'Good Cemeterian' honors veterans by restoring gravestones

Every week, Andrew Lumish makes it his mission to find, clean and restore veteran's monuments long forgotten. He takes before and after photos of his work and posts them to his Facebook page and website, titled with his nickname 'The Good Cemeterian,' along with a short biography of the person behind the name as a tribute to their life.

TAMPA, Fla. – On any given day, Andrew Lumish arrives at a historic Tampa-area cemetery without fanfare or attention. He’s there to carefully restore veteran’s gravestones blackened by the elements and decades of neglect.

Cemeteries across the country will show you a similar scene—thousands of long-forgotten monuments belonging to those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

But Lumish, a cleaning company owner, aims to refurbish the memories – and the gravestones – of America’s heroes whose time-worn tombstones have started falling apart.

Lumish said he stumbled upon a Tampa cemetery five years ago to photograph some gravestones, but what he saw that day would change his life.

“So many veteran’s monuments…were in really poor condition and it was upsetting to me,” he said. “I didn’t want for them to be forgotten…I started to research how to properly restore monuments.”

His preparation is always the same, even after 1,500 completed restorations.

He is given permission to restore a monument from cemetery staff or a descendant, charges no fee for his services and brings all his own equipment—a few 5-gallon water containers, some microfiber towels and an assortment of over 12 brushes ranging in shape and size.

Recent, he was restoring the gravestone of Milton H. Phelps, a U.S. Army Private First Class in World War II who died in 1973 at the age of 67.

“Each one tells a story…our subject right here is originally from New York state,” says Lumish, as he methodically sprays the stone while scrubbing away mold and mildew so deeply permeated that each swirl of his brush creates a wave of green muck.

He rinses the stone with water to check his progress and sprays it again with something called D/2 biological solution, which Lumish said is the only product used to clean monuments in national cemeteries.

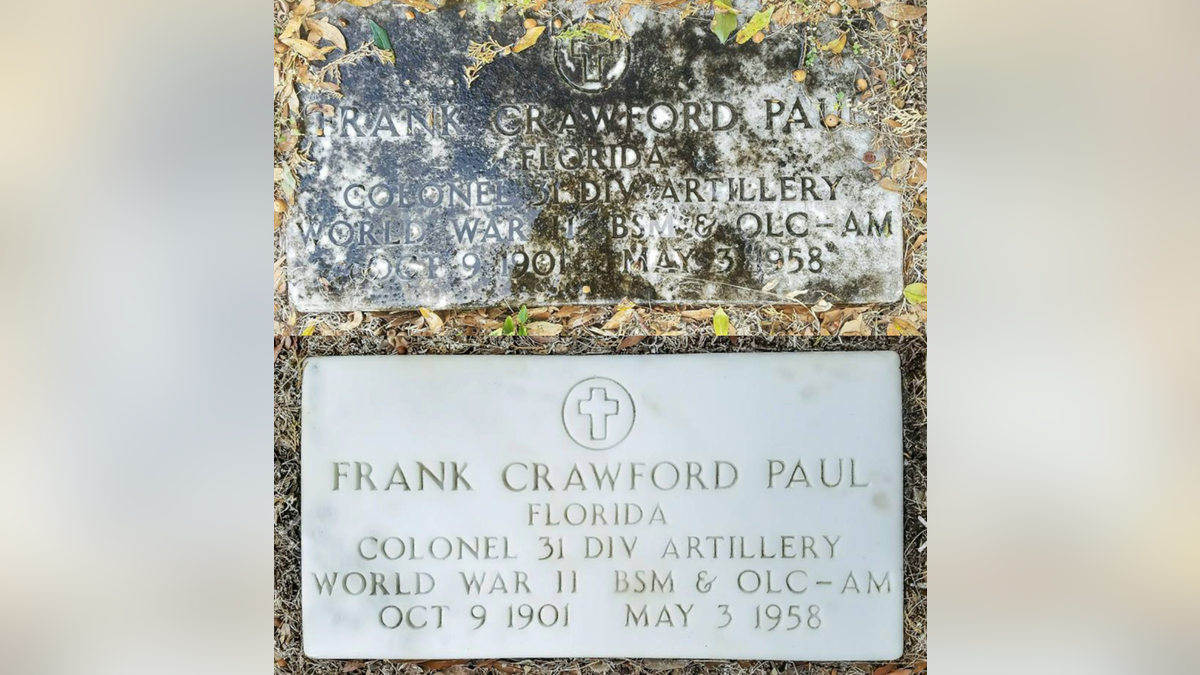

Lumish's restoration work transforms veteran’s gravestones blackened by the elements and decades of neglect into pristine slabs of marble and granite. (Facebook - The Good Cemeterian)

Lumish said in a typical eight-hour day, he can complete the first cleaning phase of four to five monuments.

“A monument restoration has to be done by hand, you cannot use a pressure washer…so a monument will take minimally two months to restore and some take in excess of a year,” he said. “I won’t reveal a restoration until it’s reached its pinnacle and peak and it’s ready to be shown.”

This is the first of many visits he will make to Phelps’ burial site over the coming months, and each time, he will learn more about each veteran’s personal story.

“It’s very important to me,” he said. “It’s become a mission of sorts.”

Joe Caltagirone, caretaker of the L'Unione Italiana cemetery, where Lumish has completed several restorations, said his work means a lot to the families of the deceased veterans.

“He is treating the individual veterans as if they were members of his family,” Caltagirone said. “Words can’t express how much we appreciate that.”

Lumish’s mission doesn’t end once the gravestones are clean. He takes before-and-after photos and posts them to his Facebook page and website, titled with his nickname "The Good Cemeterian," along with a short biography so his thousands of followers can celebrate their life.

“You find these things that are unbeknownst to anyone when you walk by or drive by a stone in a cemetery…it represents a life that we should respect and remember because we learn so much,” Lumish said.

He and his assistant, Jen Armbruster, use numerous genealogical websites and old newspaper articles to tell the story of the person behind the name.

"I never anticipated that these restorations from 100 or longer years ago would personally affect people in today’s times the way that they do," Lumish said. (Fox News)

“The individuals that we honor didn’t consider themselves heroes, they didn’t toot their own horn or pat themselves on the back—we’re doing it now…we don’t only talk about their service, we talk about their lives, from the day they were born until their last day on earth,” he said. “We are delving into that person’s life so that we can respectfully tell what that person went through…I don’t want anyone to be forgotten.”

One of those Lumish wants everyone to remember is his friend, 12-year U.S. Air Force veteran Chris Scala, who took his own life in 2013 after battling post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

"We honor the past, but I also always honor him,” he said. “I always think of him."

Lumish’s dedication to Scala and others is getting nationwide attention—hundreds of new "Good Cemeterians" across the country are joining his cause. He plans on providing them with starter cleaning kits to use in their own local cemeteries.

Inspired by the outpouring of support for his work, he created “The Good Cemeterian Historial Preservation Project,” a non-profit raising money for gold star families and veterans suffering from PTSD.

At the Veterans of Foreign Wars’ national convention in Kansas City, Mo. later this month, Lumish will be honored with a National Citizenship Award.

“Personally, I’ve learned a lot through these restorations and telling these stories…I learn every single day and unless you’re learning every single day, you’re not living,” he said. “So, I’m going to live this life, however long it’s going to be, and leave it a better place than I came into it. That’s my goal.”