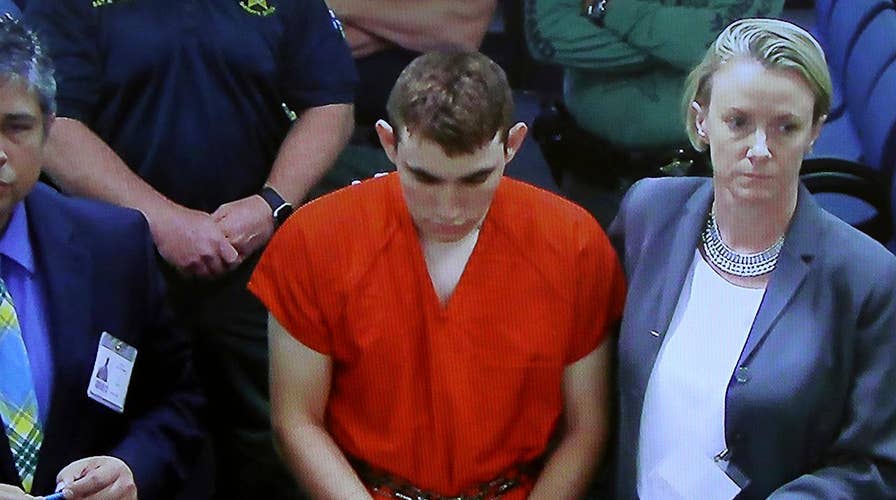

Why so many missed warning signs in the Florida shooting?

Questions emerge over whether officials missed warning signs about Nikolas Cruz; reaction on 'Journal Editorial Report.'

Nikolas Cruz, who methodically went up and down the hallways of his former Florida high school on Valentine’s Day, killing 17 people, had a history of threatening others. Adam Lanza, who killed almost two dozen children in a Connecticut school in 2012, struggled with developmental disorders and was on psychiatric medication, which he had stopped taking. Jiverly Wong was suspected of suffering from paranoia before he walked into the American Civics Association in New York in 2009 and murdered 13 people.

The most recent mass killing in Florida last month has reignited the debate over the extent to which mental illness plays a role in such violence, and even about what is meant by mental illness. The horror at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High also is shining a light on the contradictory views among prominent criminology and mental health experts about mental illness as a risk factor in mass shootings.

In a study of 185 public mass shootings– defined as an incident in which four or more people are killed at a public location – from 1900 through 2017 criminologist Grant Duwe found that 59 percent were committed by people who had been diagnosed as mentally ill or showed signs of having a serious mental disorder before the attack.

“Typically what we see with those who carry out a mass public shooting is that they do suffer from a mental disorder, in some cases it’s diagnosable, or there’s some information from friends and family that indicates they suffered from mental illness,” said Duwe, who is the research director for the Minnesota Department of Corrections and author of “Mass Murder in the United States: A History.”

James Holmes convicted of the murder of 12 people and the attempted murder of 70 others in the 2012 Aurora shooting at a Century movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. (AP/Denver Post)

“Paranoid schizophrenia is what is more common among these individuals,” Duwe told Fox News. “They feel like large groups of people are out to get them, and that they are responsible for making their life miserable. We also see that individuals who do this are loners, they’re not trusting, so they don’t have close friendships of social relationships.”

Mother Jones, the left-leaning publication, compiled a database of mass shootings going back to 1982, and found that about half involved some form of “mental health issue.” They included people who had been diagnosed with serious conditions, but also those who had domestic violence and work conflict histories.

An analysis by Everytown for Gun Safety released last year showed that in mass killings between January 2009 and December 2016, the shooter displayed at least one red flag, or troubling behavior, in 42 percent of cases.

At the same time, many studies on mass shootings and mental illness show a smaller link.

Dylan Roof killed nine people at a Charleston, South Carolina church on June 17, 2015 (AP)

Many widely cited studies, including some conducted by the National Institutes of Health, on gun violence show that anywhere between 4 and 20 percent of the incidents are caused by people with a serious mental illness.

Jeffrey Swanson, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University who specializes in gun violence and mental illness, conducted a study funded in part by the National Institutes of Health that found that 4 percent of gun and other violence is traceable to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression – the three mental health conditions most frequently found in violent incidents.

Swanson says the role of mental illness is overplayed after a shooting that grips at the country.

A mass shooting is so disturbing, so irrational, and horrifying, people want to know why is happened, and mental illness is the perfect master explanation.

“A mass shooting is so disturbing, so irrational, and horrifying, people want to know why it happened, and mental illness is the perfect master explanation,” said Swanson to Fox News.

What is more common among perpetrators of mass shootings, Swanson said, are potentially red flag behaviors such as festering anger, alienation, and bitterness over being bullied, perhaps, that do not meet the threshold of a mental disorder -- and that may not be perceptible even to those close to the person -- but that can lead to violence. Substance abuse is a common thread in mass shootings, found to be a factor in nearly 40 percent of shooters.

“If we were to cure mental illness, all of it, tomorrow, how much of our violence problem would go down? It would go down about 4 percent,” said Swanson, who has studied the issue for the National Institutes of Health. “The mass shooters, with some exception, have been angry, alienated, emotionally troubled young men who act out these incredibly deviant cultural scripts and have access to firearms.”

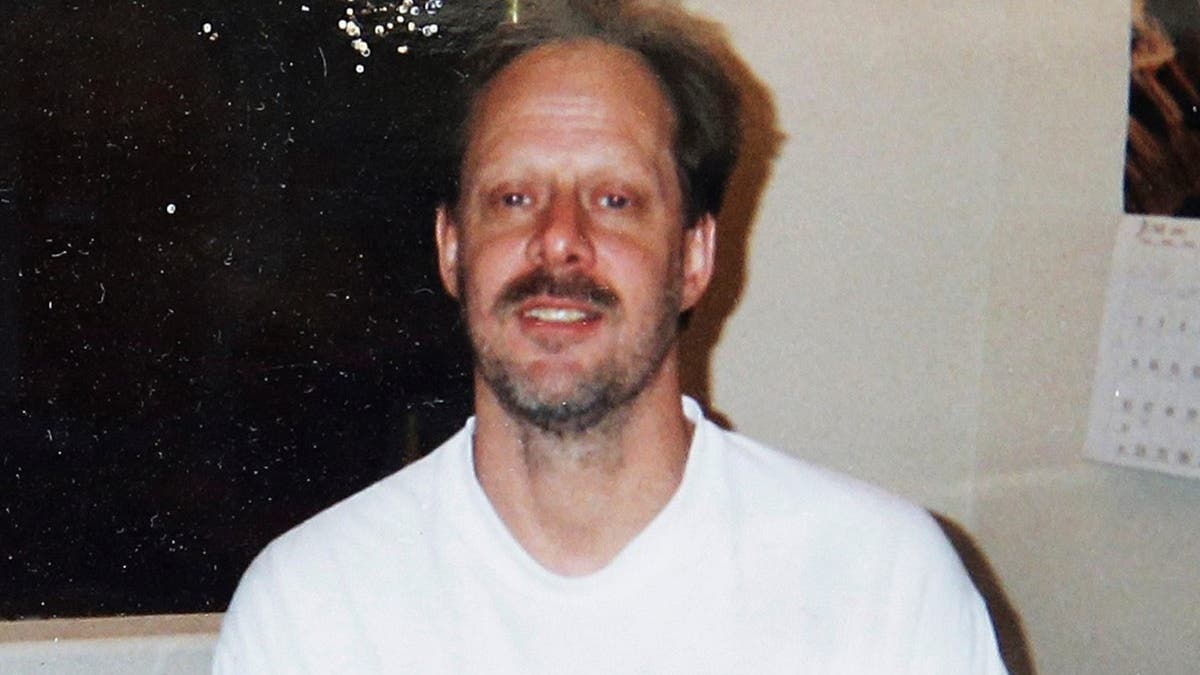

Stephen Paddock opened fire at a Las Vegas music festival, killing 58 people. (AP)

“There are tons of people who are risky, who are angry or suicidal, but who would pass a background check,” Swanson said. “They don’t have a felony conviction, they’ve never been involuntarily committed. How do you make sure dangerous people don’t get access to firearms?”

Duwe argues that the role of mental illness in mass shootings is underplayed.

“Part of the blowback with connecting mental illness to mass shootings is the fear that mentally ill people will be stigmatized,” Duwe said, adding that the concern is a valid one. “That’s what we try to be careful with, most of the people with serious mental illness are not violent.”

“But we should not ignore the connection between mental illness and mass shootings that is very real,” said Duwe, who recently co-authored an op-ed on the issue in The Los Angeles Times. “The issue has become very politicized, like tribal warfare.”

A major obstacle to a better system for predicting who might commit a mass shooting, experts say, is that it is relatively rare, and more funding is needed to study it more in-depth.

Many studies differ in their definition of mental illness, with some looking at diagnosable conditions, others only at serious ones such as paranoid schizophrenia, and still others taking a broad approach, including more common things such as attention deficit disorder and anxiety.

“It’s an elastic boundary, a rubber ruler,” Swanson said. “About 48 million people in the U.S. have some kind of diagnosable mental illness.”

We should not ignore the connection between mental illness and mass shootings that is very real. The issue has become very politicized, like tribal warfare.

What is more, not all studies or news reports look at the same categories of violence when addressing the role of mental illness, Duwe and Swanson noted.

Some look at all violence, others look at mass killings (which may or may not involve guns), and still others look at mass shootings that don’t occur in a public place or that targets strangers – such as when a disgruntled fired employee commits workplace violence or someone kills four or more people in a household or when a criminal kills several people in the course of say a robbery.

“There has not been systematic assessment of mass shooters” that would meet scientific criteria, Swanson said. “We often are operating on the basis of sketchy information” about a perpetrators'odd behavior.

Gun rights advocates say the answer is not curbing Second Amendment rights, but acting more responsibly when behavioral “red flags” are observed, as they were in the case of Cruz in Florida. They argue that the massacre likely would never have happened if law enforcement officials had simply done their job and investigated numerous leads suggesting Cruz had mental illness issues.

One approach gaining momentum is Red Flag Laws, which allow relatives and officials to seek a court order to remove guns from dangerous people. Five states have the laws, and Red Flag measures are pending in roughly 20 others.

In a written statement, the FBI said a person close to Cruz contacted the agency's tip line Jan. 5 to report concerns about "Cruz’s gun ownership, desire to kill people, erratic behavior, and disturbing social media posts, as well as the potential of him conducting a school shooting."

Florida does not have a Red Flag Law.

"Under established protocols, the information provided by the caller should have been assessed as a potential threat to life," the FBI said.

In a speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference on Thursday, the leader of the National Rifle Association Wayne LaPierre said that opponents of gun rights want to "sweep under the carpet" the failure of school safety, families "and even the unbelievable failure of the FBI" to prevent the shootings. LaPierre made the case that there is room for the gun lobby and gun control advocates to find common ground.

Efforts by Fox News to get a comment from the NRA were unsuccessful.

Bonnie Zampino, a behavioral health professional who trains educators, among others, on how to manage people with mental illness and behavioral issues, said it’s important that school officials, counselors, families and law enforcement work together and establish communication lines when a young person begins exhibiting so-called red flag that might lead to violence.

Often, she said, efforts to address such behaviors are disjointed or have no follow-up.

“This young man was exhibiting behaviors that would indicate that he had been exposed to trauma in life, he received medical care, he was evaluated, they didn’t find the need for further care,” said Zampino of Cruz, based on published information.

“It’s our job to be the professional who can look at the behavior, meet the need, stop the aggression,” said Zampino, who has an autistic child. “But [too often] we’re not paying enough attention, we’re not talking to one another.”

“Here we help teachers understand when they see a child coming into their classroom that clearly shows an issue and they’re being aggressive, how to get ahead of that behavior and deal with the trauma and how not to trigger the aggression,” she said. “We teach teachers proactive approaches."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.