ATLANTA – Lawyers for a man set for execution next week are asking Georgia's parole board to spare his life, arguing that newly discovered evidence raises doubts about their client's guilt.

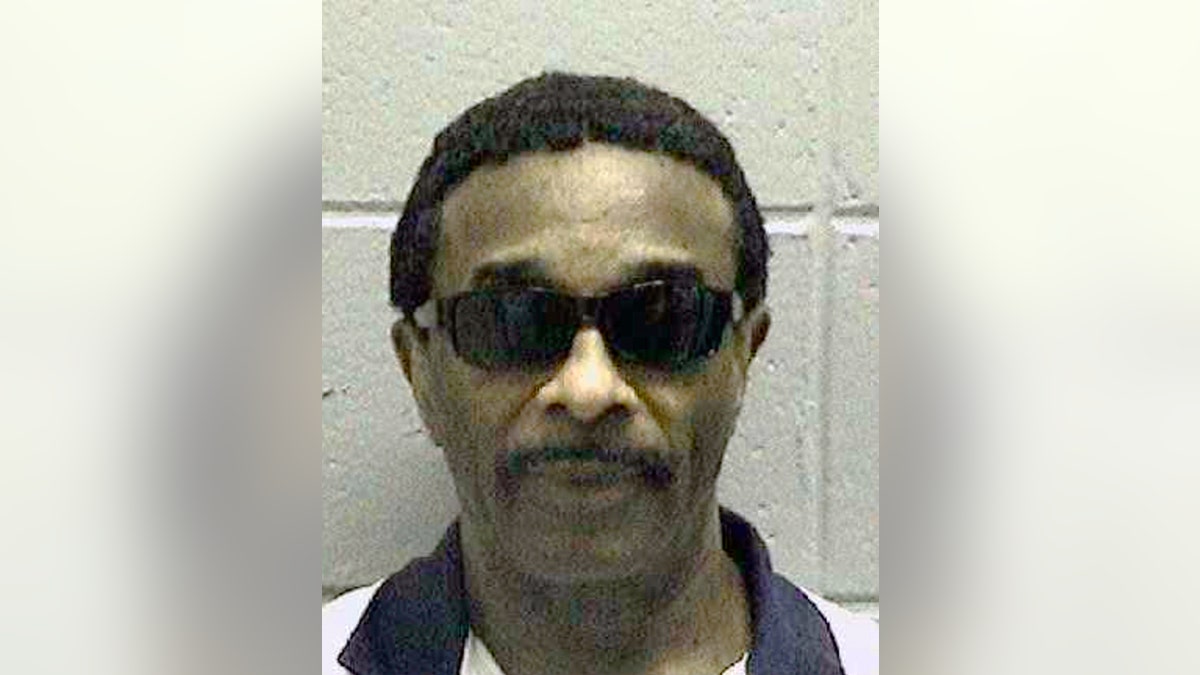

Carlton Gary, who's known as the "stocking strangler," is scheduled to die March 15 by injection of the barbiturate pentobarbital. The 67-year-old inmate was convicted in 1986 on three counts each of malice murder, rape and burglary for the 1977 deaths of 89-year-old Florence Scheible, 69-year-old Martha Thurmond and 74-year-old Kathleen Woodruff.

From September 1977 to April 1978, a string of violent attacks on older women terrified the west Georgia city of Columbus. The women, ranging in age from 59 to 89, were beaten, raped and choked, often with their own stockings. Seven died and two were injured in the attacks.

Prosecutors have consistently said the same man carried out all nine attacks.

Police arrested Gary six years after the last killing, in May 1984. He became a suspect when a gun stolen during a 1977 burglary in the upscale neighborhood where all but one of the victims lived was traced to him.

In a clemency application submitted Wednesday to the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, Gary's lawyers argue evidence that would have helped their client wasn't available to his defense team at trial because the necessary testing methods didn't exist at the time or because prosecutors failed to disclose it.

"We are not talking about questionable recanting witnesses who came forward long after trial, but hard physical evidence of innocence," his lawyers wrote. That evidence would have raised reasonable doubt in the minds of the jurors who convicted him, they contend.

The arguments in the clemency petition have previously been raised in court filings, and lawyers for the state have consistently disputed their validity.

The parole board, which is the only authority in Georgia with the power to commute a death sentence, has scheduled a closed-door clemency hearing for Gary on March 14.

Since the state says the same person carried out all the attacks, excluding him from even one "would prove, under the prosecution's own theory, that Mr. Gary was innocent of all nine attacks," his lawyers wrote.

DNA testing done years after the trial on semen found on clothing worn by one of the women who survived does not match Gary, his lawyers wrote. That's significant, Gary's lawyers assert, because the woman had dramatically identified Gary as her attacker during his trial, and the prosecution relied heavily on her testimony.

The defense also belatedly received a police report in which the woman is reported to have told officers she was asleep at the time of the attack, that her bedroom was dark and she wouldn't be able to identify or describe her attacker, the clemency application says.

Bodily fluid testing done on semen found on Thurmond's body and on stains on Scheible's sheets also likely exclude Gary, his lawyers argue. DNA analysis would have provided further evidence, they wrote, but it couldn't be done because the samples were discovered to have been contaminated at the Georgia Bureau of Investigation crime lab.

A shoeprint found at one of the scenes was not disclosed to the defense until 20 years after his trial and would have cast doubt on his guilt because his size 13-and-a-half foot would not have fit in the size 10 shoe that made the print, the application says.

Additionally, defense experts testified that evidence of a bite mark on one of the victims that was missing for years does not match Gary's teeth, and fingerprint evidence relied upon by the prosecution was problematic.

Authorities have said Gary confessed to participating in the burglaries but said another man committed the rapes and killings. His lawyers say the unrecorded and undocumented statement "fits all the recognized hallmarks of a false confession that never happened."

Lawyers for the state have previously disputed these claims in court filings. They say Gary's claims have repeatedly been rejected by the courts. Furthermore, they've argued, the state now has even more evidence that proves Gary's guilt, and a judge who denied him a new trial found that none of the evidence Gary's lawyers cited would likely have changed the verdict.

Gary would be the first inmate executed by Georgia this year.