated for possible ties to a foreign terror group, The New York Times reported. But officials never keyed in on the man’s son, and, on July 16, 2015, Abdulazeez opened fire on several military targets in Chattanooga, killing four Marines and a Navy sailor.

Part of the problem may be bureaucratic constraints.

A preliminary investigation can last six months and be extended for six more. During this period, agents can search databases, conduct surveillance and ask for cellphone records, The LA Times reported. But to use more aggressive and advanced techniques, the FBI would have to open a full investigation and convince a court that there is evidence of a crime.

“We may be bumping up against some of the limits of what is possible,” Hayden said.

Another issue is the sheer volume of tips flowing to authorities. FBI Director James Comey has said there are more than 1,000 active terror investigations taking place in all 50 states.

Clemente also places the blame on the PC culture.

“The fact that we can’t even look at somebody’s heritage or religious background in a Muslim that’s a Muslim extremist – that’s what we need to look for,” he said. “To exclude the FBI from looking in that direction is a mistake. We’ve gone so far in political correctness to stay away from the term ‘profiling’ that we can’t do a regular investigation.”