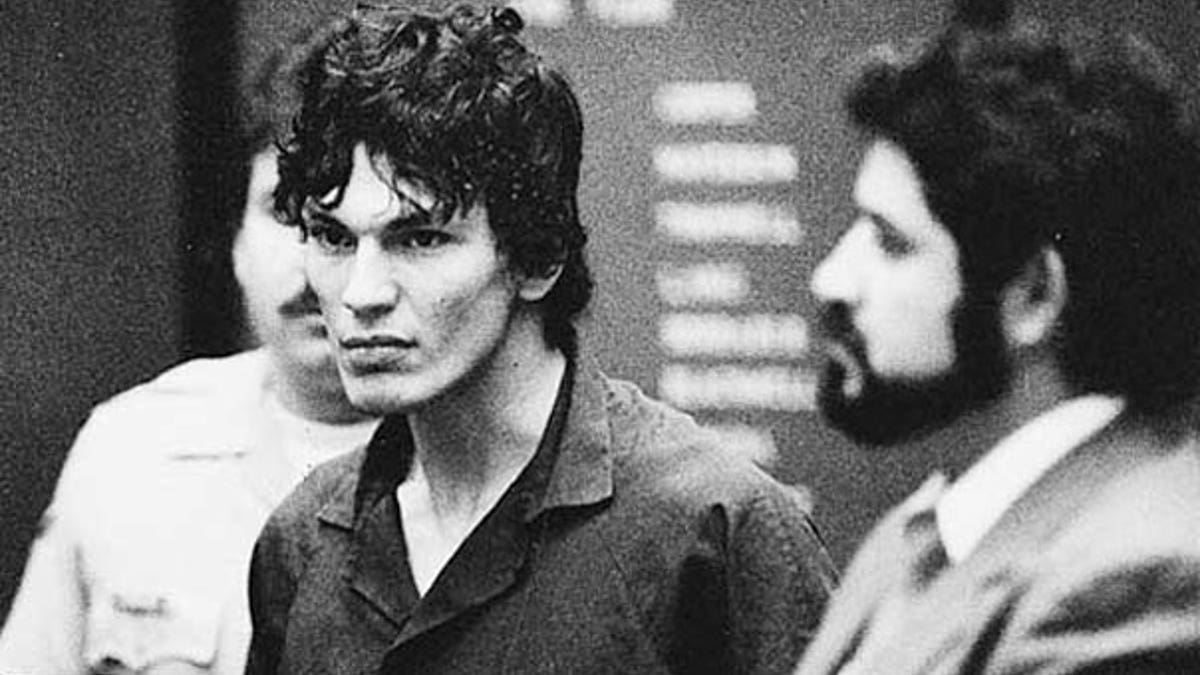

FILE: Serial killer Richard Ramirez was sentenced to death in 1989 for committing a string of gruesome murders, but will likely die of old age rather than face execution because of the lengthy appeals process. (AP)

On June 28, 1984, a young man broke into the home of 79-year-old Jennie Vincow in Los Angeles. Over the course of a few hours he ransacked the elderly woman's apartment, raped her and repeatedly stabbed her. He then slashed her throat so badly that she was nearly decapitated. Her son found her body the next day.

It was the beginning of a spree of murder, rape and burglary that gripped Southern California for 14 months — until Richard Ramirez, a 24-year-old drifter from El Paso, Texas, was arrested in Los Angeles. By then, the man who had come to be known as "the Night Stalker" had killed no fewer than 13 people and brutally raped and disfigured several more, including:

• Vincent and Maxine Zazza. Vincent, 64, was found in his home with a bullet hole in his temple. His wife, Maxine, 44, was found naked in her bed, her eyes gouged out and with stab wounds on her face, neck, breasts, abdomen and groin.

• Elyas Abowath, 35, who was shot in the head while he slept. Ramirez allowed Abowath's wife, 29, to live — after he raped and sodomized her.

• Lela and Max Kneiding, both 66, found shot to death and mutilated with a machete.

Ramirez's crimes were marked by the satanic pentagrams he left on his victims and the sexual abuse of women who were sometimes forced to sing praises of Satan before he raped them.

No one — including Ramirez himself — doubts that his killing spree earned him a cell on California's death row. When he was found guilty of capital murder in 1989, he remarked, "Big deal. Death always went with the territory."

But so far, it hasn't. For the past 21 years, Richard Ramirez has sat in a single cell on death row in San Quentin, and he is still years away from his last meal. According to experts familiar with his case, the ritual killer is "only about halfway through the appeals process" that will end in his execution.

If that process continues at its present pace, Ramirez, who committed most of his crimes when he was in his mid-20s, won't be put to death until he is 71 years old — if he lives that long.

That a man could sit nearly 50 years on death row isn't surprising — especially in California, where critics of the state's system say the odds of a convicted killer actually living long enough to be put to death are about 100 to one. Most prisoners sentenced to execution, studies and experts say, simply die of old age or other illnesses while in prison as the appeals process grinds on.

"The death penalty is purely symbolic in California," says Natasha Minsker, who just completed a study of the death penalty in California for the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California. With almost 700 people on death row in the state, the study found not only that maintaining a prison and legal system to support the death penalty cost the state billions of dollars, but that, for all the money spent, the penalty is rarely used. Since 1977 only 13 people have been executed. During the same period, 59 death row inmates died of old age or other infirmities.

What is most surprising about Ramirez's appeals is that there is nothing extraordinary about them. It is the same process every prisoner on death row goes through. By law, every death sentence in California has to be appealed and reviewed by the state's Supreme Court to ensure that no one who is innocent faces the ultimate penalty.

It is a slow process that begins with a very long delay. According to Minsker and other experts, it generally takes as many as five years after a conviction before a lawyer is even appointed to file a mandatory appeal. "Nothing happens in those five years," she said. The reason, according to the California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice, a panel appointed to look at the state's death penalty system, is that there are just too few experienced lawyers available to handle the growing number of appeals.

Then, it can take years for the appeal to be written and filed. In Ramirez's case, his first appeal didn't reach the California Supreme Court until 2002. In other cases lawyers have filed for and been granted more than 40 delays before even filing appeals. In virtually all death row appeals the cases are handled by public defenders, specially trained in the field, and paid for by taxpayers. And there is no limit to the number of appeals that can be filed.

Then, because of the gravity of the charges and California law, the appeal gets filed directly with the California Supreme Court, which is the ultimate arbiter of all state legal matters and is simply overwhelmed by death row cases. In 2008 it had a backlog of more than 400 capital cases alone, a number that has grown since then.

Death penalty convictions also require that all habeas corpus appeals go directly to the Supreme Court. These appeals concern matters that might not be in the trail record, such as the discovery of new evidence, prosecutorial misconduct, or ineffective legal counsel. In virtually all other criminal cases, these appeals are handled by the courts that try them. Efforts to allow lower courts to pick up some of the load have been proposed over the years, but no action has been taken by the state's legislature.

Among the arguments that Ramirez made in his appeals process, only one seemed to carry weight: his argument that he had ineffective counsel at his trial. He said his two lawyers, who were hired by his parents, had only five years of legal experience between them when they took on the most complicated case in the history of the state's legal system. That appeal was denied in 2005 — and immediately appealed. Calls to Ramirez's attorneys and appellate attorney were not returned.

In September 2006 the California Supreme Court finally turned down that appeal, ending his appeals before the state courts.

But that didn't trigger the required hearing to set an execution date. Instead, it triggered the beginning of a new set of appeals — this time to federal courts, which do not consider these cases until all efforts in state courts have been exhausted, according to an expert with the California Attorney General's office.

And here, according to sources in the attorney general's office, things can take a while and get very complicated. "For example," said a lawyer who asked not to be named, "if the appellant brings up an issue that involves issues about the state's conduct, the federal process stops and the state ... begins again. It can get very complicated."

For Ramirez, the federal process is just beginning, and its length will be determined by the arguments he makes. But experts say he has an edge over death row inmates from other parts of the country, because his federal appeals will be heard in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Unlike other federal appeals courts, which tend to spend little time on death penalty cases, the Ninth Circuit takes them very seriously. In 2005 its chief judge told the Los Angeles Times that "We don't turn them (executions) out the way a lot of Southern states do. We go to such lengths to minimize the possibility of error, and we've built in a lot of delay."

Just how long the federal appeals process will take is impossible to answer, but it will not be quick. An appeal denied by a three-judge appeals panel, the first step, can be appealed "en banc," to the entire nine-judge panel. If that is denied, the next stop is the United States Supreme Court. But again, there is no limit to the number of appeals he can file, and no way to know how long it will take the courts to dispose of them.

Until then, Ramirez will just grow old — older than most of the people he killed back when he was 24.