Whatever happened to the Flint water crisis?

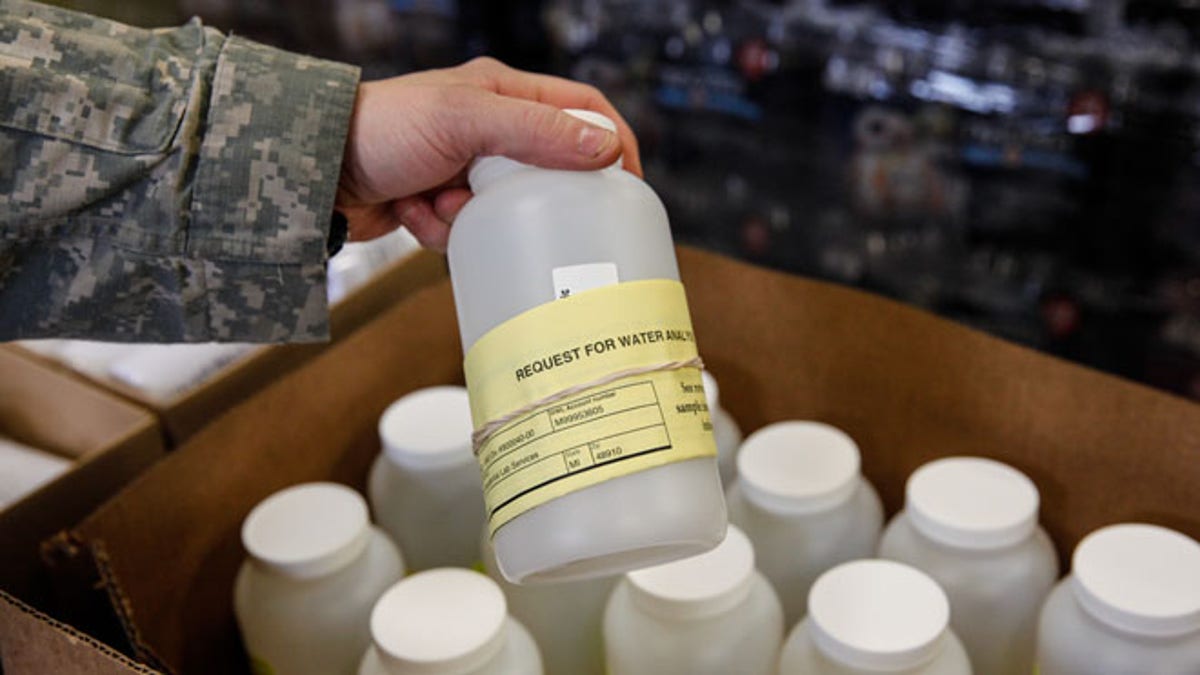

Crews are at work, but less than 25 percent of the lead pipes have been replaced and poisonous water continues to flow into most houses; Mike Tobin investigates for 'Special Report.'

Justice McDonald, 8, keeps a bottle of water nearby so he can clean up and brush his teeth every morning.

He and his 4-year-old brother, Josiah, have learned not to turn on the tap because the water coming out of the faucet is likely poisonous.

This is the way they’ve been living for the past three years, ever since their parents learned that the water in their hometown of Flint, Michigan wasn’t safe.

“We have no other option,” said their mother, Jeneyah Bell McDonald. “I'm definitely not going to take the chance on my children's health and safety.”

FLINT WATER CRISIS CAUSED INCREASE IN FETAL DEATHS, LOWER FERTILITY RATES, STUDY CLAIMS

It was early in 2014 when Flint leaders, under emergency management due to bankruptcy, announced that to save money they were going to switch the source of water from Lake Huron, something they’d been getting through Detroit for the last 40 years, to a local source, the Flint River.

Justice McDonald, 8, keeps a bottle of water nearby so he could clean up and brush his teeth every morning. (Fox News)

It was meant to be a temporary switch to save the city $5 million.

But it was a tragic decision that led to serious consequences.

“Anyone who has lived here for any length of time was shocked because we knew that river was filthy. All kinds of stuff had been dumped in it, for years,” Bell McDonald said.

Days after the switch to the river was made, Bell McDonald could tell something wasn’t right.

“The water coming out of the faucet was brownish colored and smelled very bad,” she said. “There was no way we were going to drink it. We started buying bottled water”.

She said she was still showering in the tainted water, until her hair started falling out.

It was early in 2014 when Flint leaders, under emergency management due to bankruptcy, announced that to save money they were going to switch the source of water from Lake Huron, something they’d been getting through Detroit for the last 40 years, to a local source, the Flint River. That turned out to be a fatal mistake.

Many others in the city of nearly 100,000 claimed to suffer skin rashes, shortness of breath and other health problems they associated with the water.

Doctors sounded the alarm when lead was detected in children.

It turns out the river water had high levels of bacteria and was corrosive. It broke down the lining of old household pipes, which caused lead to seep into the water.

A chemical called orthophosphate could’ve been added to the water to prevent the corrosion to the pipes. But it wasn’t.

“You had a staff at the water treatment plant which was fairly inexperienced,” said Brig. Gen. Michael McDaniel, who was enlisted to manage Flint’s pipe replacement project.

He said the water treatment plant had been there for 50 years.

“They had not used it regularly (because) they were buying water from the Detroit Water Authority,” McDaniel said. “They didn’t have the science down yet.”

MICHIGAN OFFICIAL CHARGED IN DEADLY FLINT WATER CRISIS HEADS BACK TO COURT

Many in Flint wonder if the fact that they live in one of the poorest cities in the nation is a reason why the process is moving so slowly, especially when they see all the recovery efforts carried out in places like Florida and Texas after hurricanes hit. (Getty Images)

In addition to lead exposure, there were dozens of cases of Legionnaire’s disease. Twelve people died. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is trying to determine if the water was the absolute source for the disease.

Now, 15 state and city leaders are facing criminal charges in connection to decisions made that led to the water crisis. Five are facing involuntary manslaughter charges. Trials are scheduled to begin in 2018.

Class-action lawsuits have also been filed on behalf of residents who suffered from the water crisis.

Flint is no longer getting its water from the river. But the water it is getting, although deemed safe at the source, still has to pass through corroded lead or galvanized pipes in many people’s home that can make the water toxic.

So the focus has turned to replacing those pipes, but it’s a massive undertaking. An estimated 20,000 pipes need to be replaced.

McDaniel said that just identifying which pipes need to be replaced and where they’re located has been a nightmare process because city records are written in pencil on index cards. Some cards dating back more than 50 years are no longer accurate.

Efforts are underway now to digitize all the records but it’s another factor slowing the process. Less than a third of the pipework has been completed so far.

Isaiah Oliver, who heads the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, estimates it could cost a half billion dollars to replace all the pipes in Flint.

Millions in federal and state dollars have been allocated for the crisis but after three years, Oliver said, “the one thing we don’t have a lot of is time.”

“I don't think anyone who's living through this crisis is comfortable with the speed at which we're moving from crisis to recovery,” he said.

Flint is no longer getting its water from the river. But the water it is getting, although deemed safe at the source, still has to pass through corroded lead or galvanized pipes in many people’s home that can make the water toxic.

Many in Flint wonder if the fact that they live in one of the poorest cities in the nation is a reason why the process is moving so slowly, especially when they see all the recovery efforts carried out in places like Florida and Texas after hurricanes hit.

“I think the reality is that we don't have systems in place to protect against man-made disasters and that’s what we need to fight for,” Oliver said.

Some say the crisis in Flint could serve as a warning to many other communities facing similar issues – showing that Flint could just be the tip of the iceberg.

“There’s at least, I would guess, 2,000 other municipalities in the United States that have a similar problem, that have lead or galvanized pipes in the ground that they need to replace,” McDaniel said.

There are studies being done on the effects of the tainted Flint water on the people who used it, but definitive results might not come for years.

Josiah McDonald, who was just a baby when the water crisis began, has been diagnosed with autism. Justice has a severe case of eczema. Their parents don’t know for certain but suspect the water is to blame.

And the McDonalds still get a bill of $160 a month for water they can’t use.

At some point, local leaders promise, the water in Flint will be safe to drink again. But convincing residents to believe them will be their biggest challenge.

“Why would we trust them?” Bell McDonald said. “They told us it was safe before but it wasn’t.”