Whatever happened to Detroit filing for bankruptcy?

The Motor City still has an estimated $11 billion in debt, but is in the midst of a notable comeback; Matt Finn takes a closer look for 'Special Report.'

In the shadow of a towering Christmas tree that rivals the Rockefeller Center version in New York City, William Devors smiled as he watched his young daughters loop around the outdoor skating rink near dusk in downtown Detroit.

He says it’s something he’s never done before.

“There was nothing here and we didn’t feel safe,” Devors said. “But so much has changed.”

Devors took the girls for a night out for dinner, skating and shopping at the outdoor Christmas market. The surrounding streets and sidewalks are bustling with workers leaving office buildings and families making a special trip to the festive center city.

Edwin Olsen, who came to see the giant tree and Christmas market, was nearby. “I haven’t been in downtown Detroit in 30 years. ... It was scary. … Now it’s totally different,” Olsen said. “It’s clean, people are friendly.”

The change Devors and Olsen refer to in Michigan’s largest city is dramatic, especially to anyone who lived through the city’s dire and seemingly hopeless years in the 1990s and 2000s.

“We entered a period of chaos,” explained a Wayne State University professor, Robin Boyle. “There was very little leadership, the economy was not working, the real estate market was dead, the jobs evaporated. … The city was facing a really difficult period.”

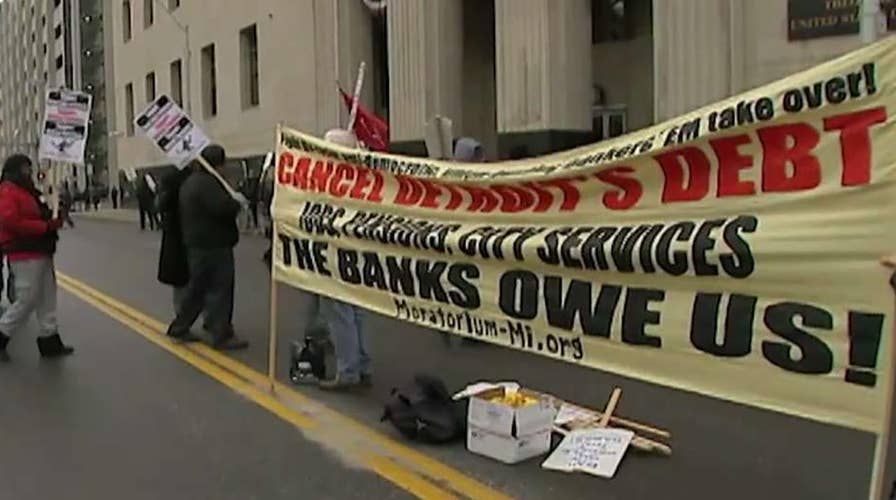

All of the city’s struggles and turmoil came to a head in 2013 when Detroit filed the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. At the time, the city was $18 billion in debt and simply couldn’t pay its bills.

“The city of Detroit, from about the mid-1980s to the bankruptcy period, was an economy that was failing, unemployment was high, poverty was through the roof” Boyle added.

Much of Detroit’s economic turmoil was attributed to several key factors, including years of corrupt leadership, plummeting property values, unsustainable pension deals and a 90 percent drop in manufacturing jobs.

Then the auto industry -- the city’s economic lifeblood -- nearly went under.

The unfortunate joke at that time was that when the automakers sneezed, Detroit caught a cold. Indeed, the city "was dreadfully dependent on the auto industry. Everything is connected to it” Boyle said.

When the jobs left, so did the residents. Detroit’s population went into a steep decline. Fewer residents and businesses meant fewer tax dollars coming in. It got so bad that street lights went out.

There was no money in the budget for things like cutting grass in city parks or fixing broken street lights. Residents complained that when they called 911, it often was at least half an hour before anyone arrived to help.

“For decades it just seemed like everything was taken away from us,” Mayor Mike Duggan told Fox News. “Businesses moved out, auto plants moved out, gas stations and movie theaters moved out and people moved out.”

The decision to file bankruptcy decision changed a lot of that.

“We knew that there was Detroit fatigue all across the country,” said Detroit Regional Chamber President Sandy Baruah. “What bankruptcy allowed us to do is send the message that we're finally taking care of our problems in a very serious way and it worked.”

The bankruptcy filing resulted in Detroit eliminating about a third of its debt. Interest payments were lowered so extra money became available for the city’s budget.

With the added cash, “another one hundred public buses were put on the road so people could actually get around town” said Duggan, who grew up in the area and took the reins of the city just after the bankruptcy was finalized.

“Grass was cut in 275 parks that had closed.” And most important, Duggan said, police and ambulance response time was cut in half.

“The lights came back on in Detroit, literally and figuratively,” Boyle said.

New business came to town, including Quicken Loans, which moved its headquarters into the city, then purchased about 100 buildings and began hiring.

An estimated 25,000 new jobs were created in the city. Restaurants and bars opened and new shopping areas sprang up.

Now Detroit is happily bursting at the seams, Baruah added. “If you're looking for commercial grade real estate … you can't get it. We're essentially sold out. If you want to live in downtown Detroit …or midtown, or if you want to have office space there, essentially you cannot do it right now because everything is booked up.”

“This is emotionally very powerful, to see crowds on the streets shopping on the weekends, to see the nightlife again, to see people moving back into the city. It’s very exciting.” Duggan said.

Wayne State professor Bill Volz agreed, adding that after being a bystander for almost 50 years, “Detroit can now be a participant in the economic upswing of this country.”

Travel book publisher “Lonely Planet” even named Detroit one of the top cities to visit in 2018.

Still, it’s not all nirvana for the place known as “Motown.”

Since all the new development has happened in just the seven-square-mile area of downtown, for the most part, outer residential neighborhoods that make up more than 100 square miles outside the city center are still waiting to see some improvement. Some of those neighborhoods are replete with abandoned, dilapidated homes that neighbors claim are inhibiting development.

The Duggan administration is working on it. More than 4,000 abandoned homes in need of repairs and 8,000 side lots so far have been sold for minimal cost to those willing to fix up and maintain them.

The future of Detroit is bright, assures Duggan. “In the coming weeks you're going to see the skyline change with nearly $2 billion of new high rise buildings that are going to start because we have so many people moving back.”

In fact, it’s expected that the next national census will actually show the population is increasing in Detroit. People are moving in.

“Nobody has said we've solved all our problems,” Duggan said. "But expectations are rising on the part of our residents and it’s our responsibility to meet them, but there is definitely a feeling of optimism in this town.”