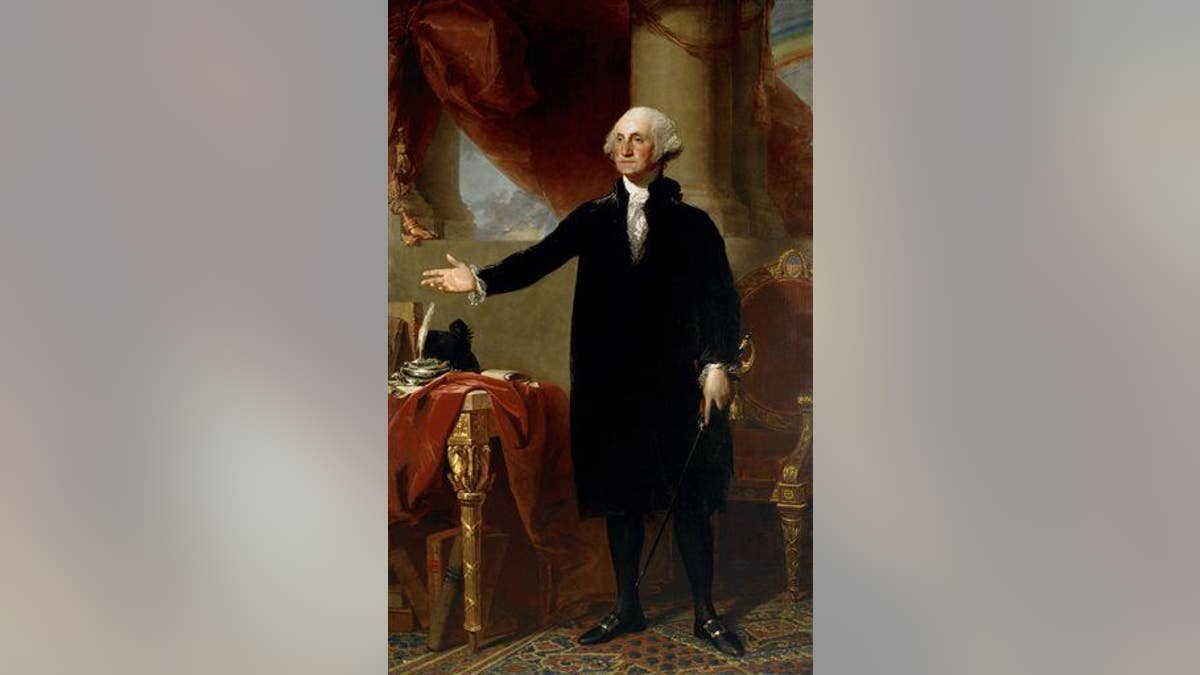

George Washington, America's first president, was impressively difficult to kill. (AP Photo/The National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

On June 25, 1775, William Tryon — the governor of the British colony of New York and a fierce loyalist to the crown — returned to New York City after a yearlong trip overseas. As such, he fully expected to be greeted by a public procession on Broadway.

Tryon disembarked from his boat and was indeed met with a parade, but there was just one problem: It wasn’t for him.

That same day, the new Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, had arrived in the city and was met with a hero’s welcome. Adding insult to injury, Tryon was not only forced to wait several hours for Washington’s procession to end, he also had to put up with a crowd jeering — at him.

GEORGE WASHINGTON'S HEADQUARTERS FLAG MAKES HISTORIC RETURN TO PHILADELPHIA

“Tryon, accustomed to calling the shots in his own colony, must be appalled that this enemy … would parade through Manhattan right under his nose. New York is Tryon’s city, and the public should be cheering for him — not for some usurper,” write Brad Meltzer and Josh Mensch, authors of the new book, “The First Conspiracy: The Secret Plot to Kill George Washington and the Birth of American Counterintelligence” (Flatiron Books), out Jan. 8.

It was at that moment, two months after the start of the American Revolutionary War, that Tryon likely first heard of the army’s formation. He immediately realized that this Washington fellow posed a threat to running his colony his way.

Two months after the start of the American Revolutionary War ... Tryon ... realized that this Washington fellow posed a threat to running his colony his way.

For Washington, Tryon was as dreaded an enemy as he’d find: one who would try to end both his life and the burgeoning new nation, embroiling the commander in chief’s housekeeper, and even his bodyguards, in his plot.

And yet, Manhattan still boasts a 67-acre park — home to The Cloisters and some of the city’s most beautiful green space — named for the man who wanted Washington dead.

And yet, Manhattan still boasts a 67-acre park — home to The Cloisters and some of the city’s most beautiful green space — named for the man who wanted Washington dead.

Tryon was born to an aristocratic family in Norbury Park, England, in 1729. He fought against the French in the Seven Years War before a bullet to his leg in the 1750s ended his military service.

Seeking opportunity in the colonies, he was named governor of North Carolina in 1765. There, he made clear how he would deal with those who defied the crown.

A few years after his appointment, a group of North Carolina farmers organized a revolt against the high fees and taxes they were required to pay to the British. Many of these men couldn’t feed their families, yet the tax was, the authors write, “imposed directly by Governor Tryon, to pay for a vast, lavish palace he was building for himself … This luxurious Governor’s mansion, known everywhere as ‘Tryon’s Palace,’ became a symbol of royal greed and corruption.”

The governor sent a group of mercenaries to meet several hundred of the protesters. “Tryon’s forces overwhelmed the poorly armed farmers, killed or wounded several dozen, and shackled the group’s leaders,” the authors write. “The leaders were quickly tried … for treason.”

CHRISTMAS DAY RE-ENACTMENT OF GEORGE WASHINGTON DELAWARE RIVER NIXED FOR SECOND YEAR IN A ROW

Those declared guilty were to be “hanged by the neck … cut down while yet alive … [their] bowels should be taken out and burned before [their] face … [their] head should be cut off, and [their] body should be divided unto four quarters, which were to be placed at the King’s disposal.”

Such was justice under Gov. Tryon, who was transferred in 1772 to New York, where he curried favor with influential families.

And once Washington entered the scene, Tryon was “determined to strike back at the revolutionaries and reassert his power.”

But by fall, revolutionary fervor continued to grow. City leaders were being tarred and feathered by angry mobs, or chased out of town altogether.

Tryon was determined to reclaim his city. “If political solutions fail, then other means are necessary,” the authors write.