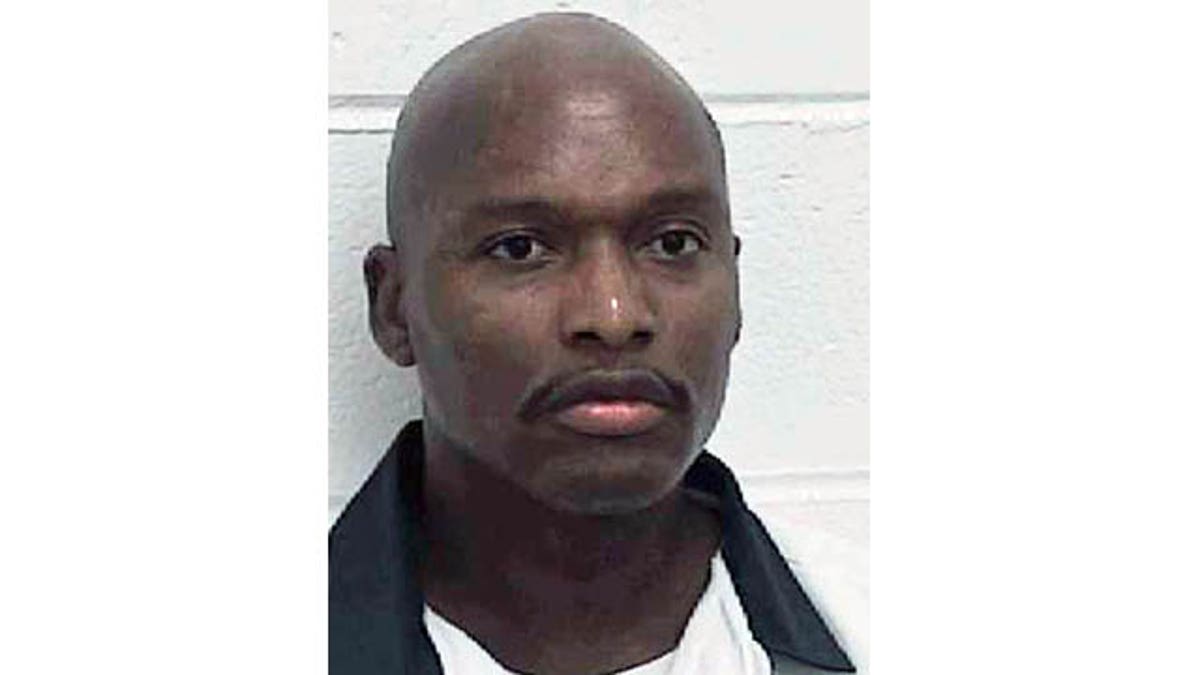

FILE - This undated provided by the Georgia Department of Corrections shows convicted murderer Warren Lee Hill. (AP Photo)

ATLANTA – The state that was the first to pass a law prohibiting the execution of mentally disabled death row inmates is revisiting a requirement for defendants to prove the disability beyond a reasonable doubt -- the strictest burden of proof in the nation.

A state House committee is holding an out-of-session meeting Thursday to seek input from the public. Other states that impose the death penalty have a lower threshold for proving mental disability, and some don't set standards at all.

Just because lawmakers are holding a meeting does not mean changes to the law will be proposed, and the review absolutely is not a first step toward abolishing Georgia's death penalty, said State Rep. Rich Golick, R-Smyrna, chairman of the House Judiciary Non-Civil Committee.

Georgia's law is the strictest in the U.S. even though the state was also the first, in 1988, to pass a law prohibiting the execution of mentally disabled death row inmates. The U.S. Supreme Court followed suit in 2002, ruling the execution of mentally disabled offenders is unconstitutional.

The Georgia law's toughest-in-the-nation status compels lawmakers to review it, Golick said.

"When you're an outlier, you really ought not to stick your head in the sand," he said. "You need to go ahead and take a good, hard look at what you're doing, why you're doing it, weigh the pros and cons of a change and act accordingly or not."

Thursday's meeting comes against the backdrop of the case of Warren Lee Hill, who was sentenced to die for the 1990 beating death of fellow inmate Joseph Handspike, who was bludgeoned with a nail-studded board as he slept. At the time, Hill was already serving a life sentence for the 1986 slaying of his girlfriend, Myra Wright, who was shot 11 times.

Hill's lawyers have long maintained he is mentally disabled and therefore shouldn't be executed. The state has consistently argued that his lawyers have failed to prove his mental disability beyond a reasonable doubt.

Hill has come within hours of execution on several occasions, most recently in July. Each time, a court has stepped in at the last minute and granted a delay based on challenges raised by his lawyers. Only one of those challenges was related to his mental abilities, and it was later dismissed.

A coalition of groups that advocate for people with developmental disabilities pushed for the upcoming legislative committee meeting and has been working to get Georgia's standard of proof changed to a preponderance of the evidence rather than proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Hill's case has drawn national attention and has shone a spotlight on Georgia's tough standard, they say.

The process has taken an enormous amount of education, said Kathy Keeley, executive director of All About Developmental Disabilities. Rather than opposition to or support for the measure she's pushing, she's mostly encountered a lack of awareness about what the state's law says, she said.

The groups are hoping to not only express their views at the meeting, but also to hear from others to get a broader perspective, Keeley said. The changes should be relatively simple and very narrow in scope, targeting only the burden of proof for death penalty defendants, she said.

Ashley Wright, district attorney for the Augusta district and president of the state District Attorneys' Association, said prosecutors question the logic of changing a law that they don't see as problematic and that has repeatedly been upheld by state and federal courts.

"The district attorneys don't believe that you change a law for no reason and, in this case, the law appears to be working," she said. "Where has a jury done a disservice? Why are we putting all our eggs in the defendant's basket and forgetting that there's a victim?"

Prosecutors agree that the mentally disabled shouldn't be executed, and defendants are frequently spared the death penalty when there is proof of their mental disability supported by appropriate documentation from credible and reliable experts, she said.

But Hill's lawyer, Brian Kammer, argues that psychiatric diagnoses are complex, and "experts who have to make diagnoses do not do so beyond a reasonable doubt, they do it to a reasonable scientific certainty."

Furthermore, he said, disagreements between experts make the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard nearly impossible to meet.

"Even where evidence is otherwise seemingly overwhelming that a person has mental retardation, one dissenting opinion that splits a hair on one or more pieces of evidence can result in that person who's almost certainly mentally retarded being executed," Kammer said.

In Hill's case, a state court judge concluded the defendant was probably mentally disabled. In any other state, that would have spared him the death penalty, Kammer said.

Additionally, three state experts who testified in 2000 that Hill was not mentally disabled submitted sworn statements in February saying they had been rushed in their evaluation at the time. After further review and based on scientific developments since then, they now believe Hill is mentally disabled, they said.

The state has dismissed the doctors' new testimony, saying it isn't credible. And courts have ruled that Hill is procedurally barred from having a new hearing. His lawyers had asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case based on the new evidence, but the high court this month declined to take it up. Hill has a challenge on different grounds pending before the Georgia Supreme Court. But he has exhausted his challenges on the mental disability issue, Kammer said.

Even if changes are made to Georgia's law, they will likely not be retroactive and wouldn't apply to Hill, Keeley said.