Pam Garozzo and her son, Carlos, three weeks before he died from a drug overdose. (Courtesy of Pam Garozzo)

The Chinese government’s recent decision to ban the manufacture and sale of four types of the synthetic drug fentanyl next month came too late for Carlos Castellanos.

The 23-year-old Pennsylvania man had been off drugs for 10 months when he was found dead in a car parked by a train station. Castellanos looked happy and healthy when he walked his mother, Pam Garozzo, down the aisle at her wedding on Dec. 3. But on Dec. 23 Castellanos relapsed, overdosing on a drug apparently laced with fentanyl.

“It took us by total shock,” Garozzo said of her son’s death. “He was very happy, healthy, he had a girlfriend, he had plans to go back to college, he wanted to be an engineer, he was facilitating meetings to help other people in drug recovery. But the drugs are toxic and they’re everywhere.”

China announced Wednesday night that it will ban carfentanil, furanyl fentanyl, acrylfentanyl and valeryl fentanyl from being manufactured there – a move that U.S. officials at the federal and state levels say is significant and likely to be felt in communities across the country.

2015: A Staten Island, N.Y. mother holds an urn filled with the ashes of her son, who died of a drug overdose. (Reuters)

Manufacturers and organized crime groups in China are the source of the bulk of fentanyl that is upending U.S. lives, and killing more than 700 people each year. It is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine. People whose skin accidently has come in contact with it have become addicted.

U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency officials see tighter fentanyl controls by China as a game-changer. When it got tougher about regulating 100 synthetic chemicals in 2015, the global supply of those substances plummeted, some as much as 60 percent, according to the DEA.

This scourge knows no socioeconomic or ethnic or geographic bounds.

“The DEA views China's actions to be four giant steps in the right direction, steps that will ultimately lead to the reduction of numerous overdoses that have occurred throughout the United States, especially the last couple of years,” DEA spokesman Melvin Patterson told Fox News of the new fentanyl controls.

Patterson said that rigorous regulation of fentanyl in China should make it vastly easier for U.S. investigators to trace fentanyl and drugs laced with the deadly substance back to the illicit sources. Until now, China had been an exasperatingly indecipherable key piece of the puzzle in the fight against fentanyl trafficking and catching those aggravating the worst addiction crisis to hit the United States.

While other countries tightened their control over fentanyl, China did not, despite years of urging from the United States.

Dealers discovered in the last two or so years that vast profits could be made by cutting fentanyl into illicit drugs. In fiscal year 2014, U.S. authorities seized just 8.1 pounds of fentanyl. By the first half of last year, they seized 295 pounds, according to Customs and Border Protection data. Overdose rates have been skyrocketing.

Summary

In 2016, the U.S. lost more than 52,000 -- enough to fill a major league baseball stadium -- to drug overdose, 33,000 of which were from opioids.

About 10 years ago, gun-related deaths outnumbered opioid-related death by more than 5-to-1. Today, more people die from opioid-related deaths than from gun homicides and traffic accidents combined.

On on average day, 144 people in the U.S. die from a drug overdose, the majority are from pharmaceutical opioids or heroin or fentanyl.

Every day, nearly 600 people try heroin for the first time.

Source: U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration

“In every community it’s a concern now,” said New Jersey state Assemblyman Declan O’Scanlon, one of the legislature’s most vocal proponents of assertive measures to address the addiction crisis. “I cannot be too dramatic about this. This scourge knows no socioeconomic or ethnic or geographic bounds.”

China’s decision, finally, to do its part to make fentanyl harder to access “is heartening,” O’Scanlon said.

Just days ago, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie signed the toughest law in the country regarding opioid prescriptions and insurance coverage of addiction treatment.

Like many other states, New Jersey has been hard hit by the addiction crisis.

The toll of opioid addiction is being seen by families, police, hospital emergency staff, teenagers and millennials who have attended funerals – sometimes several – for current or former classmates.

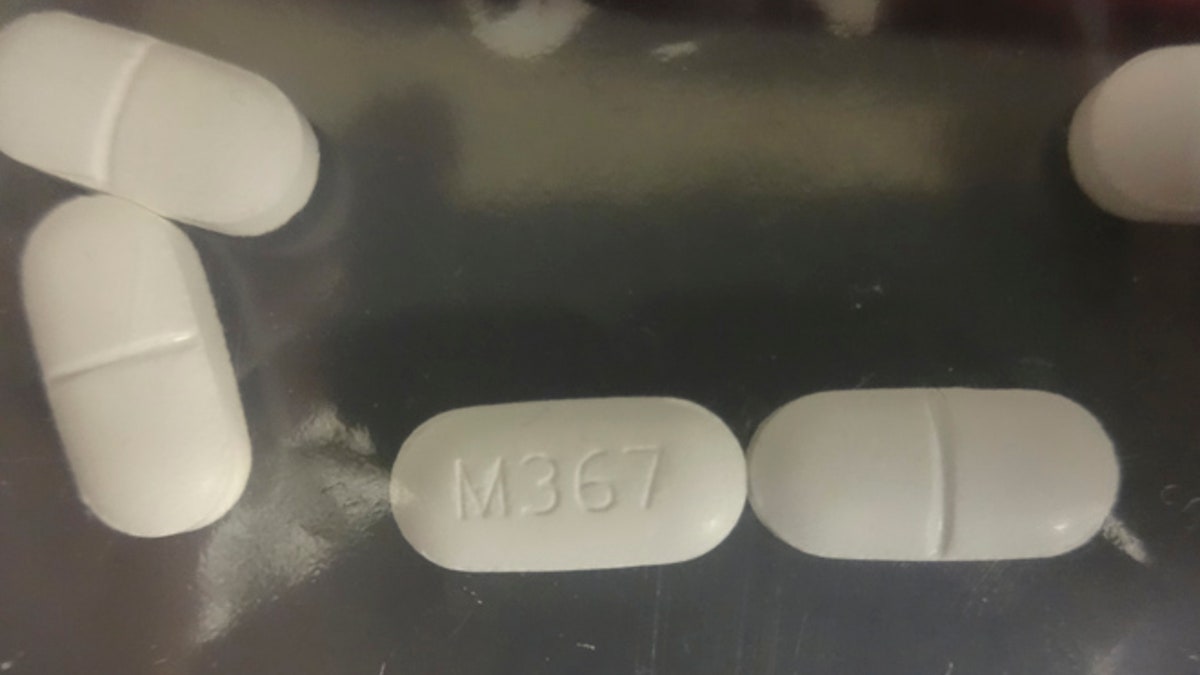

Seized counterfeit hydrocodone tablets in investigation of rash of fentanyl overdoses in northern California in 2016. In two weeks, the area saw 42 overdoses, 10 of them fatal. (Reuters)

Paula DeJohn owns the Silverton Memorial Funeral Home in Toms River, a New Jersey shore community where 40 percent of the population has an annual household income between $75,000 and $200,000.

In the last couple of years, as the opioid addiction and overdose epidemic intensified – to a large extent because of fentanyl -- DeJohn has handled more funerals than she ever has for people who never got to brush gray hair.

“Everything runs down to us,” DeJohn said. “We’ve been seeing a lot of kids, it’s unbelievable. It’s primarily high school kids, but also young people in their 20s and 30s. Before it was rare to see a young person. Now it’s constant.”

In one 10-day stretch last year the bodies of three young people were brought to the Silverton funeral home.

“I have friends affected by this, and kids who are addicted who I saw grow up,” she said. “The parents tried everything to break the cycle.”

New Jersey Attorney General Chris Porrino, a key figure in the state’s war on opioids and whose mission it is to expand treatment for addiction, said he welcomes China’s decision to join the global move toward tightening control over fentanyl.

But he is taking a wait-and-see attitude.

“It’s a big development,” Porrino said of China’s announcement. “We’re optimistic that this will make a difference. Fentanyl takes a bad situation [regarding drug addiction] and makes it so much worse.”

Echoing many experts on the subject, Porrino said he doesn’t understand why China waited until now to do what so many others nations began doing years ago.

“It’s an epidemic and a disease and it’s spreading,” he said.

Which is why the DEA, lawmakers and law enforcers say the solution is multi-pronged and goes beyond cutting off supply.

“Part of the epidemic isn’t about illicit supply,” David Shirk, a global fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told Fox News. “China’s regulations will make illicit production harder to access. For so many people addicted to opium, it starts with legal access to prescription medicines, which [later] is abused.”

“A lot of the problems, at the end of the day, contributing to addiction are social and psychological,” Shirk said, “and the fact that we don’t have a strong support system to help people deal with it.”