Coast Guard to end search for missing Florida teens

Boys' relatives say they plan to keep looking privately

OPA-LOCKA, Fla. – After hundreds of rescue workers fanned out across a massive swath of the Atlantic for a full week, the Coast Guard's search for two teenage fishermen ended Friday, a heart-rending decision for families so convinced the boys could be alive they're pressing on with their own hunt.

The agency said it ended the search at sunset, as it had announced earlier in the day. The Coast Guard searched waters from South Florida up through South Carolina without success.

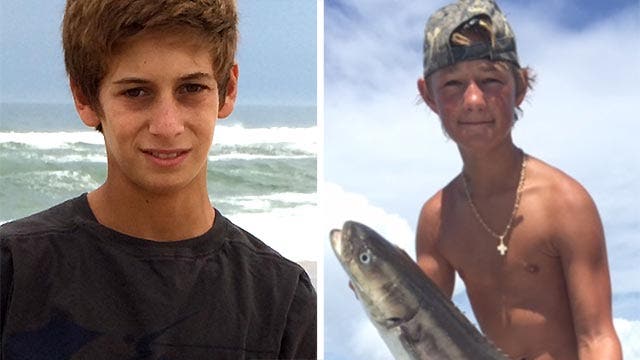

Even as officials announced at noon that the formal search-and-rescue effort would end at sundown, private planes and boats were preparing to keep scouring the water hoping for clues on what happened to the 14-year-old neighbors, Perry Cohen and Austin Stephanos.

Capt. Mark Fedor called the decision to suspend the search "excruciating and gut-wrenching." He suggested what long had been feared by observers — that the boys had surpassed any reasonable period of survivability — with his offering of "heartfelt condolences."

"I know no statistics will ease the pain," he said in recounting the seven-day, nearly 50,000-square-nautical-mile search. "We were desperate to find Austin and Perry."

With volunteers ready to keep searching all along the coastline and about $340,000 in search-fund donations by Friday evening, the families promised to keep looking for their sons.

Nick Korniloff, the stepfather of Perry, addressed a horde of media outside his home on a quiet street in Tequesta, Florida, saying air searches led by private pilots would go on alongside new efforts led by former members of the military and others with special training.

"We know there's a window here and we think there's an opportunity," he said, "and we will do everything we can to bring these boys home."

Those who have met with the families believe the private search could go on at least for weeks.

"How could you go back to normal?" said Tequesta Police Chief Christopher Elg, who has stayed in regular contact with the families. "They may very well devote a large portion of the next few weeks, months, maybe even years just toward hope and doing what they can to bring themselves a sense of peace."

The Coast Guard had dispatched crews night and day to scan the Atlantic for signs of the boys. They chased repeated reports of objects sighted in the water, and at times had the help of the Navy and other local agencies. But after the boys' boat was found overturned Sunday, no useful clues turned up.

The families had held out hope that items believed to have been on the boat, including a large cooler, might be spotted, or that the teens might even have clung to something buoyant in their struggle to stay alive. Even as hope dimmed, experts on survival said finding the teens alive was still possible. The Coast Guard said it would keep on searching until officials no longer thought the boys could be rescued.

The saga began July 24, when the boys took Austin's 19-foot boat on what their families said was expected to be a fishing trip within the nearby Loxahatchee River and Intracoastal Waterway, where they were allowed to cruise without supervision. The boys fueled up at a local marina around 1:30 p.m. and set off, and later calls to Austin's cellphone went unanswered. When a line of summer storms moved through and the boys still couldn't be reached, police were called and the Coast Guard search began.

The boys grew up on the water, constantly boated and fished, worked at a tackle shop together and immersed themselves in life on the ocean. Their families said they could swim before they could walk. They clung to faith in their boys' knowledge of the sea, even speculating they might have fashioned a raft and spear to keep them afloat and fed while adrift.

"It is a mother's prayer that you will be safe and sound in our arms today," Austin's mother, Pamela Cohen, tweeted Friday. "Missing you both more than you could ever imagine."

Many unknowns about the boys' status persisted throughout the ordeal, including whether they were wearing life jackets and whether they had food or water. The Coast Guard said it tried to err toward optimism in deciding how long to press on.

Along the way, some suggested the teens shouldn't have been allowed to boat on their own. Many others, though, voiced support, saying voyages with set boundaries are normal among boating families, and that the parents had no control over what ultimately happened.

Locals turned out night after night for vigils, poured money into the private search fund, used their own boats and planes and walked the coastline in pursuit of any little clue that might make a break. The efforts got an early boost from a high-profile neighbor of the families, NFL Hall of Famer Joe Namath, who helped garner publicity for the story.

___