Will Nidal Hasan ultimately be given the death sentence?

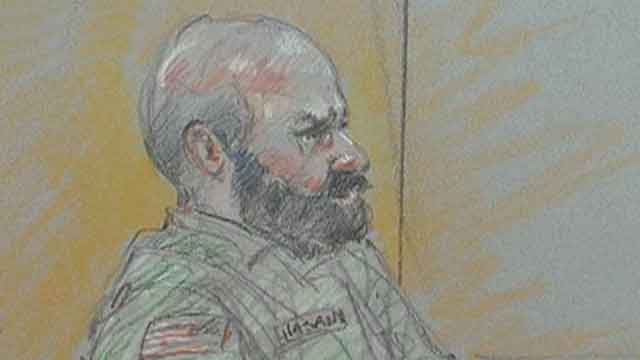

Suspect says 'I am the shooter' massacre at Fort Hood court-martial

The trial of the Fort Hood gunman, who is acting as his own attorney, took a surreal turn as the former Army psychiatrist accused of killing 13 in the November 2009 attack grilled witnesses -- including his former boss in the military and a fellow Muslim who spoke to him the day of the shooting.

After a short opening statement in which ex-Army Maj. Nidal Hasan called himself a "mujahedeen," admitted to the rampage and said "the dead bodies will show that war is an ugly thing," Hasan cross-examined prosecution witnesses, including retired Lt. Col Ben Kirk Phillips, his former boss. When pressed by the defendant, Phillips acknowledged that his officer evaluation report had graded Hasan as "outstanding."

But he declined to cross-examine one of his shooting victims, Sgt. Alonzo Lunsford, who provided the day’s most damning testimony.

Lunsford – who was shot seven times during the incident – described what happened that day, saying he first saw Hasan sitting in a chair, with his arms on his knees while looking at the floor.

He said Hasan then jumped up and ordered the one civilian in the room to leave before shouting, “Allahu akbar” and opening fire. Panic set in among the soldiers, who crowded toward a rear door, which was jammed.

Lunsford said he sprinted for the door at one point while Hasan was shooting, then turned around to see the gunman’s laser sight pointing at him before being shot in the head. Lunsford testified he tried to appear dead, then later decided to flee because, "dead men don't sweat."

He then made another sprint for the door as he was shot six more times before being pulled to safety.

Earlier, Hasan cross-examined Pat Sonti, who met Hasan at the Killeen Islamic Center in Fort Hood the morning of the shooting. Sonti said Hasan took the microphone at the mosque and called for prayer.

“After call to prayer, he bid goodbye and told the congregation he was going home," Sonti said. "I found that odd.”

Hasan asked Sonti to describe the difference between the call for prayer and actual prayer, then asked who is supposed to lead the call.

"Whoever the imam looks at," replied Sonti. "But you know that, sir."

It was not clear how the 42-year-old Hasan plans to fashion his stance into a defense. Hasan had wanted to argue that he shot U.S. troops to protect Taliban fighters in Afghanistan, but the judge forbade the American-born Muslim and former Army psychiatrist from using that defense. Three witnesses took the stand after opening arguments, including the manager of the store Guns Galore, where Hasan had purchased the FN 27 model 5.7 handgun used in the attack.

"Almost every trip I can remember was always [for] ammunition and magazines, extensions and at one point an additional laser,” David Cheadle testified.

Another store employee, Frederick Brannan, who sold the weapon to Hasan, said he saw the shooter in the store almost every week where he would buy up to 300 rounds of ammo each time.

"The sheer quantity of ammo being shot was expensive," Brannan said on the stand adding that he purchased magazine extensions and and a green laser sight that cost $350.

Henricks told the military jury Hasan picked the date of the attack for a specific reason, though he did not immediately reveal details.

The trial is expected to take weeks and possibly months. Taking the witness stand will be many of the more than 30 people who were wounded, plus dozens of others who were inside the post's Soldier Readiness Processing Center, where some service members were preparing to deploy to Afghanistan.

Hasan has never denied carrying out the attack, and the facts of the case are mostly settled. But questions abound about how the trial will play out. How will Hasan question his victims? How will victims respond? How will his health hold up?

The defendant, who was shot in the back by officers responding to the attack, is now paralyzed from the waist down and must use a wheelchair. He requires 15- to 20-minute stretching breaks about every four hours, and he has to lift himself off his wheelchair for about a minute every half hour to avoid developing sores.

The judge, Col. Tara Osborn, told jurors to prepare for a trial that could last several months.

On Tuesday, guards stood watch with long assault rifles outside the courthouse. A long row of shipping freight containers, stacked three high, created a fence around the building, which was almost entirely hidden by 15-foot-tall stacks of heavy, shock-absorbing barriers that extend to the roofline.

The government has said that Hasan, a U.S.-born Muslim, had sent more than a dozen emails starting in December 2008 to Anwar al-Awlaki, a radical U.S.-born Islamic cleric killed by a drone strike in Yemen in 2011.

Authorities in the military justice system have also struggled to avoid reversed sentences on appeal. Eleven of the 16 death sentences handed down by military juries in the last 30 years have been overturned, according to an academic study and court records.

That's one reason why prosecutors and the military judge have been careful leading up to trial, said Geoffrey Corn, a professor at the South Texas College of Law and a former military lawyer. "The public looks and says, `This is an obviously guilty defendant. What's so hard about this?"' Corn said. "What seems so simple is, in fact, relatively complicated."

Fox News Channel's Jennifer Girdon and The Associated Press contributed to this report