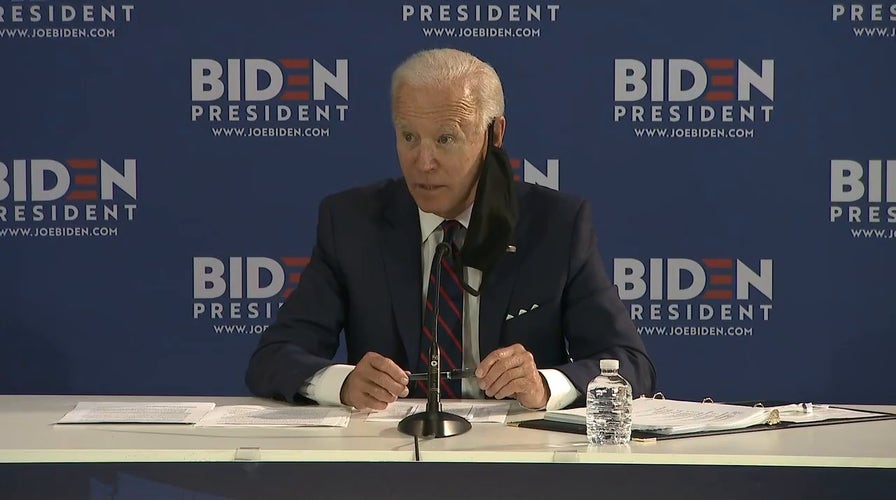

Biden calls out Trump's lack of leadership over coronavirus response

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden on safety guidance given to reopening businesses by the White House.

The coronavirus pandemic has posed a threat that is flying almost completely under the radar.

While nursing and veteran homes have come under scrutiny, little attention has been paid to facilities for the developmentally and intellectually disabled that experts have estimated house more than 275,000 people with conditions such as Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and autism. Many residents have severe underlying medical issues that leave them vulnerable to the coronavirus.

At least 5,800 residents in such facilities nationwide have already contracted COVID-19, and more than 680 have died, The Associated Press found in a survey of every state.

The true number is almost certainly much higher because about a dozen states did not respond or disclose comprehensive information, including two of the biggest states: California and Texas.

Many of these places have been at risk for infectious diseases for years, The AP found.

This 2014 photo provided by the family shows Joe Sullivan of the Chicago-area. (Family photo via AP)

CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

Perhaps the best-known government-funded homes for the disabled are called Intermediate Care Facilities, which range from large state-run institutions to homes for a handful of people. Before the coronavirus hit, regulators concluded that about 40 percent of these facilities -- at least 2,300 -- had failed to meet safety standards for preventing and controlling the spread of infections and communicable diseases, according to inspection reports obtained by The AP. The failures, from 2013 to early 2019, ranged from not taking precautionary steps to limit the spread of infections to unsanitary conditions and missed signs that illnesses were passing between residents and employees.

No such data exists for thousands of other group homes for the disabled because they are less regulated. But the Associated Press found those homes have also been hit hard by the virus.

Nearly half of the 2,300 Intermediate Care Facilities with past problems controlling infections were cited multiple times -- some chronically so -- over the course of multiple inspections. In dozens of instances, the problems weren’t corrected by the time regulators showed up for a follow-up visit. At least seven times, the safety lapses were so serious that they placed residents’ health in “immediate jeopardy,” a finding that requires them to make prompt corrections under the threat of a losing government funding.

This 2015 photo provided by the family shows Joe Sullivan, of the Chicago-area, and his parents celebrating his birthday at a restaurant. (Family photo via AP)

Inspection reports analyzed by The Associated Press showed that regulators repeatedly found examples of:

- Staff not washing hands while caring for multiple residents or re-using protective gear like gloves and masks.

- Unclean environments, such as soiled diapers or linens left out, insect infestations, dried body fluids and feces on surfaces of common areas.

- Outbreaks of influenza, staph/MRSA and scabies in a small number of cases.

Other types of group homes aren’t included in the data, but it’s clear that many were also poorly prepared to stop the spread of the virus, The AP found. For example, hundreds of group homes in Massachusetts reported positive cases, as well as the state’s two Intermediate Care Facilities, according to The AP and advocacy groups. Advocates say low pay and difficult working conditions have led to high staff turnover and inadequate training, exacerbated by the pandemic.

Advocates are urging the federal government to do more to protect the disabled in congregate settings. They noted that as the virus spread, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ordered states to provide information to the federal government about COVID-19 infections and deaths in nursing homes. CMS also increased fines and made data about infections in nursing homes available to the public.

But the requirements did not extend to homes for the developmentally disabled, where the overall population is smaller but the virus is still taking a heavy toll.

“The lives of people with disabilities in these settings are equally as at risk -- and equally as worth protecting -- as people in nursing homes,” the Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities said in a May 5 letter to Alex Azar, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHS), which oversees CMS.

Some states had outdated plans and policies to face a pandemic, said Curt Decker, executive director of the National Disability Rights Network. In Georgia, for example, he said the state’s policy provided for protective equipment for nursing homes, but not homes for the disabled. He said staffing levels and training were already “a crisis” across the country even before the coronavirus.

“It was clearly a disaster waiting to happen,” he said.

This 2019 photo provided by the family shows Joe Sullivan, right, of the Chicago-area, with his brother, Neil. When COVID-19 began spreading across the country, Neil prayed it wouldn’t hit Elisabeth Ludeman Developmental Center _ where 346 people live in 40 ranch-style homes spread across a campus that resembles an apartment complex. If it did, he knew his brother and others there would be in danger. (Family photo via AP)

CORONAVIRUS: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

CMS did not respond to The AP’s questions within two weeks and did not say why requirements are different for nursing homes. For days, the agency said it was working on a statement but did not provide one.

“These people are marginalized across the spectrum,” said Christopher Rodriguez, executive director at Disability Rights Louisiana, which monitors the state’s homes for the disabled. “If you have developmental disabilities, you are seen as less than human. You can see it in education, civil rights, employment. And now, you can see it by how they are being treated during the pandemic.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.